Church of The Donald

Never mind Fox. Trump’s most reliable media mouthpiece is now Christian TV.

HENDERSONVILLE, Tenn. — The Music City campus of the Trinity Broadcasting Network is about a half-hour drive from Music City itself, in a placid Nashville suburb on a bend in the Cumberland River where the main road through town is called the Johnny Cash Parkway. TBN, America’s largest Christian television network, acquired the complex in 1994 after the death of country singer Conway Twitty, who had operated it as a sprawling tourist attraction he called Twitty City. Last year, TBN renovated Twitty’s personal auditorium, leveling the floor, adding large neon signs and a faux-brick backdrop under the original Corinthian columns. The resulting TV set looks like an urban streetscape framed by a Greek temple.

On a February night, in his large office just above the auditorium, the network’s biggest star is making last-minute plans for what’s shaping up to be a busy evening. First, Mike Huckabee fields some logistics for dinner at his nearby condo, where he will host three couples who won the privilege in a charity auction. He takes a call from the actor Jon Voight, who tells Huckabee he is free to do an interview about Israel. (Huckabee leaves the next day for Jerusalem, where TBN opened another studio a few years ago.) He checks with one of his producers about an old “Laugh-In” clip Huckabee had requested. “We aren’t paying $6,500 for it, good gosh!” he laughs when he hears the cost of the snippet. “Did they point a gun at your head and wear a ski mask when you asked that?” (They decide not to use it.)

Two hours later, Huckabee walks onto a stage in front of more than 200 people and kicks off a taping of his hourlong cable show. For nearly all of its 45-year history, Trinity’s programming had been strictly religious, a mix of evangelical preachers, gospel music and a flagship talk show called “Praise the Lord” (now just “Praise”). But Huckabee’s show is saturated with politics. The former two-term governor of Arkansas and one-time Iowa caucus winner opens with a disquisition on the Fourth Amendment (“Our system is designed to make sure the government is your servant”) leading into a pre-taped interview with Senator Rand Paul. It’s followed by an appearance by Kayleigh McEnany, the Republican National Committee spokeswoman and a frequent campaign surrogate for Donald Trump. The crowd roars with laughter when Huckabee promises he won’t go on for as long as Nancy Pelosi, a reference to her recent filibuster-style speech on the House floor. “Can you imagine Nancy Pelosi for eight hours?” he asks, chuckling. “NO!” the audience shouts back.

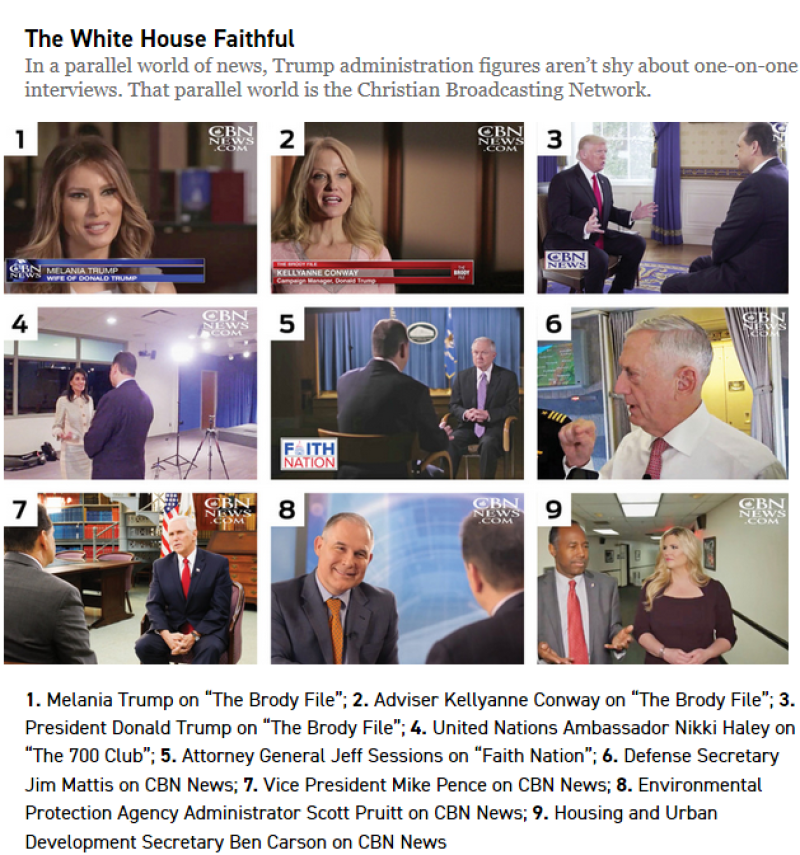

Donald Trump has forged a particularly tight marriage of convenience with

Pat Robertson’s (pictured) Christian Broadcasting Network (CBN),

which since early in the 2016 campaign has offered consistent

friendly coverage and been granted remarkable access in return.

Trump personally has appeared 11 times on CBN since his campaign began;

in 2017 alone, he gave more interviews to CBN than to CNN, ABC or CBS.

Steve Helber/AP

When “Huckabee” made its debut on TBN last fall, it immediately became the network’s highest-rated show, with more than a million viewers for a typical episode. Unlike every other show the network has produced, it is overtly political and squarely focused on current events. It has a variety component, with musical guests and comedians, and Huckabee occasionally breaks out his own bass guitar on stage. But in its six months on the air, Huckabee has also interviewed Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Trump-defending Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, anti-abortion activist Serrin Foster and former Senator Joe Lieberman. The very first guest on his very first show, last October, was President Trump.

A generation ago—even a few years ago—this would have been unthinkable. Christian TV was largely the province of preachers, musicians, faith healers and a series of televangelism scandals. Politicians were leery of getting too close. To establishment evangelicals, not to mention the rest of America, Christian TV was hokey at best, and disreputable at worst.

But in the past two years, largely out of view of the coastal media and the Washington establishment, a transformation has taken place. As Christian networks have become more comfortable with politics, the Trump administration has turned them into a new pipeline for its message. Trump has forged a particularly tight marriage of convenience with Pat Robertson’s Christian Broadcasting Network, which since early in the 2016 campaign has offered consistent friendly coverage and been granted remarkable access in return. Trump personally has appeared 11 times on CBN since his campaign began; in 2017 alone, he gave more interviews to CBN than to CNN, ABC or CBS. Trump’s Cabinet members, staffers and surrogates also appear regularly. TBN has embraced politics more gingerly—it is still not a news-gathering organization—but Trump has made inroads there, too, starting with his kickoff interview on “Huckabee.”

The benefits are mutual. For the networks, having White House officials regularly on screen gives new legitimacy to media organizations that have long felt looked down upon. CBN has belonged to the White House press corps for decades and occupied a seat in the White House briefing room since the Obama era. But its status has risen dramatically during the Trump presidency, when press secretary Sean Spicer gave questions to CBN reporters three times in the first two weeks of the term. During a joint news conference with Netanyahu, Trump himself picked CBN’s chief political correspondent, David Brody, to ask the first question. “The Trump administration has given CBN News the opportunity to be recognized in places a Christian news organization normally wouldn’t,” CBN vice president and news director Rob Allman wrote in an email.

For the White House, the relationship is arguably even more useful. Christian broadcasters offer an unmediated channel to the living rooms of a remarkably wide swath of American believers, an audience more politically and racially diverse than you might expect. TBN alone has more local stations to its name than Fox or the three major networks. “It’s about as direct a route as you can go,” says Michael Wear, a former Obama White House and campaign staffer who has appeared on CBN. They offer Trump officials a softball treatment available in few other venues. Huckabee’s own daughter, after all, is the president’s press secretary—a relationship that would disqualify him as an interviewer on most networks. One of Huckabee’s questions to the president was about the first lady, and whether it bothered the president that his wife “has fantastic approval ratings, soaring above anybody else in the entire city of Washington.”

This dance between administration politics and televised religion is new, and is built on a connection between Trump’s message and the Christian TV worldview that runs deeper than it might first appear. It also offers a different kind of answer to the puzzle of why an impious man who can barely manage to pay lip service to actual Christian belief earned a higher percentage of the white evangelical vote than predecessors including Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush—and why, if anything, his bond with those voters appears to be growing stronger.

***

Evangelists have been a fixture of television since the 1950s, and there’s a reason politicians stayed away for so long. Almost from the start, TV preachers carried a unique whiff of tawdriness. There were the preferences for gaudy sets, big hair and absurd stunts, for one. Oklahoma televangelist Oral Roberts once told viewers that unless he received an extra $8 million by the next month, he would die. (The ensuing wave of donations spared him.) Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker opened their own theme park in the 1970s, and TBN, with its own roster of flashy preachers, still maintains its Holy Land Experience park in Orlando, Florida. Then there were the waves of legal disgrace. The “Gospelgate” scandals of the 1980s, implicating big-ticket televangelist Jimmy Swaggart and the Bakkers with a series of sexual and financial misdeeds, seemed to permanently tar the whole enterprise.

Not all Christian television is televangelism, and not all televangelists are corrupt or even tacky. But American presidents have nonetheless mostly steered clear, preferring to select their religious advisers from more sober ranks of pastors and writers. (Billy Graham, spiritual adviser to many presidents, preached on television but had roots and connections far beyond the airwaves.) Presidents occasionally granted interviews, especially with the powerful Robertson, founder of CBN, with whom President Reagan sat down on the network’s “The 700 Club” in 1985—but they have done so carefully and rarely.

Trump had none of that caution. He started showing up on Christian TV years ago, giving his first interview to Brody back in 2011, when he was toying with a run for president that no mainstream network took seriously. Trump discussed his “conversion” to opposing abortion, his respect for the Bible (“THE book”) and his churchgoing habits (“I go as much as I can”). Most Republican candidates make occasional stops by CBN to woo conservative Christians. But Trump seemed to take a real shine to Brody, and he must have known he would need to put in overtime to bolster his credibility with religious voters. As his 2016 run gained momentum, a steady stream of staffers and surrogates, including Kellyanne Conway, former Representative Michele Bachmann and televangelist Paula White, appeared on the network to vouch for Trump’s Christian credentials. White told Brody in June 2016 that Trump had first discovered her ministry by watching Christian broadcasting more than a decade before. “Mr. Trump has always been a huge fan,” she said. “He’d always watch Christian television.”

Whether or not that was true, Trump seemed to sense early on that the Christian television audience would be receptive to his campaign theme of a kind of resentful nostalgia for an imagined idyllic past. When I interviewed Brody last year for a profile, he said Trump shared with older evangelicals a longing for “1950s America,” characterized by patriotism, prayer in school and an absence of political correctness (though he took pains to clarify that the ’50s were not a good era for “race relations”). As Huckabee puts it on one of his promos on TBN, “If you like baseball, apple pie and you love your mom, I’ve got just the show for you.”

But if Trump detected a cultural affinity with viewers of Christian television, he was also capitalizing on a deliberate turn that the medium was already taking. On TBN, “Huckabee” is part of a change under the leadership of Matt Crouch, who took over recently from his father, Paul, who founded the network back in 1973. The talk show is the network’s most obvious nod to politics, but in the past few years it has also added a newsmagazine show called “The Watchman,” focused on “gathering threats to America’s and Israel’s security”—it’s hard to overstate Christian TV’s interest in Israel—and started airing “Somebody’s Gotta Do It,” in which blue-collar conservative Mike Rowe visits “hardworking Americans” on the job. (Rowe’s show originally aired on CNN; TBN recut the episodes to include scenes like family prayers and snipped out mild cursing.) This is, in part, an effort to reach a new audience of millennials who aren’t as interested in watching sermons on TV. “We’ve got to get beyond the church, beyond the pews,” Colby May, a TBN board member, said of the network’s new direction. May says TBN isn’t trying to emphasize politics per se, but to be seen as more relevant. Huckabee’s interview with Trump “was an exciting and different kind of guest for Christian television,” he says.

CBN, for its part, had been in the news business since the 1970s, when the network opened a bureau in Washington, and “The 700 Club” transformed from a variety show into its current newsmagazine format. Robertson relishes his role as a kind of ward heeler of the Christian conservative vote, and candidates courting that vote would make obligatory campaign stops on CBN. But Robertson’s own pronouncements on current events seemed enough to keep mainstream politicians at arm’s length: Since the peak of his influence in the 1980s, he has become better known for dire predictions based on divine revelation, his notorious linkage of Hurricane Katrina to American abortion policy and his repeated insistence that Islam is less a religion than a dangerous political system.

If that last point sounds like something you might have heard at a Trump campaign rally, that begins to get at the affinity between Trumpworld and this particular set of TV viewers. In retrospect, it’s possible to see Robertson as a kind of elder statesman of the exact kind of “politically incorrect” conservative populism that Trump’s campaign rhetoric tapped into so naturally. A viewer who had stuck with Robertson through all that wasn’t likely to be put off by a candidate who took potshots at Mexicans and Muslims.

By the time Trump arrived on the political scene, it almost didn’t matter that he wasn’t much of a Christian, or tended to mangle the names of the books of the Bible. This audience recognized him as a kindred spirit in everything but religion. His hair-sprayed reality-TV persona—to say nothing of the bluster and the heroic monologues—aren’t that far from the preaching style that has prospered on cable evangelism. His family’s pastor when he was a child wasn’t the minister of the local Presbyterian church, but celebrity success guru Norman Vincent Peale, who had a long-running radio show called “The Art of Living.” Trump ran his campaign events more like tent revivals than policy symposia. And his books and TV persona dovetailed surprisingly well with the “prosperity gospel” preaching that thrives on Christian TV, the relatively new American theology in which material wealth is seen not only as a reward for good behavior, but a kind of endorsement by God.

***

Today, Christian broadcasters have rewarded Trump not just with airtime for his surrogates, but with uncritical, often defensive coverage of his administration. Appearing as a guest on “The Jim Bakker Show” soon after the racial violence in Charlottesville, Virginia, last summer, Paula White compared Trump to the biblical queen Esther, and told viewers that opposing the president meant “fighting against the hand of God.” CBN’s Brody this year published a hagiographic “spiritual biography” of the president, The Faith of Donald J. Trump, in which he argues that Trump is on a “spiritual voyage” that has landed him surrounded by believers in the Oval Office. The president obligingly sat down for an interview for the book and later promoted it on Twitter as “a very interesting read.”

To watch an appearance by a Trump official on “The 700 Club,” or “Faith Nation,” the Washington-based political show hosted by Brody and Jenna Browder that debuted last summer, is to enter a softer precinct of the news universe, one in which officials are treated gently and allowed to air out their views with help, not challenge, from the hosts. When Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney appeared on CBN days after the brief government shutdown in January, he discussed policy issues including immigration and the possibility of passing a spending bill. When Brody asked him about what he would say to Hispanic Christians worried about deportation, Mulvaney reassured them that the president “wants to figure out a way for the DACA folks to stay.” Brody didn’t push him with a follow-up. In December, Vice President Mike Pence went on Brody’s show in part just to reassure evangelicals that Trump is on their team. “The president is a believer, and so am I,” Pence told Brody. “The American people, I think, can be encouraged to know that in President Donald Trump, they have a leader who embraces and respects and appreciates the role of faith and the importance of religion in the lives of our families, in communities in our nation, and he always will.”

It’s not just a “trust me” argument: Trump has actually delivered the goods in Washington, especially for this particular strain of evangelicals. And he has brought more televangelists and Christian broadcasters into his inner circle than any president before him. White, arguably his closest spiritual adviser, hosted a show that aired on TBN and BET for years. His lawyer, Jay Sekulow, has his own daily call-in radio show on a Christian network. Trump’s faith advisory board, announced during the campaign, included many members drawn from the world of television ministry, including Ken and Gloria Copeland, who have headed a daily program since 1989; Tony Suarez, who hosts a talk show on TBN’s Hispanic-oriented network; Jentezen Franklin and Robert Jeffress, whose sermons air as their own programs on TBN; and Mark Burns, who founded the web-based NOW Network. Johnnie Moore, another advisory board member, is a communications consultant who has worked with clients including CBN. “If you look at his evangelical advisory council, it’s people with media connections, more than broad church-based connections,” Robert Jones, CEO of the Public Religion Research Institute, says. “That’s a weird slice of the evangelical world.”

Closer to Trump’s inner circle, the list of friendly faces continues. “This is an evangelical Cabinet,” says Jerry Johnson, president of the National Religious Broadcasters. “You’re looking at name-brand conservative evangelicals that are very comfortable talking to Christian media types.” Jeff Sessions, Scott Pruitt, Rick Perry, Ben Carson and Pence, all evangelical Christians who talk frequently about faith, are among those who have appeared on CBN since Trump took office. And CBN has closely covered what it calls a “spiritual awakening” at the White House, including Oval Office prayers and a weekly Bible study involving many Cabinet members, at one point including Betsy DeVos and the now-departed Tom Price.

Pence, who himself hosted a conservative talk-radio show and a television show in Indiana in the 1990s, has been a particularly cheerful booster of the work of Christian broadcasters. Speaking at the 75th annual meeting of the National Religious Broadcasters in February, Pence praised its membership’s work. “Your ministry, your message, your values are needed now more than ever before,” he told the crowd in Nashville. “Every day, every hour, you speak strength to the heart of the American people. You shape our country.” (Christian radio is a different business with a somewhat different audience, but it has proved similarly attractive to Trump. Salem Media Group, the largest Christian radio broadcasting platform in the country, spent a day at the White House last summer, hosting a special broadcast with the theme “Made in America.”)

***

The audience Christian TV is delivering has a surprising kind of political traction, especially if you lost track of Christian broadcasting after the scandals of the 1980s. “Decline is such an easy narrative,” says Mark Ward, editor of the 2015 book The Electronic Church in the Digital Age. “What really happened is [televangelism] went underground.”

Newer TV preachers might not be national celebrities with the name recognition of Oral Roberts and Jimmy Swaggart, but they remain influential. Reliable data on the sector are hard to come by, but a 2005 survey by an evangelical pollster found that 45 percent of American adults watched Christian television on a monthly basis, just as many as in 1992. “It’s one of these stories that has just gone completely under the radar,” Ward says. “Even though it doesn’t have the same profile it had, it’s still a very decisive arbiter of the evangelical subculture.”

TBN in particular has quietly become a major player, in part by capitalizing on the switch to digital TV two decades ago. When the Federal Communications Commission declared in 1996 that all television stations had to convert to digital broadcasting within a decade, the network’s founders, Paul and Jan Crouch, snapped up many local Christian stations that couldn’t afford the conversion. As a result, TBN is now the third-largest television group in the country, with access to 100 million households and more local television stations to its name than Fox or the three major networks. Its largest rival, Texas-based Daystar, also claims access to 100 million households, and carries many of the same programs. (CBN is no longer technically a network but a production company with a series of syndicated programs that air on stations owned by others, including TBN.)

The networks haven’t escaped the whiff of scandal, particularly TBN, which was hit by another series of negative headlines just within the past few years, including lawsuits and a family feud that left Matt Crouch in charge. Last summer, a California jury awarded Paul and Jan Crouch’s granddaughter $2 million after she said she had been sexually abused by a TBN employee. There are also questions about its financial health: When the Orange County Register reviewed the company’s tax filings in 2016, it found a revenue drop from $207 million in 2006 to $121.5 million in 2014. About five years ago, TBN banished its fundraising “praise-a-thons,” which relied largely on small donations from low-income viewers, and now relies more on underwriting and traditional fundraising efforts. Last year, the network sold at least two significant properties in Southern California, including its gaudy headquarters in Costa Mesa.

But viewers still appear to be loyal, and those viewers aren’t who you might think. Both TBN and CBN say their audiences are split almost evenly between Democrats and Republicans. This can likely be chalked up to another fact that might surprise people outside the evangelical bubble: their audiences’ racial diversity. Charismatic and Pentecostal preaching, and the related health-and-wealth “prosperity gospel,” are strong traditions within the black community. Popular black pastors including Creflo Dollar, Tony Evans and TD Jakes have all preached regularly over the years on TBN, Daystar, and other Christian networks. Paula White is the pastor of a largely black church. And CBN’s roster of reporters, hosts and regular guests is arguably more racially diverse than those of many cable news networks.

Wear, the faith outreach director for the 2012 Obama campaign, believes the racial diversity of Christian broadcasting has helped inoculate Trump against charges of racism among his white evangelical voters. CBN and TBN’s on-air diversity “is a significant reason that much of Trump’s base doesn’t take accusations of racism seriously,” he says.

In October, TBN aired a special on the American church’s role in racial reconciliation, hosted by pastor Samuel Rodriguez, who prayed at Trump’s inauguration. The year before, Rodriguez appeared on CBN to assure viewers that Trump is not a racist. In an interview taped for “Huckabee” in February, Harry Jackson, a black pastor in Maryland who has frequently defended Trump, told Huckabee the same thing.

For white evangelicals, who voted for Trump overwhelmingly and still approve of his job performance, the approach seems to be working. The networks continually polish Trump’s reputation, and perhaps more importantly, he’s talking to them. “Evangelicals, going back to the time of the Scopes trial, have always been sensitive to being seen as pariahs,” Mark Ward says. “You can get a lot of credibility with evangelicals if you simply make them feel like they matter, if you appear on their TV shows and send your administration to appear on their TV shows.”

In a fundamental way, TV people are Trump’s people. “Trump appreciates people who can communicate in an attention-grabbing way,” says Wear, author of the 2017 book Reclaiming Hope: Lessons Learned in the Obama White House About the Future of Faith in America. “I don’t think Trump would be drawn to a preacher who breaks down five chapters of Ephesians and lays out the Greek and Aramaic.”

Trump has always had a particular genius for circumventing normal channels, and he seems to understand the power of Christian television as a medium for directly reaching an important and particularly loyal segment of his base. When Pat Robertson interviewed him last summer, in a period in which Trump had granted no other non-Fox interviews for months, the president put it succinctly. “As long as my people understand,” he told Robertson. “That’s why I do interviews with you. You have a tremendous audience. You have people that I love.”

Extract from the Original article by Ruth Graham , in Politico Magazine .

Know thine enemy...

"To watch an appearance by a Trump official on “The 700 Club,” or “Faith Nation,” the Washington-based political show hosted by Brody and Jenna Browder that debuted last summer, is to enter a softer precinct of the news universe, one in which officials are treated gently and allowed to air out their views with help, not challenge, from the hosts."

I don't think they should be called "hosts" anymore, they are nothing but fluffers.

This is another aspect of violating the spirit of the establishment clause. Any elected official showing up on religious TV is effectively making an official endorsement of that religion and their views as much as the religion is giving an endorsement of the elected official. They should all lose their tax exempt status if they feature and promote political candidates.

Umm... ethics? Trump administration?

Trump's base largely consists of evangelicals. It is so extreme in terms of the numbers that without the evangelicals his popularity would be below 20%.

It's funny to observe this and then realize that Obama was accused of catering to blacks, who represent about 1/2 the number of people in the US that evangelical Christians do.

The reach of The Deceiver is long. His Shadow is longer.

Deceit, fear and malice is the 'new faith.'

Why do I have the feeling that president trump will be letting a lot of the faithful down very soon ?

You cant walk far in darkness.

In The Shadow of Lucifer the light of darkness will show the way for the afraid.

Great line! Must be said with a cavernous voice...

Although I doubt the faithful expected to follow that light went they got in line..

The 'so called faithful' have no faith.

They BELIEVE in Trump.