Reagan, Deregulation and America’s Exceptional Rise in Health Care Costs

Some readers and experts have responded to a recent article by pointing out that the 1980s increase in U.S. health costs coincided with a broad push toward deregulation.

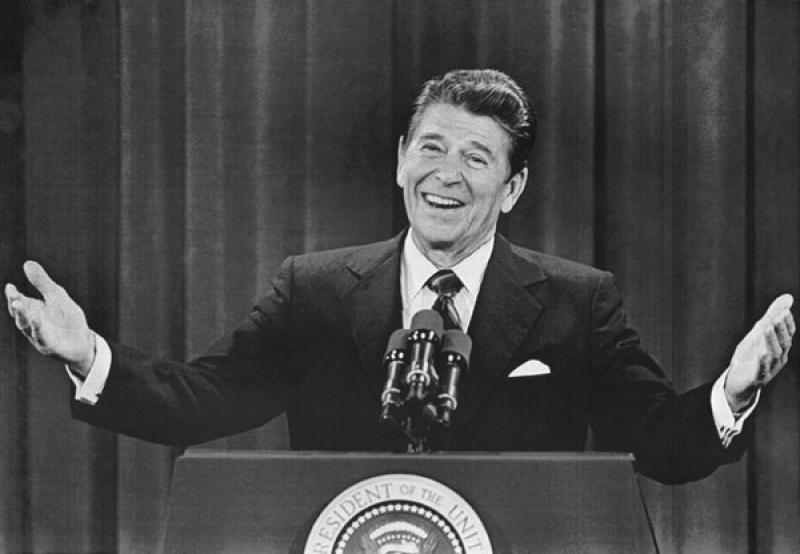

Was the cheerful deregulator to blame for rising health care costs?

A lot of readers seemed to think so.

D. Gorton/The New York Times

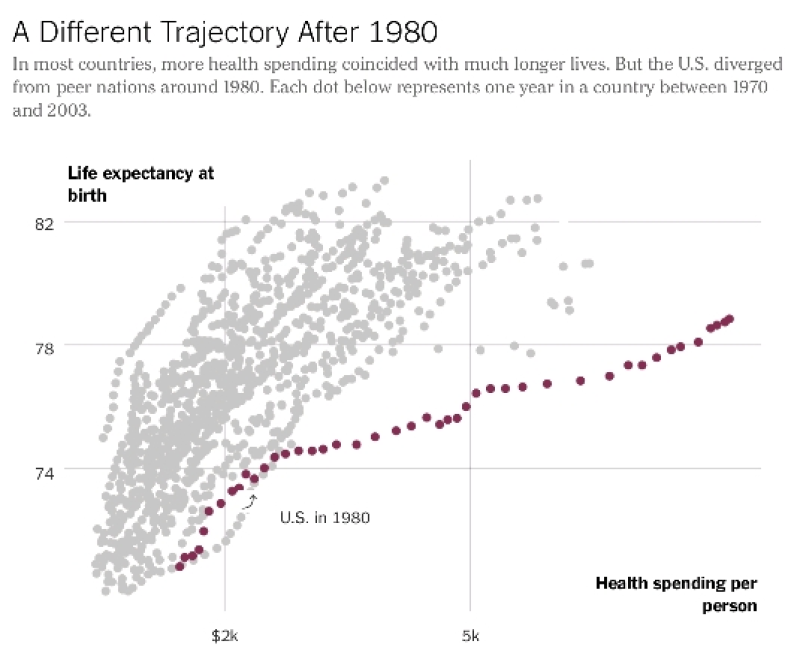

Why did American health care costs start skyrocketing compared with those of other advanced nations starting in the early 1980s? At the same time this was happening, American longevity gains were failing to keep up with peer countries.

In addressing these twin mysteries in a recent article, experts suggested two main reasons: The United States didn’t impose the same types of government cost controls on health care that other nations did, and we invested less in social programs that also promote health.

Many readers have since commented that it had to do with the Reagan-era zeitgeist, or increasing obesity. In the intervening weeks, I have spoken with many more health care experts — about their ideas as well as those of readers — and several, while believing the article essentially covered the answers, offered intriguing new observations.

The 1980s divergence in health costs, some readers and experts observed, coincided with a broad push toward deregulation. Gary Gaumer, an associate professor at Simmons College School of Business, pointed to changes in how hospitals and doctors were paid. Before the early 1980s, payments by Medicare and other insurers were tied to costs. If it cost a hospital, say, $5,000 for a patient’s surgery, that’s what the hospital was paid, plus a bit more for reasonable profit.

But then payers (private insurers and government health care programs like Medicare) began to shift financial risk to providers like hospitals and doctors. It started with a law that began affecting most hospitals in 1983, changing how Medicare paid hospitals to a fixed price per visit, regardless of the actual costs. This approach later spread to other Medicare services and other payers, including private insurers. If providers could get costs down, they made money. If they couldn’t, they lost money.

“Hospitals and other providers began to behave more like businesses,” Mr. Gaumer said. “And the culture of health care delivery began to change.” To lessen risk, hospitals sought revenue at every turn, starting new programs and offering new services — such as providing new outpatient services that previously involved longer hospital stays. Health care organizations became more concerned with growing in scale to absorb the higher level of risk, which helped push health care spending ever higher.

Though shifting more responsibility to the investor-owned private sector seemed to backfire as a cost-control measure, it was consistent with broader deregulation in the 1980s. “We need to see the medical sector as part of the broader gestalt of American society at the time,” said John McDonough, professor of Public Health Practice at the Harvard Chan School of Public Health. President Carter was “obsessed with broad public and private health care cost control, and Reagan abandoned that, with the exception of Medicare,” he said.

The 1980s deregulatory agenda was evident in states as well. Many abandoned health care price and capital investment controls. Managed care — in the form of health maintenance organizations — was the free-market replacement to government regulations. Investor-owned, shareholder-driven, for-profit companies became common in health care for the first time. They focused on revenue and profit maximization, not cost control. “‘Greed is good’ was more than a catchy movie line — it was the Me Decade’s dominant theory,” Professor McDonough said. “No other advanced democracy embraced deregulated health care markets in the way that the U.S. did. It swept through health care as it did every other part of the U.S. economy.”

Further explanations for why the nation fell behind in health care outcomes, starting in the 1980s, are harder to come by. Mr. McDonough pointed to the Federal Trade Commission’s 1978 decision to allow direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs. And the first signs of the obesity epidemic began to appear in this decade, but not enough to explain that decade’s remarkable cost explosion.

Stuart Butler, a senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution, added that underfunding of social services relative to medical care probably played a significant role in both health care spending and outcomes. “I’d like to see more experimentation with investments in nonmedical sectors we know also affect health,” he said, “but we’ll need to track these carefully to find what actually pays off.”

These include housing and education, for example. Gail Wilensky, senior fellow at Project HOPE, an international health foundation, and former director of the Medicare and Medicaid programs under President George H.W. Bush, agreed that the United States spends too much on health care and too little on other social services. Firearms and illicit drugs also contribute to early deaths. However, she pointed to one hopeful example. “The U.S. was unusually successful in smoking cessation, relative to other countries,” she said. “If we could replicate that success in other areas, like obesity reduction, we might close the gap in health care outcomes.”

She said there are other hopeful lessons from history. American health spending pulled away from that of other countries over the decades in large part because of an expansion of programs like Medicare and Medicaid, without the kind of brakes on prices and technology adoption that other countries put in place.

But health spending growth relative to G.D.P. held steady in the 1990s. “That’s partly due to a strong economy,” she said. “But we also put some brakes on Medicare in that decade. In addition, managed care slowed growth in the private sector.” If we did it then, we could do it again, she added.

Austin Frakt is director of the Partnered Evidence-Based Policy Resource Center at the V.A. Boston Healthcare System; associate professor with Boston University’s School of Public Health; and adjunct associate professor with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. He blogs at The Incidental Economist, and you can follow him on Twitter. @afrakt

Did anyone imagine that the healthcare problem was gone?