A sign on scrubland marks one of America's largest slave uprisings. Is this how to remember black heroes?

The Stono rebellion of 1739 was the biggest slave rebellion in Britain’s North American colonies but it is barely commemorated – unlike Confederate leaders...

The slaves met on a Sunday morning, close to the Stono river. Plantation owners tended to go to church on Sundays, and would leave them unattended.

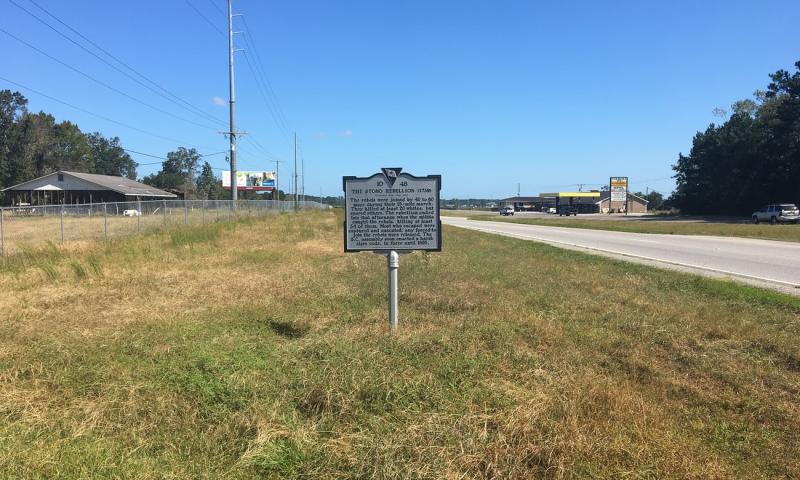

The Stono rebellion sign on a lonely stretch of US Highway 17 in South Carolina.

Adam Gabbatt

A man named Jemmy had gathered them together. Described in reports as an “Angolan” who could read and write, Jemmy had talked the men through his plan the night before.

There were about 20 men in total. They marched to Hutchenson’s Store, 14 miles west of Charleston, South Carolina, and killed two white men. They then loaded up on pistols and gunpowder, and headed south.

Jemmy was leading them towards the then-Spanish territory of Florida, where he had heard slaves could live as free men.

The men marched from the store to a house belonging to a white man named Godfrey. They burned the house to the ground and killed Godfrey, his wife, and his son and daughter.

When the slaves arrived at the home of a man called Lemy they killed him, his wife, and their child. They did spare a man named Wallace, who owned a tavern. He was considered a kind slave owner. But every other home they passed they torched.

It was 9 September 1739, and Jemmy was leading what became known as the Stono rebellion – one of the largest slave uprisings in what was then the North American colonies.

The men would not make it to Florida. They wouldn’t even come close.

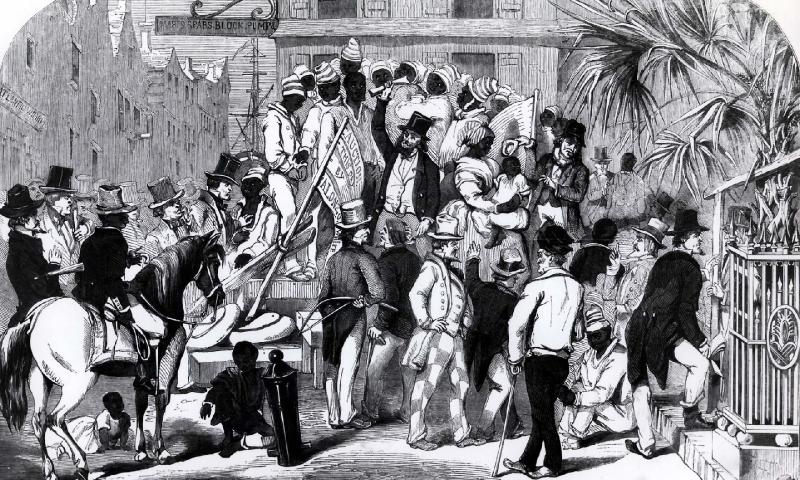

In the 1700s, and on through the 1800s, Charleston was one of the most prominent hubs for the slave trade in North America. At one point 35-40% of slaves entered the US through the city, and it served as a base for trading slaves once they had arrived.

A white man sells black slaves at a sale in Charleston, South Carolina.

At one point 35-40% of slaves entered the US through the city.

Popperfoto/PPP

But walk around Charleston today and the most visible monuments and memorials are not to people like Jemmy and his Stono rebels. The major monuments are to the Confederate leaders who declared their secession from the United States and fought a war over their right to own slaves.

The same is true for cities and states across the country. There are more than 700 monuments to the Confederacy in the US, the majority in the south. Including park and school names, street and bridge names and public holidays, the Southern Poverty Law Center says there are more than 1,500 “symbols of the Confederacy” in public spaces across the country.

There are signs recently that times are changing. Statues of Confederate leaders like Robert E Lee and Jefferson Davis have been removed in New Orleans and Baltimore, with other cities exploring how to take down similar structures.

In 2015, after Dylann Roof killed nine black churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina, finally removed the Confederate flag from the statehouse grounds.

But the fight to erect monuments and memorials to those enslaved – or who fought enslavement – has proved just as difficult as the battle to remove those Confederate symbols.

***

As Jemmy and his group made their way south-west, more slaves joined the Stono rebellion. Their number had swelled to about 100 men before they were spotted, by chance, by South Carolina’s lieutenant governor, William Bull.

Bull rounded up a militia, and they confronted the slaves in the middle of a field near the Edisto river, a winding stretch of water that meets the Atlantic Ocean 50 miles north of the South Carolina-Georgia border. A battle ensued.

Accounts from the time say the slaves fought bravely, but they were outnumbered and their opponents were better armed. The majority of the rebels were slaughtered. Some were taken back to plantations and returned to slavery. About 30 escaped, but were later rounded up and killed.

The plantation owners mounted some of the slaves’ heads on sticks along the main road, as a warning to others.

Jemmy and his men had made it just 15 miles.

There were uprisings over the next two years, although historians are divided on how much they were inspired by Stono. None were on the same scale, and none were successful.

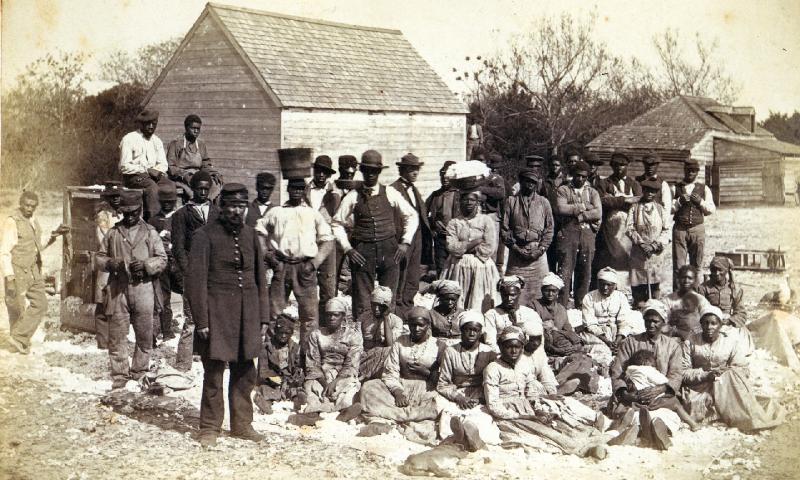

Slavery continued in the North American colonies, and continued when the US became an independent country in 1776. It would be 1865 – more than 120 years after the uprising in Stono – before the 13th amendment to the constitution was ratified and slave ownership was finally made illegal.

Slaves of the Confederate general Thomas F Drayton at Magnolia plantation, Hilton Head, South Carolina,

in 1862, a few miles south-west of where the Stono rebellion was crushed more than a century earlier.

UniversalImagesGroup/Getty Images

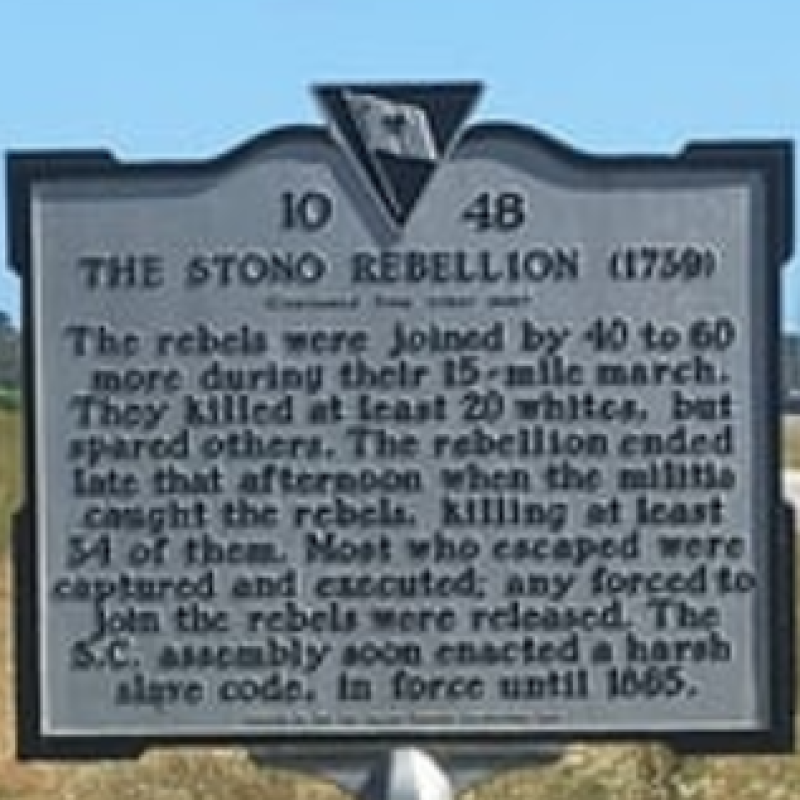

Today the only marker of the failed rebellion is a small sign by the side of US Highway 17, just past the Stono river.

It is not easy to spot. Cars and trucks rumble through this part of South Carolina at 60mph, crossing the marshy expanse of the Stono river before reaching the small town of Rantowles.

The sign is on a grass verge, opposite a gas station and underneath an advertisement billboard currently promoting a Chevrolet and Ford car dealership. There is a corrugated metal building behind it which sells arcade games and pinball machines.

There is no layby to pull into, no place to stop. Even with an idea of where the sign was, I flashed past it before I’d seen it. It took a screech of the brakes and a hard right turn to pull into the arcade store car park and take a closer look.

The marker was erected in 2006 by the Sea Island Farmers Cooperative, and looked as if it has been forgotten in the 11 years since then.

The white background was streaked with dirt. The paint of the small black lettering, which gives a pithy summary of the rebellion, was flaking, and the black border was faded and cracked.

It was hard not to think of the contrast with the gleaming Confederate memorials which loom over streets in downtown Charleston.

On a sunny Wednesday at the end of September the grass at the base of the signpost was long and scorched. Wading through it, I could finally read the 50-word tribute to the enslaved men who had made their bid for freedom.

“The Stono Rebellion, the largest slave insurrection in British North America, began nearby on September 9, 1739,” it reads.

“About 20 Africans raided a store near Wallace Creek, a branch of the Stono River. Taking guns and other weapons, they killed two shopkeepers.

“The rebels marched south toward promised freedom in Spanish Florida, waving flags, beating drums, and shouting ‘Liberty!’”

The Denmark Vesey monument in Hampton Park in Charleston, South Carolina.

Vesey attempted to lead a slave rebellion.

The Washington Post/Getty Images

The largest rebellion of the time may have been doomed, but over the next 100 years more men sought their own version of liberty. Eighty-three years after Jemmy and his men attempted their revolt, Denmark Vesey, a former slave himself, was planning his own large-scale Charleston rebellion.

Around 1800, when he was in his early 30s, Vesey had won $1,500 in a cash lottery. He used some of the money to buy his freedom from his owner, and hoped to use the rest to secure his wife’s freedom, but her owner refused to sell her.

Over the next 20 years Vesey, who had been born into slavery in the then-Danish colony of St Thomas, built up a carpentry business and became a prominent figure in the emerging African Methodist Episcopal church – the church Dylann Roof would target two centuries later.

Vesey maintained friendships with enslaved men, and became increasingly determined to change the state of affairs in South Carolina.

“He’s a man who by that time period was in his 50s, mid-50s. He’s an old man,” said Curtis Franks, museum curator at the Avery Research Center for African American history and culture in Charleston.

“It was this heightened sense of urgency because of where he was in his life to do what he could do to bring about an end to the institution of slavery.”

In 1821 Vesey and other churchgoers began to plan a revolt. By some accounts thousands of men were prepared to join the cause, both in the city and out into the countryside – even as far as the Stono river where their predecessors had assembled nearly a century earlier.

The men planned to attack an arsenal facility in downtown Charleston on 14 July 1822, seize weapons, then commandeer ships and sail to Haiti, where slaves had overthrown French colonialists two decades earlier. Had they made it, Vesey and his companions would have been able to live freely on the island, a thousand miles south-east.

They didn’t make it.

The plot was exposed days before they were due to strike. After a brief trial Vesey and 34 others were hanged, 38 more were deported.

Franks was part of a group of people who wanted to erect a statue of Vesey in Charleston. He saw it as an important counterpoint to the existing monuments that glorify Confederate politicians and leaders.

The group got the backing of some members of the Charleston city council, which at the time was evenly split between black and white people, and of the city’s mayor.

Nevertheless, it took almost 15 years for Franks and the others to get their memorial to Vesey and his would-be rebellion.

They faced opposition in the press, Franks said, and on talk radio. Opponents vilified Vesey as a terrorist – ignoring the hypocrisy of the memorials to people who initiated a civil war – and one proposed site was blocked after residents protested.

The monument to John C Calhoun in Marion Square in Charleston.

Alamy Stock Photo

The group had wanted the Vesey statue in the downtown area, where tributes to the former US vice-president John C Calhoun, a hardline defender of slavery who referred to it as a “positive good” in an 1837 speech, are unavoidable.

The main street running east to west through downtown is named after Calhoun. That street borders the south of Marion Square, where a giant Calhoun statue glares down at passersby.

“In a sense it could offer a counter to the Calhoun piece,” Franks said. This more visible representation of the darker parts of Charleston’s past would not just honour the history of black Americans, Franks said, but also offer something to the people who travel to the city each year.

“There are black folk throughout the country who are visiting Charleston. And they’ve done their work, they’ve done their reading. And they understand the importance of this physical space to this country, and to the world.

“So they’re coming with great expectations, and they get here and that reading, that preparation doesn’t meet or match what they find when they get here,” Franks said.

“You look around and you see all this other stuff that is Confederate.”

The plan to place the Vesey statue there did not pan out. The city of Charleston does not own the park – it leases it from the Washington light infantry, a military organisation that fought on the Confederate side in the civil war.

It was years before a site was agreed on. Franks’s group did not get their downtown location, but were granted a site in Hampton Park, a couple of miles north.

Franks drove me out to see the statue in September. The monument has Vesey standing on top of a plinth, a Bible in one hand and a bag of carpenter’s tools in the other. He has his back to the open green space of the park, facing instead a paved semi-circle with two benches designed for contemplation.

The tale of the Vesey statue shows how divisive the legacy of slavery remains today.

***

This battle to accurately represent both side of Charleston’s history is not lost on locals. I took a cab from the Vesey statue to downtown, and the driver, Jamal Middleton, was aware of the struggles Franks and others from the Avery center had faced.

“It’s the largest monument to anything that has to do with ending slavery or evolution or freeing slaves,” Middleton said of the Vesey memorial.

“And it’s placed in an area where it would be almost difficult to find unless you know where it is.”

Middleton, who once ran a non-profit called the Greater Charleston Empowerment Corporation, drove me along Calhoun Street to point out some of the memorials.

“I mean look at this thing,” he said as we passed the Calhoun statue. I asked how it felt to drive past a tribute to someone who was so keen to keep black people enslaved.

“It’s almost reminiscent of how I would envision a slave would have felt if they were walking down the street and someone’s spit on them. Yeah. Literally that’s how I feel. It is disgusting,” Middleton said.

In Charleston and elsewhere the attempt to properly remember the horrors of slavery is about more than just honoring the past. It is about how people feel in the present, and how people will treat each other in the future.

The way Middleton felt driving past that Calhoun statue, the struggle Franks faced to erect his Vesey monument, and the almost anonymous memorial to the Stono rebels all illustrate the disparity black people still face in the US.

It is almost 300 years since Jemmy and his rebels briefly broke free, and almost 200 years since Denmark Vesey was executed for trying to help others do the same. But the fight for liberty in this country has still not been won.

History is written by the winners. Apparently, the Confederacy won...

The men marched from the store to a house belonging to a white man named Godfrey. They burned the house to the ground and killed Godfrey, his wife, and his son and daughter.

When the slaves arrived at the home of a man called Lemy they killed him, his wife, and their child. They did spare a man named Wallace, who owned a tavern. He was considered a kind slave owner. But every other home they passed they torched.

And you call these killers "hero's"?

Do you think they should have chosen to remain slaves?

You can't run away without burning houses and killing children?

I support escaping - and even killing anyone who stands in your way. However, there's no particular virtue in random murder for vengeance.

I think it's his liberal white guilt talking

[deleted]

Ummm..... maybe they were angry after a lifetime of abuse?

So that makes murdering them OK?

Let's imagine you as a slave. You work long hours in your master's fields. Meanwhile, your wife is at home - a shack with a leaky roof that the supervisor hasn't given you the means to repair. There are four kids, two by you and two by the master. Two older kids have been sold away.

Your oldest, now 10, was whipped yesterday for disrespect. He hadn't actually done anything, but the master believes that there must be a whipping every few days. It was a painful experience, but the boy will live.

One of the other field hands tells you that a group will be running away, to Florida and freedom.

What would you do?

In revolts and civil wars, a lot of cultures exterminate the immediate family members to eliminate the possibility of revenge by those family members later. It's the smart move, no witnesses and no future retaliation by that family. Our last civil war was pretty civilized by those standards.

Unfortunately, we've been paying the price for not culling racist religious insurgents from society for over 150 years now. My family fought against each other in the civil war. The confederate side disinterred the union soldiers and their family members from the family cemetery during the war. After the war was over that was repaired. Seven years later there were no males left on the confederate side of the family left to disgrace our family name. Their ages made no difference.

Unfortunately it's still the culture. White Carpetbaggers from the north quickly moved into places abandoned by the Southerners from SC and GA who fled to OK and TX.

The carpetbaggers assimilated and forgot their northern roots and now drive around with bumper stickers that say

"I don't care how you do it up north" and similar themes.

They learned the racism as easily as they now believe "they, themselves" were the victims of the Civil War.

I think "angry" is a bit mild.

"Enraged" would be more appropriate, and perfectly compréhensible.

How many of these slaves had seen their own children abused?

Vengeance is wrong, of course. Killing children is wrong.

But... Slavery is worse because it includes just every crime...

Haven't you a word for the slaves who died trying to be free?

Absolutely. It happened in my family.

They burned the house to the ground and killed Godfrey, his wife, and his son and daughter....n called Lemy they killed him, his wife, and their child

Celebrating the cold blooded murder of innocent kids.... How progressive.

It's typical for some of the hard core extreme leftists.

Yes, we support slave revolts.

Don't you?

We thought y'all cared about women and children, and families being together.

They did keep the white supremacists together. They probably got put in the same hole too.

Quit trolling me and making personal insults.

[deleted]

Do you think they should have chosen to remain slaves?

I don't think burning kids to death is relevant to that choice.

They could have chosen not to remain slaves and not burned kids to death.

Do you think they should have chosen to remain slaves?

Do you think they should have chosen to not gratuitously murder children by one of the most horrifying means possible while revolting?

So, Sean... What you retain principally from the story is the deaths of the White people. The enslavement... and ultimately the murder... of the Black people is less significant for you.

That doesn't surprise me.

Saddens me, but doesn't surprise me.

So you want monuments to those who gratuitously burn children to death.

Got it.

Funny how you can't bring yourself to condemn the murder of innocent kids. Someday Bob, I hope you get past your paternalism and realize black people are full fledged, autonomous humans with agency.

It's okay to admit that burning innocent kids to death is despicable behavior.

Perhaps, it would enlighten you to hear how someone who is not blinded by a paternalistic race obsession processes evil acts in a worthy cause.

The native Irish of the 18th century were, by any standard, grievously oppressed by the English colonists. Not to the extent of slavery, surely, but enough so that violence was not an extreme response. Thus, the United Irish Revolt of 1798, that was a valiant, miserable failure of an attempt to overthrow the English and set up a republic in which Irish Catholics would be recognized as full fledged humans.

The revolt centered around Wexford, and as I have family that comes from adjoining Waterford, may well have included my ancestors. In the run up to one of the determining battles, loyalists were put in a barn and burned to prevent any information from being leaked to the English.

Here's the difference between you and I, Bob. While I believe the cause of the Irish was just, their actions at Scullaboge barn in slaughtering women and children with the thinnest of military of justifications was inexcusable and horrific. It would be a travesty to put up a marker honoring the Irish rebels at Scullaboge, simply because their cause was just, as if a just cause somehow turns objectively barbaric acts against innocents into heroic deeds.

But it is appropriate that t here is a Scullabogue Memorial stone in the graveyard of Old Ross Church of Ireland church. The theme is one of reconciliation.

There is, however, no state memorial to the people who were massacred during this incident.

Possibly because the fires were set by men who escaped from the Battle of New Ross

and correctly conveyed the fact that the British had set fire to a home used as a surgery by the rebels,

killing all of the wounded rebels inside.

Additionally the prisoners at Scullaboque included dozens of Catholics and the guards were predominantly Protestants.

Facts matter.

Having memorials for historical events neither excuses the participants or makes heroes of them.

So does reading comprehension. I'm glad you took two minutes to read a Wikipedia page on this.

ut it is appropriate that there is a Scullabogue Memorial stone in the graveyar

Of course it is. Would it be appropriate to honor the rebels who burned the women as children in a barn as heros? That's the issue, not whether a simple marker is appropriate. You should probably re read this entire article if you think if I'm objecting to the marker acknowledging the occurrence. If you want to persist in arguing against a straw man go ahead if it makes you feel better.

ibly because the fires were set by men who escaped from the Battle of New Ross

yes. They'd fled the battle and set fire to the barn. Does that make them heroes? Because that's point in contention.

I guess you think the burning of woman and children in a locked barn is heroic if it's in retaliation for the killing of a couple rebel soldiers. I guess we'll have to disagree, because I don't think burning kids in a barn is a heroic act, no matter the provocation or how righteous the rebellion.

onally the prisoners at Scullaboque included dozens of Catholics and the guards were predominantly Protestants.

Does that make it heroic? This certainly isn't a point in contention, I wonder why you brought it up. does the fact hat both catholic and protestants loyalists were burned make it a heroic act?

Again, if you'd read what I wrote, you'd see I was objecting to calling the cold blooded murderers of children heroes, I'm fine with a historical marker and this one seems perfectly appropriate. I, unlike the author, don't want to lionize a drunken mob that slaughtered children. If' that's the hill you want to die on, go ahead.

Bob, would you agree that French jews could burn the children of Vichy French to death? If so, what about their grandchildren? At what point is is no longer a heroic act to murder the children of your oppressors?

Sean... You say a lot of stupid shit... but this is among the stupidest shit you've ever posted...

Well said.

Well, it's a way, and better than nothing. A lot of really dramatic historical events are commemorated across the country with plaques at the side of the highway. I have pulled over for many of them and learned a lot of history that way. Sometimes, it's kind of amazing. You're in the middle of nowhere and you find out dozens of people died on this spot for some cause and you wonder how many people drive by totally unaware of it. Was it all worth it?

However, the larger point is well-taken. We should have more prominent statues and memorials for people who fought slavery.

I don't live in the South. I wasn't raised there. I, personally, would not want huge statues for slavery advocates in my town, but I can't tell these people how to live their lives.

It isn't "Right" !

Take down the sign.

Right ?

Did a little fact checking , this incident may have had the distinction of being one of the first but it wasn't the largest in the colonial era .

It is dwarfed in numbers by the New York City conspiracy of 1741.

I will say it most likely set the stage for how such incidents were reacted to .

According to WIkI this is what one plague says, although I never stopped to read it, I passed it daily for a long time, probably bought gas at that gas station.

Although there is no evidence of how they murdered more than twenty people it is unlikely that any were burned to death.

The Cato mob was on a mission to escape to Spanish Florida as quickly as possible.

Having been stumbled upon and discovered by a plantation owner's hunting party, the SC militia blocked the runaways at the Edisto River and overwhelmed them

but at the cost of 20 plus white casualties.

Escapees were again cornered the following week and most were executed.

As the author indicates, one can drive past Hutchinson's Wharehouse site and not realize that it is National Historic Place.

Why? The way this source is written it's a fair inference.

And is it better if they dragged little kids out of their houses and executed them? Is that type of cold blooded execution of children worthy of being honored?

If the slaves murdered that child then the slaveowners murdered many many many more

That's a reprehensible justification for the murder of children. You think it's okay to kill kids in cold blood because other people of the same race acted badly? It's barbaric to kill kids for the wrongdoings of others.

Dear Sean,

First of all if Cato had burned people alive that would be part and parcel of the story especially in South Carolina, British colony or American State.

Maybe you would have had to have lived there to "appreciate" that.

Secondly, historical markers on a highway are exactly that. Reminders of what happened on that spot decades ago or a hundred years ago or a thousand years ago.

A marker doesn't demonize or make heroes out of the subjects .

A historical marker is there to educate, lest we forget and repeat our mistakes.

and speaking of mistakes, whose quote is this ???

because I certainly didn't make it.

So take your sanctimonious umbrage and false claims of my "reprehensible justification" and kindly stick it,

or direct it at the appropriate party.

My mistake, I thought the same person authored your and the subsequent post.

Since your post consists of arguing against points I didn't make, [delete]

arker doesn't demonize or make heroes out of the subjects .

First, of course it can. Second, my point is not about this marker. Look at the title. It calls people who murdered bloods in cold blood heroes. Mark the occurrence with a marker, no one's contesting that despite what you wrote. The point, which you mange to avoid, is that the author wants the child murderers to be honored as heroes.

By all means, make the case why the killers of innocent kids should be called heroes.

I have the feeling Mr. Godfrey was not a "kind" slave owner. It is a tragedy that his child had to pay for the father's sins with his life. There is a good chance the wife was not at all innocent.

I don't recall ever seeing on this forum or any place like this, where the white commenters get all upset at the particulars and details of the slave trade, when Africans were packed into the underbelly of vessels so tight that they just defecated where they lay. Many slaves went mad and leapt over the side of the ship at first chance and drowned themselves.

Let's stop with the facade of claiming that the slaveowners were misunderstood. If the slaves murdered that child then the slaveowners murdered many many many more. Of course the slaves were not white , so their rage is not given any justification by "conservatives" today.

That's the essence of it.

No compassion for slaves trying to break free... what happens to Black people is unimportant.

White people were killed... That is terrible!

No racism, here!!

They weren't "jerks". They were slave-owners. They were people who abused other people to force them to obey.

How can you ignore the context?

Imagine that you have been abused all your life, beginning when you were a little girl. Perhaps your owner found you attractive... or simply made a habit of impregnating all his women. No matter, you go to his bed or get whipped for disobedience. You have borne three children for him. When each reached six years old, he sold them.

Would you be angry?

Murderously angry?

The folks who read this and immediately came to the conclusion that the slaves who killed women and children were ruthless barbarians, are probably the same kind of people who wring their hands and gnash their teeth at not getting into the college of their choice, or not being served fast enough at the restaurant, or losing WiFi connectivity on a flight. People who fixate on their WPP (white people problems), have no capacity for understanding the very real oppression that minorities face every day.

Like what for example? They've never had so good, thanks to the GOP making life better for everyone, not just select groups.

There are some who insist that Blacks were much better off as slaves.

Yeah, we know all about how the deplorables treat minorities.

https://youtu.be/2LX4Q643aEU

Bob , you can call this off topic if you wish , and if you do I apologize ahead.

personally, I love history , not the sanitized , the winner gets to write the history books type , but the dirty real history.

What I try to remember when I am looking things up , is that as a child of the late 20th century, and an adult ( cut me a sprout there please) of the early 21st century, is that I am viewing things that are influenced by beliefs , practices , conditions and laws that exist today , not in the framework of the times that the events I am studying happened. and I point out that all those things I mentioned have changed , some not as much as some would like .

You're absolutely correct. Looking at events of a couple centuries ago with today's social standards would be a serious anachronistic error.

In this case, slavery was not yet widely condemned. That would come in the next half-century.