Theresa May’s Impossible Choice

With Brexit looming , the Prime Minister is battling Trump, Europe, and her own party.

Illustration by Andrea Ventura

The British Prime Minister, Theresa May, often strikes people as cautious, but her political career has been defined by acts of boldness, often on behalf of unfashionable causes, or in the face of seemingly impossible circumstances. The misconception arises in part because she is an awkward person. May, who is sixty-one, is tall and stooped, serious and shy. Since she was elected to Parliament, in the late nineteen-nineties, she has dressed in sharp, eye-catching clothes, as if to offset the fact that she is not personally vivacious, but the effect is often to accentuate what is not there. May doesn’t say much, by anyone’s standard, let alone that of a politician. On a recent sunny afternoon, in the garden of the Prime Minister’s residence, at 10 Downing Street, I watched her being guided by an aide through the beginning of a party to mark London’s Pride celebrations. As May was introduced to a line of leaders from Britain’s gay and transgender communities, she smiled each time and then started to nod. She nodded faster, dozens of times, to encourage them to say more. She extended her neck, like a bird leaning over a pond, nodded a final time, and moved on. She scarcely said a word.

May is quiet in government meetings, too. “She sits, you talk. She sits. She looks at you, and then you leave,” a former Cabinet colleague told me recently. May’s preferred method of communicating with the public is in the form of long speeches, which she delivers with a certain steel. She can land a joke, if she has time to prepare. But when she is forced to speak off the cuff, in Parliament or to the press, her body stiffens and she takes deep breaths. She has a wide, expressive mouth that cracks into grimaces and betrays an inner tumult, while the sentences that emerge are frequently circular and devoid of clear meaning.

As a result, it is hard to sense what May is thinking or to predict what she will do next. “No one knows where they are at any point in time when they are working for Theresa May,” one of her former staffers said. May rejects the inevitable comparisons to Margaret Thatcher, Britain’s first female Prime Minister, because Thatcher had an agenda that was overtly ideological. May, unlike Thatcher, would not enjoy being photographed driving a tank. Her definition of politics is “doing something, not being someone.” People say that she would have made a fine lawyer or judge. But she happens to be the leader of the United Kingdom—a divided nation of sixty-five million people, Europe’s second-largest economy, and America’s closest ally—as it chooses how it wants to proceed in the world. This summer, that choice, which is frankly overwhelming, came to rest with May. Britain waited and watched. May made her call, and then her government more or less exploded. And that was before Donald Trump showed up.

May, who is a member of the Conservative Party, became Prime Minister two years ago, on July 13, 2016, twenty days after the British people voted to leave the European Union. Her predecessor, David Cameron, who had called the referendum, resigned immediately, bequeathing the crisis to May, who had served in his Cabinet. Brexit is not the most riveting, or easily graspable, recent meltdown in a Western democracy. In other countries, majorities have elected leftists, like Andrés Manuel López Obrador, in Mexico; or dynamic centrists, like Emmanuel Macron, in France; or strongmen, like Trump, to address their fears about economic and cultural change. In Britain, voters put their faith not in a previously unthinkable person but in a previously unthinkable policy.

In the Brexit referendum, 17.4 million people, or fifty-two per cent of voters, chose to take the country out of the E.U., a vast supranational project that had become a metaphor for a remote and unfair system for organizing people’s lives. But the decision presented a great democratic problem. Staying in the E.U. could mean only one thing, but there were any number of ways to leave. No country has ever left the E.U., and the states on its borders have a spectrum of relationships with the bloc. They range from near-members, such as Norway and Switzerland, which between them pay the E.U. hundreds of millions of euros every year and accept many of its rules and migration policies, in order to take part in its single market; to Turkey, which is part of the E.U.’s customs union and therefore coördinates many of its international trading arrangements; to Russia, which is a quasi enemy.

Britain is a leading military power and Europe’s financial center. It joined the European Economic Community, as it was then known, in 1973, and spent the following four decades as an influential, if sometimes ornery, player in the development of the bloc. The country’s history, international profile, and economy suggest that it should seek to stay as close as possible to the E.U. after its departure. On the other hand, its people have asked to be free. The siren call of the Brexit campaign, which was led by anti-E.U. populists, such as Nigel Farage, and by a rump of charismatic Labour and Tory M.P.s, like Boris Johnson, was for the U.K. to “take back control,” and to regain its distinctive identity in the world.

Since the referendum, the central task in British politics has been to try to square two conflicting demands: to respect the democratic impulse of Brexit while limiting the economic consequences. It is a version of the challenge posed by populist anger everywhere. How far should governments go in tearing up systems that people say they dislike—the alienating structures of global capitalism and multilateral government—when the alternatives risk making populations poorer, and therefore presumably more furious than before?

May’s best hope has been to contain the damage on all sides. Between 2016 and 2018, the U.K. went from being the fastest-growing major economy in the world to the slowest, as businesses halted investment plans, migration dwindled, and foreboding filled the air. The government’s own estimates show that every form of Brexit will make people worse off, ranging from a relatively modest impact, if the country ends up somehow entwined in the E.U.—and thereby less free—to a cost of around eight per cent of G.D.P., if it leaves with no formal deal at all.

May opposed Brexit. Unlike many Conservatives, she never developed a theological conviction, either way, about the European Union. It was ungainly, but it was there. “She thinks it is a bit of a ridiculous debate,” a former aide said. It is easy to sympathize with her, because of the extreme views of some of her colleagues and the formidable nature of the task that she faces. “There is a question about whether anyone can do this,” the former Cabinet colleague said. But May’s reluctance to share what she is thinking has made her an erratic leader. In her first year in office, with little consultation, May adopted a hard-line approach to Brexit, which appeased the anti-E.U. wing of her party but startled governments across the Continent. In the spring of 2017, May called and ran a disastrous general election, in which she sought to reorient the Conservative Party toward struggling, middle-class voters, many of whom had voted for Brexit, and to strengthen her mandate in Parliament. But, instead of adding to the Conservatives’ slender majority in the House of Commons, which Cameron had won two years earlier, she lost it. May barely survived; for the past year, she has been forced to rely on the votes of the small, far-right Democratic Unionist Party, from Northern Ireland, in order to pass key legislation in Westminster.

After the election, May’s premiership became even more strained and subdued. Several of her closest advisers resigned, leaving her further isolated. Once the formal Brexit negotiations with the E.U. began, last June, ministers and officials bemoaned the absence of a leader’s voice. “There is no vision. There are no objectives,” a senior official told me. “There is ‘How do we muddle through this?’ Sometimes from hour to hour.”

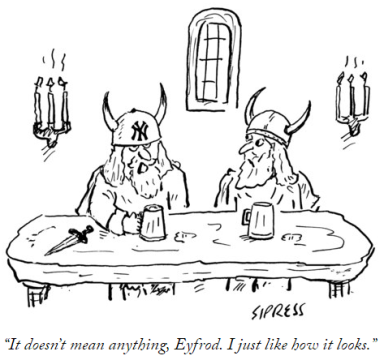

“It doesn’t mean anything, Eyfrod. I just like how it looks.”

This summer, the pressure on May to define Brexit became immense. For several weeks, I watched her move among a rancorous House of Commons, a divided Cabinet, and a recalcitrant E.U. (She declined to speak to me.) At the same time, Trump marauded, destabilizing the international order into which Britain is about to reëmerge, alone. No one I interviewed envied May, or wished to take her place. A former minister compared her position to being inside Little Ease, a windowless torture chamber in the Tower of London, where it was impossible for prisoners to stand, sit, or lie down. “It is getting tighter and tighter,” the former minister said. “Something has got to give.” In the course of ten days in July, it did.

Three weeks earlier, on a hot June morning, I took a train from London to Dover. The town lies seventy-five miles to the southeast and is unlovely, cramped between the cliffs and the sea. Half a million years ago, you could have walked to France along a twenty-mile chalk ridge, and, for all of Britain’s recorded history, Dover has functioned as the country’s principal meeting point with the rest of Europe. Work on the town’s defenses began after the Norman invasion of 1066. Waterloo Crescent, a little street near the shore, is named for Napoleon’s final defeat. A plaque in the docks commemorates the more than two hundred thousand Allied soldiers who were evacuated from Dunkirk to Dover.

For the past quarter of a century, however, the town’s niche has been seamless trade with the European Union. In 1993, under the rules of the customs union and the single market, virtually all checks on trade between Britain and the rest of the Continent were eliminated. The French coast is ninety minutes away by ferry, and trucks carrying flowers, lemons, clothes, wine, aluminum, and automotive parts trundle in and out of the port at all hours. Dover is a small place; its population could fit into Staten Island twelve times over. In 2017, seventeen per cent of the U.K.’s trade in goods passed through the town.

The trucks leave the docks on the A20, a busy road that cuts off the waterfront from the rest of Dover. I walked along the sidewalk as the bright liveries of European shipping companies—Waberer’s, of Hungary; Amenda, of Germany; Finejas, of Lithuania; Discordia, of Bulgaria—buffeted past. A hitchhiker held out his thumb; he was trying to get to Glasgow. On a good day, ten thousand trucks pass through Dover. Around five hundred of them, carrying goods to and from non-E.U. countries, turn off the main road and cross a viaduct back toward the water, to the port’s last remaining customs clearance. Since 2012, all freight inspections in Dover have been handled by a company called Motis. The Motis facility is a windswept parking lot with a cafeteria, a laundromat, and showers for drivers. It stands on the old Dover Marine railway yards, where more than a million wounded soldiers were brought home from the First World War. At the gate, where heavy trucks make a tight turn to enter, cracks in the asphalt reveal nineteenth-century cobblestones below.

In the office, a few drivers lined up with their paperwork. A radio played. Tim Dixon, a Dovorian in his early fifties, was in charge. Dixon wore a suit under his high-visibility jacket; his office shoes were speckled with dust. Since he started working in customs, thirty years ago, Dixon has watched Dover’s port, piers, and road system evolve to serve the “just in time” supply chains that send semiconductors, half-built car engines, and freshly caught squid back and forth across Europe mere hours before they are needed. Honda’s main U.K. plant, in Swindon, keeps only a day’s worth of E.U.-imported parts on hand.

In January, 2017, May announced that Britain would withdraw from the rules and systems on which those supply chains have been built; namely, the E.U.’s single market, which harmonizes product standards across the Continent, and its customs union, which allows goods to move freely inside the bloc. “I have an open mind on how we do it,” May said. “It is not the means that matter, but the ends.”

Dixon has been in meetings preparing for Brexit ever since. “It was Hellfire Corner in the war,” he said. “It feels like that again now.” He rattled off the various delegations that have come and fretted in his office: the Border Planning Group, the Southern Corridor Working Group, Fujitsu, the Kent Strategic Freight Group, the Home Office, the Department for Exiting the European Union, known as Dexeu. “They are all separate departments, all saying slightly different things,” Dixon said. “My concern is that not everyone is singing from the same hymn sheet.” All manner of ideas—in the form of license-plate recognition, digital registration, and inland barriers—have been proposed for Britain’s theoretical new borders with the E.U. But any checks are going to be worse than no checks. According to the Port of Dover, adding two minutes to the journey of every truck coming through the town will lead to a seventeen-mile traffic jam.

The Motis site has three inspection bays. On the morning I visited, a Slovak truck was parked with its tarpaulin sides open, carrying diesel generators bound for Iraq. It was almost two years to the day since the Brexit vote, and May’s government had still not settled on a plan for its new customs relationship with the E.U. The likeliest option, it is estimated, will cost businesses twenty billion pounds a year and take five years to develop. (After Britain leaves the E.U., it is expected to enter a twenty-one-month transition period before any deal takes effect.) I asked Dixon, who has a team of five, whether he was planning to hire more staff to prepare for the exit, an event known in customs circles as Day One. Dixon shook his head. “We haven’t got a contingency plan, because we don’t know how things are going to operate,” he said. Dixon didn’t sound panicked; he sounded as though he might quit. A friend of his, another freight agent, had suffered a heart attack the other day. “There’s no way I would go back into customs clearance,” he said. “No way. Not if someone offered me a villa in Marbella.”

Dixon voted for Brexit. When he was growing up, in the seventies, Dover had a local coal mine, a paper mill, and a metalworks, though the harbor, then as now, was the main source of work. “When I left school, it was, ‘Get a job in the port. You are made for life,’ ” Dixon said. At the time, the bureaucracy of international trade was almost as labor intensive as the physical handling of the goods. Freight agents were crammed into attics and basements all over town. The port’s customs and immigration depots were large enough to field their own soccer teams, which played on Wednesday afternoons.

In the eighties, Dover declined, like other industrial towns across the U.K., but the coming of the single market, on January 1, 1993—and the efficiencies that it wrought—was a particular blow. A thousand jobs disappeared overnight. Then the Channel Tunnel rail link opened, just down the coast. Ferry services were reduced, and unemployment in Dover hit twenty-five per cent. The new proximity of Europe also brought increased migration. In 1997, a wave of Roma asylum seekers arrived in Dover and took over Folkestone Road, a street of old Victorian guesthouses, which became known as Asylum Avenue. The Roma left, but the event is still talked about in the town, whose population is overwhelmingly white and British-born.

“Even the kids today are, ‘Ah, the immigrants,’ ” Dixon said. “Rightly or wrongly, it’s in their heads.” In recent years, many of Britain’s coastal communities have slipped behind the rest of the country in measures of income, education, and health, giving rise to an over-all feeling of depression and ill health which is recognized informally by doctors as S.L.S., or Shit Life Syndrome. A regeneration plan for Dover, published by the town’s businesses and politicians in January, 2016, noted “a high degree of cynicism in the local community and a feeling that the town’s problems are ignored.” Five months later, when the Brexit campaign offered Dovorians a chance to take back control of their lives, sixty-two per cent took it.

Two years later, people have their own explanations for why the shape of Brexit has been slow to materialize. At the town’s waterfront hotel, I met Charlie Elphicke, Dover’s Conservative M.P. Elphicke voted Remain, but he has since emerged as a vocal Brexiteer. Last July, he published his own infrastructure plan for Dover, “Ready on Day One,” whose recommendations included building a new crossing over the River Thames. Nothing followed. “This is the biggest national project since the Second World War,” Elphicke told me. “And yet parts of government are treating it like it is some kind of Thursday-afternoon reorganization.” Like many Tory Brexiteers, he complained about May’s failure to engender a feeling of “national mission.” When I asked Elphicke if he thought the Prime Minister believed that Brexit was a good thing for the country, he replied, “Every time she is asked this question, she doesn’t answer it.”

The greater obstacle is the granular difficulty of the task. Brexiteers yearn—and May has always promised—to take Britain out of the customs union, because that is the only way to strike independent free-trade deals with nations like the United States and China. By definition, exiting the customs union requires Britain to have a new set of border arrangements with the E.U. That is daunting enough in a place like Dover, but it’s another story entirely in Northern Ireland, where any plan for a physical frontier between it and the Republic of Ireland—after the bloody history of the Troubles—is regarded as politically infeasible. For the past year, the Irish-border question has proved one of the Gordian knots of the Brexit negotiations. The E.U. has proposed that Northern Ireland stay inside the customs union and the single market while the rest of the U.K. leaves. But this would create an internal British border in the Irish Sea, something that, earlier this year, May told the House of Commons, and her parliamentary allies, the strongly unionist D.U.P., “no U.K. Prime Minister could ever agree to.”

And that’s Brexit, in a way. “Every single element in this is connected,” the senior official told me. The mightiest riddles, such as the customs union, have dominated the political conversation, but the truth is that it’s nitty-gritty all the way down. During its forty-five years in the E.U., Britain has imported around nineteen thousand European laws and regulations. The fabric of the acquis, as the legal framework is known, is the fabric of political life. E.U. articles and directives govern everything from equal pay for men and women to the international trade of the hairy-vetch seed. Two days before I went to Dover, a fourteen-page update from the Brexit negotiations included progress on the status of staff employed on British military bases in Cyprus, the ownership of fissile nuclear materials, and the future administration of sales taxes. One of the reasons that people voted to leave the E.U. is its totalizing nature, and the sense that it had penetrated too far into British life. But the years of membership, the weaving of the acquis, have constructed a reality that is hard to change—and even harder to imagine a life outside.

Before I left Dover, Dixon drove me up to its western heights, for a view over the town. France was a hump across the sea. Midges buzzed around Dixon’s fluorescent vest. Cranes worked below. In January, 2017, after years of planning, construction began on a project, costing two hundred million pounds, to create a new cargo terminal and marina at Dover’s western docks. Before Brexit, the port’s trade was forecast to increase by forty per cent by 2030. Dixon looked down on the scene and observed that the project is partly funded by the E.U. “Which is a real kick in the bollocks, isn’t it?” he said. Confronted by the practical difficulties of Brexit, Dixon told me that he would probably choose to stay in the E.U. if he had his vote back. Unlike Elphicke, the M.P., he didn’t blame May for refusing to believe. We sat in his car. The Prime Minister may not communicate well, but many people see her as a reasonable person caught in a situation of great unreason. Her approval rating hovers at around forty per cent. “I’ve actually warmed to her,” Dixon told me. “I didn’t think I’d hear myself say that.”

Before May joined Cameron’s government, she was best known for wearing leopard-print shoes. She was first elected to the House of Commons on May 1, 1997, the date of Tony Blair’s landslide victory for New Labour, which removed the Conservatives from power after eighteen years. It was a desperate time for the Party, which was tired, male, and regressive. In May’s maiden speech to the House of Commons, she joked about being mistaken for an incoming Labour M.P. simply because she was a woman. (The Tories had thirteen female M.P.s at the time, the same number as in 1931.) May was forty, and represented the new parliamentary seat of Maidenhead, in the commuter belt west of London. With her husband, Philip, who now works for an investment fund, May had been active in student politics at Oxford (they were introduced by Benazir Bhutto, who later became the Prime Minister of Pakistan) before she took a job at the Bank of England.

During her party’s long years of opposition in Parliament, May took on progressive causes, such as instituting shared parental leave and encouraging more female candidates. “She was a modernizing female Tory,” a former Cabinet aide told me. But May was also connected to the Party’s traditional side. She grew up as the only daughter of an Anglican priest, Hubert Brasier, in Church Enstone, a small village in the Cotswolds, and in her teens started stuffing envelopes for local candidates. Last year, she told an interviewer that the naughtiest thing she did as a child was to “run through fields of wheat.”

https://media.newyorker.com/cartoons/5b527193974e112fa0c971f9/master/w_727,c_limit/180730_a22044.jpg

When May was twenty-five, her father was killed in a car accident. Her mother, Zaidee, died a few months later, of multiple sclerosis. Unusually for a senior British politician, May regularly takes Communion. In 2014, appearing on the BBC radio show “Desert Island Discs,” she chose an Anglo-Catholic hymn, “Therefore We Before Him Bending This Great Sacrament Revere,” which she used to sing with her parents in an empty church. “I do think there is an inner life,” the former Cabinet colleague said. “But I think it is one that would have been more recognizable to people in a pre-liberal age.”

When the Conservatives returned to power in 2010, in a coalition with the Liberal Democrats, Cameron put May in charge of the Home Office. The department was traditionally responsible for prisons, border control, the police, and the security services. Under Labour, it had chewed through six Home Secretaries in thirteen years and had come to be seen as unmanageable. Although the department was slimmed down in 2010, May held the job longer than anyone had since the Second World War. “If she had to be at a meeting at half past seven in the morning, she was there,” the former staffer said. “Fully made-up. Ready to go.”

May confronted long-standing issues that were risky for her and for her party. In 1989, ninety-six fans of the Liverpool soccer team were crushed to death in the stands of Hillsborough stadium, in Sheffield. For years, the catastrophe—and the defensive response by the police and by Thatcher’s government—was a symbol of the Conservative Party’s disdain for working-class communities in the North. In 2012, May announced a criminal investigation into the causes and policing of the disaster.

May set up units in the Home Office dedicated to solving previously intractable problems. In 2013, the department succeeded in deporting Abu Qatada, a notorious Al Qaeda spokesman, to Jordan, after a ten-year court battle. “We went out to Jordan and we just fixed it,” another official said. “No one had come up with that approach before.” In 2014, May addressed the Police Federation, a union of England and Wales’s forty-three police forces, and accused officers of having contempt for ethnic minorities and victims of domestic violence. “I am here to tell you that it’s time to face up to reality,” May said. The speech was met with silence.

She was detached and impressive at the same time. “I think she sees herself as an outsider,” Nicky Morgan, who served as an Education Secretary in Cameron’s Cabinet, told me. “She sees and hears people’s frustrations with the system that says no, with the establishment which doesn’t shift.” Lynne Featherstone, a Liberal Democrat, was a minister in the Home Office under May, as part of the coalition with the Conservatives. The two women worked together to introduce Britain’s legislation enabling same-sex marriage, which passed in 2014. “She is never completely not awkward,” Featherstone said. But Featherstone was struck by May’s resolve, even on divisive questions—the marriage law was unpopular among many traditional Tory voters—once she had committed to something. “When she gets an idea, and is sure of it, she goes for it,” Featherstone told me. “Absolutely goes for it. And she doesn’t really care about anything else.”

Until the very moment of decision, though, May’s opinions have often been hard to fathom. She served for a year as the Conservative Party chairman during the Blair years, the depths of the wilderness. In October, 2002, in a blunt speech at the Tories’ annual conference, she urged the Party to reform, in order to broaden its appeal. “You know what some people call us—the nasty party,” May said. The “nasty party” speech is now credited with helping to bring about the rebranding of the Conservatives under Cameron, but May did not write it, or its telling phrase. “Most big speeches start with the politician, the leader, the speechmaker, giving a sense of what they think,” a former Party official, who worked for May at the time, told me. “We didn’t get any of that.” Much of the speech was written by a young adviser named Chris Wilkins. When the “nasty party” line was inserted in the text, Wilkins alerted May to the potential risks. “We went back and forth the whole week,” he told me. “Eventually, she just fixed me with that stare and said, ‘Chris, I am going to say it.’ ” Later, Wilkins worked for May as her speechwriter in Downing Street. He told me that someone in her presence casually referred to Cameron and George Osborne, the former Chancellor of the Exchequer, as modernizers of the Party. “I was the original modernizer,” May replied.

May’s simultaneous fixity and willingness to rely on her advisers has led people to wonder whether she is brittle, or wary of her own instincts. A former senior civil servant who worked for her told me that she has cut off officials when they start to argue in front of her. “Theresa very rarely has more than one opinion in the room,” the former Party official said. Throughout her career, May has allowed trusted deputies to filter information and options on her behalf. “If you are let into that, you are given a huge amount of power and agency,” one of them told me. “The downside of that is that she often accepts people’s judgment without necessary criticism.”

During her time at the Home Office, May stuck relentlessly to a target of reducing net migration to the U.K. to the “tens of thousands” per year—a Conservative Party promise from 2010. The issue was largely beyond her control—more than forty per cent of the U.K.’s immigration comes from E.U. citizens’ right to “freedom of movement.” In 2015, net migration to Britain reached three hundred and thirty-two thousand. Yet May never sought to modify the target. In 2012, she declared her intention to create a “hostile environment” for illegal immigrants, and began a crackdown that required employers, landlords, and National Health Service staff to start asking for evidence of people’s immigration status. The policy ensnared thousands of people who had come to Britain decades before—many from the so-called Windrush Generation, who migrated from the U.K.’s former colonies in the Caribbean—and had never been formally naturalized, along with their children. Reporting by the Guardian last year revealed that dozens of British citizens had been wrongfully deported.

At the Home Office, May came to depend on two advisers, Nick Timothy and Fiona Hill. “They went to every meeting,” the former Party official said. “They read every paper. They stopped it before it went to her, and they were the last people out of the office at night.” Timothy, a former deputy director of the Conservative Party’s research department, grew up in Tile Cross, a working-class neighborhood in Birmingham; Hill started out as a sports reporter in Glasgow. Like May, the two believed in a more interventionist and traditional conservatism than the privileged, socially liberal outlook of Cameron and Osborne. In Westminster, Timothy and Hill jealously protected May’s authority. Officials in other departments became accustomed to a certain style of Home Office decision-making, which was slow, competent, and abrasive. (In 2014, after a confidential memo was leaked to discredit Michael Gove, who was then the Education Secretary, Hill was forced to resign.) “A lot of senior politics is compromising, and they didn’t compromise,” a former Cabinet Office official told me. “Some of the best people I have ever seen just don’t give a shit.”

After three years in the Home Office, May gave a speech to Reform, a center-right think tank, in which she spoke about the country’s deficit and its health service, roaming far beyond her official brief. The speech was widely considered an attempt to position herself as a rival to Cameron. Late at night, May, Timothy, and Hill often talked about broader issues facing the nation. Politicians who admired May encouraged her to aim for Downing Street. “I have always thought she had the potential to be Prime Minister,” Featherstone told me. “I had that conversation with her.” But May didn’t work the House of Commons tearooms, or have an obvious base within the Party. “It didn’t look like a classic political bid,” the former Party official told me. “Everybody thought it was all Nick Timothy.”

Six months before the E.U. referendum, Cameron declared that Cabinet ministers could campaign for either side, freeing Gove and Johnson to make the case for Brexit. May did not join them. “She came to Remain political cabinets,” the former Party official said. “She contributed to discussions about the Remain campaign internally.” Publicly, however, May said little. During her time in the Home Office, E.U. rules frequently frustrated May and her team. She led a successful renegotiation of Britain’s commitments to the bloc’s crime and security regulations but did not identify with the Conservative Party’s vociferous Euroskeptic faction. “The chances that she would be a Brexiteer were zero, in my view,” the former Cabinet aide said.

As the referendum debate intensified, May stayed on the sidelines. “She only did two speeches during the whole campaign,” Will Straw, the executive director of the official Britain Stronger in Europe campaign, told me. “This was the Home Secretary, who could have been a really significant voice.” In a memoir published after the campaign, Craig Oliver, Cameron’s communications director, counted thirteen occasions when May was asked, and failed, to contribute. “Amid the murder and betrayal of the campaign, one figure stayed very still at the centre of it all—Theresa May,” Oliver wrote. “Now she is the last one standing.”

The morning after the referendum, when David Cameron resigned, he offered to stay in office until the Conservative Party had chosen a successor, a process that was expected to last until the fall. Within a week, however, Johnson, who had been the initial frontrunner, withdrew from the race, and Gove, who had been expected to back Johnson, sought to become Prime Minister himself. The bickering damaged the Brexiteers and enhanced May, who was left as the senior Party figure in the contest. Her main rival turned out to be Andrea Leadsom, an inexperienced, pro-Brexit energy minister, who told the Times of London that “being a mum” would make her the better leader. (May and her husband were unable to have children.) On July 11th, Leadsom dropped out, and May took office unopposed. “We got her eight weeks before anybody expected,” a former civil servant told me.

As Prime Minister, May immediately established two new government departments: Dexeu, to manage the Brexit process; and the Department of International Trade, to explore economic opportunities outside the E.U. Dexeu was given offices at 9 Downing Street, the former premises of the court of the Privy Council. In their first weeks, civil servants worked in the docks and on the benches of the old courtroom as they grappled with the scale of Brexit. “People were saying, ‘How does the U.K. fishing industry work? How does the U.K. automotive industry work?’ ” the senior official told me. “You were getting papers saying, ‘There are lots of fish in English waters.’ Literally, they were at the most basic level.”

From the top of government, however, there was silence. During her short campaign, May had coined the phrase “Brexit means Brexit,” to indicate that she would honor the result of the referendum. But she said little more. Soon after May appointed her first Cabinet, in which she named Johnson Foreign Secretary, M.P.s and senior officials began to leave for their summer vacations. “I thought, This is very odd,” the former minister told me. “Why are we all going away, when there is a sort of national crisis going on? You know, where are the meetings?” Aides in Downing Street noticed a similar absence of activity. “I expected to find the government completely obsessed with dealing with Brexit. Actually, that wasn’t what was happening at any level,” one of them said.

For the first months of May’s premiership, there was a Brexit meeting in her office on Wednesday afternoons, attended by around a dozen senior officials. Timothy and Hill had joined May as her chiefs of staff. Because of the fractious state of the Cabinet, which was split between Brexiteers and Remainers, and the feverish media attention, Timothy and Hill sought to keep access tightly controlled. Senior civil servants, who were used to boisterous meetings in Cameron’s Downing Street, were struck by the formality and quietness of working with May. “She just says, ‘Tell me more,’ ” the former civil servant told me. “So you spiel.” Ministers came to suspect that the true decision-making circle was even smaller, with Timothy—who was strongly pro-Brexit—shaping the policy. “The Brexit group never grew,” the former Cabinet colleague told me. “Because it was Nick and her.” (Timothy denies this.)

May presented her thinking in the form of speeches. In her first major address on Brexit, at the Conservative Party conference in early October, 2016, May made it clear that Britain would no longer accept unlimited immigration. Given that free movement is a condition of being part of the single market—and accepted by non-E.U. members such as Switzerland and Norway—the speech indicated that the U.K. would seek a decisive break.

May declared, “The authority of E.U. law in Britain will end.” The line sounded technical, but it caused great shock outside the U.K. Withdrawing from the European Court of Justice meant that May intended to take Britain out of more or less every regulatory mechanism devised by the bloc, from drug safety to aviation rules. Senior officials working on Brexit were also astonished: there had not yet been a detailed discussion of the E.C.J. with May and her team. “They didn’t know what it meant,” the civil servant told me. The pound fell sharply, and European governments began calling, trying to decipher May’s intentions. “You think, Oh fuck. This is going to be fun in Brussels.”

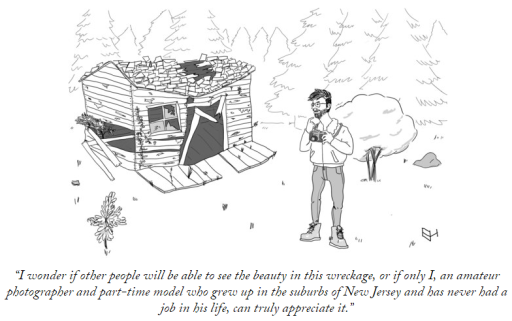

“So, is this a date with destiny?”

In May’s first six months in Downing Street, she intimated a form of Brexit that would give the U.K. looser bonds with the E.U. than Iceland and Turkey have. Her speeches carried enormous implications for the way that British life was organized. Ministers who had voted to keep the country in the E.U. were dismayed by their lack of access to the Prime Minister and feared that she was too dependent on Timothy, who was considered brilliant but inexperienced. The former Cabinet colleague told me that Timothy’s reading of Brexit “is accurate but unrealistic, and would crash the economy.” The civil servant told me of May, “You can do that in the Home Office and operate like that, with a small coterie of people around you. In No. 10, you can’t.”

By late 2016, May’s approach to Brexit was causing rifts at the top of government. Philip Hammond, who had succeeded George Osborne as Chancellor, was alarmed about the potential impact of May’s decisions on the economy. Timothy took a dislike to him, and Hammond was frozen out. “Nick decided that he is a cunt,” the former Cabinet colleague said. “And once he is a cunt you never come back.” Other Conservatives arguing for a milder Brexit were also punished. After Morgan, the former Education Secretary, questioned the wisdom of May’s wearing a pair of pants costing nearly a thousand pounds, in a photo shoot for the Sunday Times, Hill banned her from Downing Street. “Don’t bring that woman to No 10 again,” Hill texted a fellow-M.P. “The point was, you were either in the camp or you were out,” Morgan told me.

On January 3, 2017, Rogers, the U.K.’s senior diplomat at the E.U., resigned when his relationship with May and her team broke down. “No opposition was brooked at all,” a former Cabinet minister told me. “That was the way they worked.” Two weeks later, May gave her speech at Lancaster House, a splendid Foreign Office residence a few hundred yards from Buckingham Palace, in which she confirmed that she would take Britain out of the bloc’s single market and its customs union. It was a bright winter day. May spoke in the Long Gallery, facing a portrait of Queen Victoria on horseback. She promised to walk away from the Brexit negotiations if they were not to her liking. “No deal for Britain,” she said, “would be better than a bad deal.”

Downing Street is a cul-de-sac, often in shadow, which is squeezed between large government buildings. When you approach the door of No. 10, which gleams like a polished shoe, it swings open at the instant that you are worried it will not. Corridors extend implausibly far for a town house, revealing the dimensions of the structure behind. Earlier this year, I was waiting on a sofa for a meeting when May came walking alone down the hall. She smiled, dipped her head, and hurried on. It was like encountering a bashful neighbor twice in the same afternoon. “She’s not somebody who enjoys the trappings of being Prime Minister,” a former aide said. “She hates it.”

May likes to pick up her own dry cleaning and to go to the supermarket on weekends. She has gone to the same hairdresser, near her house in Sonning, Berkshire, for twenty years. Her schedule makes no accommodation for the fact that she has diabetes, and must inject herself in the stomach with insulin before every meal.

May suppresses her reactions so completely that she can discourage them in other people, too. In early October, 2016, weeks before the U.S. Presidential election, she was briefed at her regular morning meeting about the “Access Hollywood” recording, in which Trump, in 2005, boasted about kissing and groping women. “Grab ’em by the pussy,” he said. “You can do anything.” May, who as Home Secretary introduced national domestic-violence legislation, and who for the past two decades has campaigned for greater female participation in politics, betrayed no response. No one else did, either. “Nothing was said,” an official who was present told me. “We moved on as quickly as possible.” After Trump was elected, he and May exchanged phone calls, which she found to be a struggle. The two could not be more different. “He doesn’t stick to any talking points, and to someone like Theresa May, who is formulaic, she can’t deal with it,” the former staffer told me. But on a visit to the White House, in January, 2017, May successfully challenged Trump—impromptu—to publicly state his support for NATO. “That was outstanding,” the staffer said. “And that just shows a glimpse of the politician: I can be political, I can nail you down.”

In the spring of 2017, May sensed another opportunity. Polls showed the Conservative Party with a twenty-point lead over Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party, which was rudderless and conflicted over Brexit. May is sometimes compared to Tony Blair’s successor, Gordon Brown, another austere, driven figure who entered Downing Street unopposed. In 2007, soon after taking office, Brown decided against holding an election to secure a popular mandate. It turned out to be the peak of his popularity, and his premiership never recovered. May’s team was determined not to repeat the mistake. On April 18th, May announced that she was calling a snap general election to unite the nation behind her plan for Brexit, which she claimed was being undermined by Labour and the other opposition parties. “The country is coming together,” May said. “But Westminster is not.”

Although May had called the election to settle Brexit, she launched her campaign, a month later, with an arcane reform of social care for the elderly. The rest of the manifesto, which had been written largely by Timothy, was similarly uninspiring. On camera, May was uneasy and dour; the press called her the Maybot. After the launch, officials at Party headquarters watched a ten-point lead in their internal polling disappear in four days. “I have never seen anything like it,” the former Party official said. While Corbyn enjoyed being on the road, and his policies—aimed at increased government spending—caught the mood of a nation fed up with seven years of austerity, May stuck rigidly to her script. On Election Night, the Conservatives lost thirteen M.P.s, Labour gained thirty, and May’s gamble produced a hung Parliament. She clung to office, but Timothy and Hill resigned.

The Brexit negotiations began eleven days later. Instead of travelling to Brussels buoyed by an election win, May’s government was weak and fragmented. In the aftermath of the election, Dexeu had lost two of its four ministers: one resigned, the other was fired. A photograph from the second day of the talks, at the European Commission’s headquarters, showed the E.U.’s negotiating team, led by Michel Barnier, a former French Foreign Affairs Minister, facing David Davis, May’s Brexit Secretary, and a pair of British officials across a pale-green glass table. The E.U.’s side was covered with papers; the Brits had a single, slender notebook among them.

The first subject of the talks was how the negotiations would be structured: the U.K. wanted to discuss the nation’s exit from the E.U. in parallel with its future relationship, to allow trade-offs between the two. The E.U. refused, insisting that Britain’s withdrawal must be finalized before it would consider anything else. The sequencing of the talks, alongside the ticking clock of Article 50, added to the E.U.’s leverage, which it has used to delay and extract concessions ever since. After a year of negotiations, Britain’s withdrawal has still not been formally agreed; it is stuck mainly on the question of the Irish border and customs arrangements. Discussions on the “future framework” for the two-hundred-and-ninety-billion-pound trading relationship between the two sides began only this May. “I have lots of friends on the other side of the table,” a former British official in Brussels told me. “But they are fairly ruthless negotiators, and they are fucking us over.”

May has meetings about Brexit almost every day. It is not how she would choose to spend her premiership. “There is a cruel irony in this, in that she does have stuff that she wants to do,” a former adviser said. “But she is probably not going to be able to do it.” When May seeks to address something else in British public life, Brexit is usually present anyway.

In June, at the Royal Free Hospital, in North London, I watched May speak to doctors, charity leaders, and politicians about the future of the National Health Service. The N.H.S. is celebrating its seventieth anniversary this summer, but the system is creaking under financial pressure and the needs of Britain’s aging population. Last winter, hospitals throughout the country were forced to turn away non-emergency patients and to cancel thousands of routine operations. During her speech, May promised an extra twenty billion pounds for the health service by 2023. It should have been a good news day. But the announcement was undermined by a disagreement about where the money would come from. Since the referendum, Brexiteers, led by Johnson, have argued that Britain will now be able to spend its annual E.U. budget contribution—last year, it was thirteen billion pounds—on the nation’s schools and hospitals. According to the U.K.’s Office for Budget Responsibility, however, the costs of Brexit to the nation’s finances will outweigh the gains.

At the end of May’s speech, a reporter from the BBC asked whether the so-called Brexit dividend was real. May’s voice quickened. Her hands pumped the air quickly, revealing a Frida Kahlo bracelet. “There will be money coming back from the E.U.,” she insisted. I was sitting a couple of seats away from Suzanne Tyler, a director of the Royal College of Midwives. Around fifteen hundred E.U.-trained midwives currently work in British hospitals, but since 2016 the number coming from Europe each year has fallen by eighty-eight per cent. There is no agreement on the terms under which E.U. midwives will be able to work after March; two hundred and thirty-four left the country last year. “People are uncertain about what will happen,” Tyler told me. “We could lose ten hospitals’ worth of midwives at a fell swoop.”

Seen from Brussels, Britain since the referendum has often resembled a country on the verge of a nervous breakdown. “Look through the papers. Look in the government and the politics, it is only about Brexit,” Guy Verhofstadt, the European Parliament’s Brexit coördinator and a former Prime Minister of Belgium, told me in his office last month. “Brexit, Brexit, Brexit. Can you imagine a country that, for years, the clock stops?” Earlier in the week, Verhofstadt had been in London, pitching May and David Davis his own idea—an “association agreement” with the E.U., loosely modelled on its relationships with Iceland, Norway, and Lichtenstein, which are members of the European Economic Area, or E.E.A. But it hadn’t gone well. “They are still in the idea, I think, that ‘Let’s do a little bit of cherry-picking of the advantages of the union without having the duties,’ ” Verhofstadt said. He put the chances of the Brexit talks collapsing at one in three.

One of the central difficulties of coming to an agreement is the different way that the two sides imagine politics. The Lisbon Treaty, which serves as the E.U.’s constitution, is two hundred and seventy-one pages long; the U.K. has no such thing. In Westminster, no situation is completely unfixable; the rules can be made to bend. For this reason, Brexiteers have always believed that Britain’s economic and military importance to the E.U. would prompt it—or, rather, its German car manufacturers, or its Dutch oil refiners—to offer the nation a singularly advantageous deal. (May often talks about a “bespoke” Brexit.) But, since the vote in 2016, the E.U. has maintained that Britain can choose only from a menu of trading relationships that already exist. “I explained that to May,” Verhofstadt said. “I said, You have a problem, you try to solve it. We on the Continent are different. We need first a concept. If we have a concept, then we are going to try and put every problem that we have inside that concept.”

In the talks, the master of conceptual thinking has been Barnier, the E.U.’s chief negotiator. He is sixty-seven, tall and blue-eyed, and stands like a Doric column. He likes to carry a set of PowerPoint slides around, pulling them out of a brown folder to explain, say, the difference between how goods and services are treated under a free-trade deal, or the manner in which the E.U. screens okra and curry leaves at its borders. Barnier’s favorite slide is known as the “steps of doom.” It shows how each of the red lines that May laid out in her early months as Prime Minister is incompatible with the E.U.’s relationships with its nearest neighbors, whether they are the E.E.A. nations and Switzerland, which are in the single market; or Ukraine, which accepts the jurisdiction of the E.C.J. in certain sectors of its economy; or Turkey, which is part of the customs union. At the bottom of Barnier’s steps is a green tick, indicating Britain’s likely resting place, based on its current trajectory in the talks, alongside Canada and South Korea, which both have trade deals with the E.U. but are subject to none of its interlocking regulations.

I was in Brussels for a European Council, a meeting held four or five times a year and attended by the leaders of the twenty-eight member states. Despite the near-total grip of Brexit on British politics, it was barely on the agenda. The anxieties and anger that helped bring about Britain’s departure from the E.U. are common, in one form or another, to all its members, but the manner of their expression in the U.K. has been unique, making the country seem more of an outcast than it is. The meeting was dominated by the bloc’s ongoing migration crisis, which has brought about a strident, populist government in Italy and imperilled Angela Merkel, Germany’s Chancellor and the E.U.’s central figure and protector for the past thirteen years. The unpredictability of voters and the instability of the world make many European politicians somewhat sympathetic toward the U.K.—“For the Brits, this is a terrifying moment,” a senior E.U. official told me—but they have also strengthened their determination to protect the bloc at all costs, and not to fall prey to the same delusions. “There are two kinds of European nations,” Kristian Jensen, the Danish Finance Minister, said last year, referring to Britain’s situation. “There are small nations and there are countries that have not yet realized they are small nations.”

May arrived for the council in the early afternoon. On her way into the meeting, reporters asked her if she was annoyed by the E.U.’s rigid approach to Brexit. May reached for one of her circular replies: “I will be setting out our position for the future. And what I want to be able to do—what I am sure leaders will want to be able to do—is ensure that we can sit down together, that we can negotiate this for the future.”

Before the meeting began, Charles Michel, Belgium’s Prime Minister, surprised May with a gift of a Belgian national soccer shirt with the word “HAZARD” on the back. Belgium was playing England in the World Cup that night, and Eden Hazard is the team’s star, but people couldn’t be sure that May wasn’t being teased. Since the vote in 2016, the bloc frequently meets in “EU27 format”—without the U.K.—including in all Brexit-related discussions. That afternoon and night, May had to sit through almost fourteen hours of talks, as E.U. Presidents and Prime Ministers debated the bloc’s asylum rules and how to stop migrants arriving via the Mediterranean, in order to give a fifteen-minute update on Brexit, to which no one was officially allowed to reply. When the meeting broke up, just after 5 A.M., May emerged, gaunt in the camera lights, and urged the E.U. to accelerate the pace of the talks. The other leaders, led by Macron, celebrated another long night of European solidarity.

A week later, on Friday, July 6th, May summoned her Cabinet to Chequers, the sixteenth-century manor that serves as the Prime Minister’s traditional country residence. For months, tensions had been deepening between May and staunch Brexiteers, who sensed that the Prime Minister was conceding more and more in the negotiations. On June 6th, Davis came close to resigning over the wording of a “backstop option” for Britain’s future relationship with the E.U., should the rest of the talks fail. The following evening, an audio recording of Johnson, speaking at a supposedly private dinner, was leaked to the press. On the tape, Johnson fantasized about what would happen if Trump were leading Brexit: “He’d go in bloody hard. . . . There’d be all sorts of breakdowns, all sorts of chaos. Everyone would think he’d gone mad. But, actually, you might get somewhere.” In Parliament, Jacob Rees-Mogg, the saturnine leader of the Party’s hardcore, Euroskeptic wing, warned that May’s strategy would leave Britain as “a semi-vassal state” of the E.U.

The Cabinet gathered in the great parlor at Chequers. Recently, the country has been enduring a heatwave. According to the Daily Mail, a thermometer on the wall read eighty-one degrees. May unveiled a plan that bowed to the weight of the country’s economic connections to its nearest and largest trading partner. Along with a “common rulebook for goods”—a euphemism for the regulations of the single market—there was to be “a combined customs territory,” which Brexiteers worry may yet turn out to be a euphemism for the customs union, although May insists that it is not. Those who campaigned for Britain to leave the E.U. fear that the country will end up following its rules but with no formal say in how they are devised. At Chequers, however, the Cabinet agreed to May’s plan. Johnson reportedly compared it to a turd. “Luckily,” he said, “we have some expert turd polishers.”

The truce barely lasted until everyone got home. Forty-eight hours after the Chequers summit, May’s government began to come apart. Davis and Johnson gave up their posts, borrowing in their resignation letters from the language of empire and war. That Monday, I spoke to the senior E.U. official. “It’s a moment that should have happened two years ago,” the official said, of May’s late attempt to soften Brexit. But the official stressed that the E.U. still would not accept her plan, which aims somewhere in between a free-trade deal and the more integrated ties of the E.E.A. nations. “The point of departure for the U.K. is ‘We are exceptional,’ ” the official said, sighing. “They don’t understand.”

In recent weeks, May has started to speak more, in order to sell her formulation of Brexit to the nation. After Chequers, she told the House of Commons, “I have listened to every possible idea and every possible version of Brexit. This is the right Brexit.” It is possible that May is finally stepping out with a plan that is sane and moderate but that she has done so too late. In the aftermath of her Cabinet summit, ten ministers and Tory officials have quit, and the Conservative Party’s internal skirmishing has intensified. In a series of parliamentary votes last week, Rees-Mogg’s faction forced May into concessions that will make any further compromises with the E.U. all but impossible. Her government had to rely on a handful of Labour M.P.s to get its votes through. Corbyn has never stood so close to power. I asked the senior official, who is working on Brexit, whether the current moment seemed more vertiginous than usual. “It just permanently feels like that,” he replied. “It just permanently feels like it is out of control.”

Trump arrived in the middle of it all, like a late-season hurricane. He landed at Stansted airport, in Essex; from there, Marine One, escorted by three Marine Corps Ospreys, battered its way thirty miles south, touching down at the U.S. Ambassador’s residence, in Regent’s Park. May had invited Trump to Britain during her meeting with him at the White House, eighteen months ago. After almost two million people signed an online petition objecting to the honor, it was delayed twice and downgraded from a full state visit. The speaker of the House of Commons, John Bercow, refused to allow Trump to address Parliament, citing the body’s “opposition to racism and sexism.”

The President’s schedule was designed to keep him out of the capital as much as possible. Trump had flown in from the NATO summit in Brussels, where he had aired his doubts about May’s new position on Brexit. “The people voted to break it up,” Trump said. “But maybe they’re taking a little bit of a different route. So, I don’t know if that is what they voted for.” That evening, as May took Trump’s hand on the steps of Blenheim Palace before a dinner with C.E.O.s and a trade delegation, an interview with the President appeared in the Sun, in which he questioned whether May’s approach would allow for an independent trade deal between the U.S. and the U.K., and praised Johnson. “I think he would be a great Prime Minister,” Trump said. “I think he’s got what it takes.”

Brexit and Trump are often compared. The disasters that have occurred in two of the world’s oldest democracies stem from similar causes, but they manifest as very different phenomena. The danger posed by Trump is theoretically unlimited, as borderless as his proclivities and the terrifying power of his office. The Brexit vote, by contrast, has traumatized British politics by narrowing it. There is only one concept, and we are putting every problem that we have inside that concept. May’s assignment has been to quell a populist wave, not ride it; to sublimate the contradictory forces within Brexit and to protect the country from itself. “In that sense she is the antithesis of Trump,” the former Cabinet colleague said. “In every single respect, she is the negative.”

May will probably be destroyed by the experience. No one expects her political career to extend past an eventual agreement with the European Union, if it gets that far. “The Conservative Party is a violent place,” one of her former advisers said.

The climax of the Trump visit was a fifty-minute press conference on the lawn at Chequers. The grass was dried out by the heat. The Ospreys were parked in the distance. May delivered some memorized sentences about how her plan would deliver the Brexit that people had voted for. Trump called the Sun interview, which could be streamed on the Internet, “fake news.” He described May as an incredible woman. “Yesterday, I had breakfast, lunch, and dinner with her,” he said. “Then I said, ‘What are we doing tomorrow?’ Which is today. ‘Oh, you’re having breakfast and lunch with Theresa May.’ ” The Prime Minister smiled.

After that, the occasion became fully Trumpian, as the President recalled being in Scotland and predicting Brexit the day before it happened, when in fact he was there the day after. His anxieties about a future Atlantic trade deal—Britain and America are the largest investors in each other’s economies—had apparently dissipated during the morning. “Whatever you do is O.K. with me,” Trump said. “That’s your decision.” It was Brexit, after all, so it was complicated. May chimed in as best she could while the President inveighed against immigration in Europe, refused to take a question from CNN, and criticized Merkel for planning a natural-gas pipeline with Russia, calling it “a tragedy,” “a horrific thing.” Then it was over. Trump walked back to his helicopter to go pick up Melania, who had been lawn-bowling with May’s husband, Philip, in a garden in London; they would then fly to Windsor to have tea with the Queen. May went back to her study.

Sam Knight is a staff writer living in London.

Tags

Who is online

52 visitors

My long-form seed for this weekend is politics and diplomacy at the highest level.

I suppose if one cuts through all the intrigue it boils down to how bad is England going to get hurt. Exit without a agreement or exit with a agreement of sorts. Damned if you do, dammed if you don't. The classical ''no win position''...

Be careful what you wish for.

I wish them good luck.

Foolish leadership and foolish voters.

Probably will not end well.....