A Surgeon So Bad It Was Criminal

Last year, Duntsch was convicted and sentenced to life in prison, becoming the first doctor in the nation to meet such a fate for his practice of medicine.

The pain from the pinched nerve in the back of Jeff Glidewell’s neck had become unbearable.

Every time he’d turn his head a certain way, or drive over bumps in the road, he felt as if jolts of electricity were running through his body. Glidewell, now 54, had been living on disability because of an accident a decade earlier. As the pain grew worse, it became clear his only choice was neurosurgery. He searched Google to find a doctor near his home in suburban Dallas who would accept his Medicare Advantage insurance.

That’s how he came across Dr. Christopher Duntsch in the spring of 2013.

Duntsch seemed impressive, at least on the surface. His CV boasted that he’d earned an M.D. and a Ph.D. from a top spinal surgery program. Glidewell found four- and five-star reviews of Duntsch on Healthgrades and more praise seemingly from patients on Duntsch’s Facebook page. On a link for something called “ Best Docs Network ,” Glidewell found a slickly produced video showing Duntsch in his white coat, talking to a happy patient and wearing a surgical mask in an operating room.

There was no way Glidewell could have known from Duntsch’s carefully curated internet presence or from any other information then publicly available that to be Duntsch’s patient was to be in mortal danger.

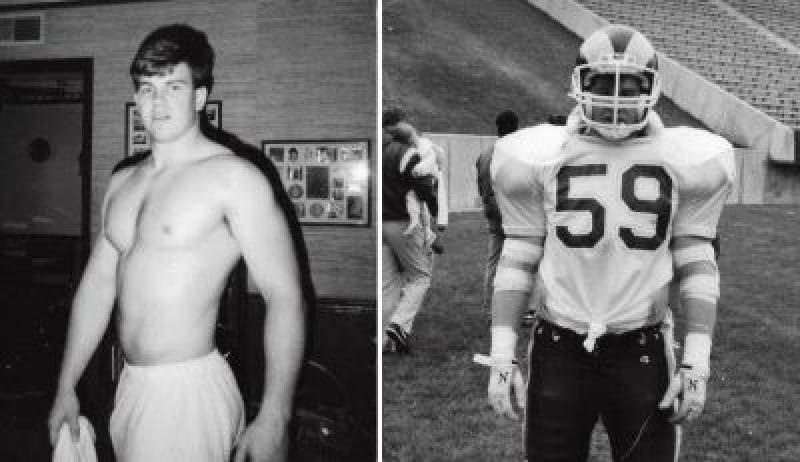

In the roughly two years that Duntsch — a blue-eyed, smooth-talking former college football player — had practiced medicine in Dallas, he had operated on 37 patients. Almost all, 33 to be exact, had been injured during or after these procedures, suffering almost unheard-of complications. Some had permanent nerve damage. Several woke up from surgery unable to move from the neck down or feel one side of their bodies. Two died in the hospital, including a 55-year-old schoolteacher undergoing what was supposed to be a straightforward day surgery.

Multiple layers of safeguards are supposed to protect patients from doctors who are incompetent or dangerous, or to provide them with redress if they are harmed. Duntsch illustrates how easily these defenses can fail, even in egregious cases.

Neurosurgeons are worth millions in revenue for hospitals , so Duntsch was able to get operating privileges at a string of Dallas-area institutions . Once his ineptitude became clear, most chose to spare themselves the hassle and legal exposure of firing him outright and instead let him resign, reputation intact.

At least two facilities that quietly dumped Duntsch failed to report him to a database run by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that’s supposed to act as a clearinghouse for information on problem practitioners, warning potential employers about their histories.

“It seems to be the custom and practice,” said Kay Van Wey, a Dallas plaintiff’s attorney who came to represent 14 of Duntsch’s patients. “Kick the can down the road and protect yourself first, and protect the doctor second and make it be somebody else’s problem.”

It took more than six months and multiple catastrophic surgeries before anyone reported Duntsch to the state medical board, which can suspend or revoke a doctor’s license. Then it took almost another year for the board to investigate, with Duntsch operating all the while.

When Duntsch’s patients tried to sue him for malpractice, many found it almost impossible to find attorneys. Since Texas enacted tort reform in 2003, reducing the amount of damages plaintiffs could win, the number of malpractice payouts per year has dropped by more than half.

Duntsch’s attorney did not allow him to be interviewed for this story. Representatives from one hospital where he worked also would not respond to questions. Two more facilities said they could not comment on Duntsch because their management has changed since he was there, and a fourth has closed.

In the end, it fell to the criminal justice system, not the medical system, to wring out a measure of accountability for Duntsch’s malpractice.

In July 2015, Duntsch was arrested and Dallas prosecutors charged him with one count of injury to an elderly person and five counts of assault , all stemming from his work on patients.

The case was covered intensely by local and state media outlets. D Magazine, Dallas’ monthly glossy, published a cover story in 2016 with the headline “ Dr. Death ”; the nickname stuck.

Last year, Duntsch was convicted and sentenced to life in prison, becoming the first doctor in the nation to meet such a fate for his practice of medicine.

“The medical community system has a problem,” Assistant District Attorney Stephanie Martin said in a press conference after the verdict. “But we were able to solve it in the criminal courthouse.”

Glidewell was the last patient Duntsch operated on before being stripped of his license to practice medicine.

Jeff Glidewell had surgery with Dr. Christopher Duntsch in 2013. He was Duntsch’s last patient, and his call to a judge in early 2015 helped bring the case back to the DA’s attention. (Dylan Hollingsworth for ProPublica)

According to doctors who reviewed the case, Duntsch mistook part of his neck muscle for a tumor and abandoned the operation midway through — after cutting into Glidewell’s vocal cords, puncturing an artery, slicing a hole in his esophagus, stuffing a sponge into the wound and then sewing Glidewell up, sponge and all.

Glidewell spent four days in intensive care and endured months of rehabilitation for the wound to his esophagus. To this day, he can only eat food in small bites and has nerve damage. “He still has numbness in his hand and in his arm,” said his wife, Robin. “He basically can’t really feel things when he’s holding them in his fingers.”

Neither Glidewell, nor the prosecutors, nor even Duntsch’s own attorneys said they thought his outlandish case had been a wake-up call for the system that polices doctors, however.

“Nothing has changed from when I picked Duntsch to do my surgery,” Glidewell said. “The public is still limited to the research they can do on a doctor.”

There is quite a bit more to this story at the link, all of it interesting. I thought it was too long to seed the whole thing here.