The Economics of Donald J. Keynes

What I didn’t realize at the time was just how much bigger the deficits would get. Since 2016, the Trump administration has, in practice, implemented the kind of huge fiscal stimulus followers of John Maynard Keynes pleaded for when unemployment was high — but Republicans blocked.

Contrary to what Donald Trump and his supporters claim, we are not seeing an unprecedented boom. The U.S. economy grew 3.2 percent over the past year, a growth rate we haven’t seen since … 2015. Employment has been growing steadily since 2010, with no break in the trend after 2016. Still, the long stretch of growth has pushed the unemployment rate down to levels not seen in decades. How did that happen, and what does it tell us?

The strength of the economy doesn’t reflect a turnaround of the U.S. trade deficit, which remains high. Nor does it reflect a giant boom in business investment, which proponents of the 2017 tax cut promised, but didn’t happen. What’s driving the economy now is, instead, deficit spending.

Economists often use the cyclically adjusted budget deficit — an estimate of what the deficit would be at full employment — as a rough measure of how much fiscal stimulus the government is providing. By that measure, the federal government is now pumping as much money into the economy as it was seven years ago, when the unemployment rate was more than 8 percent.

The explosion of the budget deficit isn’t just a result of that tax cut. After Republicans took control of the House in 2010, they forced the federal government into austerity, squeezing spending despite high unemployment and low borrowing costs. But once Trump was in the White House, spending was suddenly O.K. again (as long as it didn’t help poor people). In particular, real discretionary spending — expenditures other than those on Social Security, Medicare and other safety net programs — has surged after years of decline.

So there’s really no mystery about the economy’s continuing strength: It’s a Keynesian thing. But what do we learn from the experience?

Politically, we’ve learned that the G.O.P. is deeply hypocritical. After all that Obama-era shrieking about the dangers of debt and the looming threat of inflation, the party cheerfully opened the spigots as soon as it had its own man in the White House. You still see news reports that describe prominent Republicans as “deficit hawks,” and puzzle over their relaxed attitude toward the current flood of red ink. Come on, everyone knows what that was all about.

Beyond that, we now know that the long period of high unemployment that followed the 2008 financial crisis could easily have been avoided. Those of us who warned from the beginning that the Obama stimulus was too small and short-lived, and that austerity was hobbling the recovery, were right. If we had been willing to provide the same kind of fiscal support in 2013 that we’re providing now, unemployment that year would probably have been under 6 percent, not 7.4 percent.

But at the time, what I used to call the Very Serious People offered many reasons we couldn’t do what textbook economics said we should be doing. The V.S.P. said there was a debt crisis, even though the U.S. government was able to borrow at incredibly low interest rates. They said high unemployment was “structural,” and couldn’t be solved by increasing demand. In particular, workers didn’t have the skills needed for a modern economy.

None of these claims were true. But together with Republican obstructionism, they helped postpone a return to full employment for many years.

So are the Trump deficits a good thing? It turns out that two years ago the U.S. was further from full employment than most people thought, so there is a case for fiscal stimulus even now. And the risks of debt are far lower than the Very Serious People claimed.

If we’re going to run up debt, however, it should be for a good purpose. We could be using deficits to rebuild our creaking infrastructure. We could be investing in children, making sure they have adequate health care and nutrition, and lifting them out of poverty.

But Republicans are still blocking any kind of useful spending. Not only are Senate Republicans opposed to infrastructure investment, the Trump administration is proposing big cuts in aid to children, especially health care and education. Deficits are apparently good only if they’re incurred giving huge tax breaks to corporations, which use the money to buy back their stock.

So that’s the story of the economy in 2019. Employment is high and unemployment low, because Republicans have embraced the kind of deficit spending they claimed would destroy America when Democrats held power. But none of that spending is being used to help those in need, or make us stronger in the long run.

There are lots of documenting links in the OA.

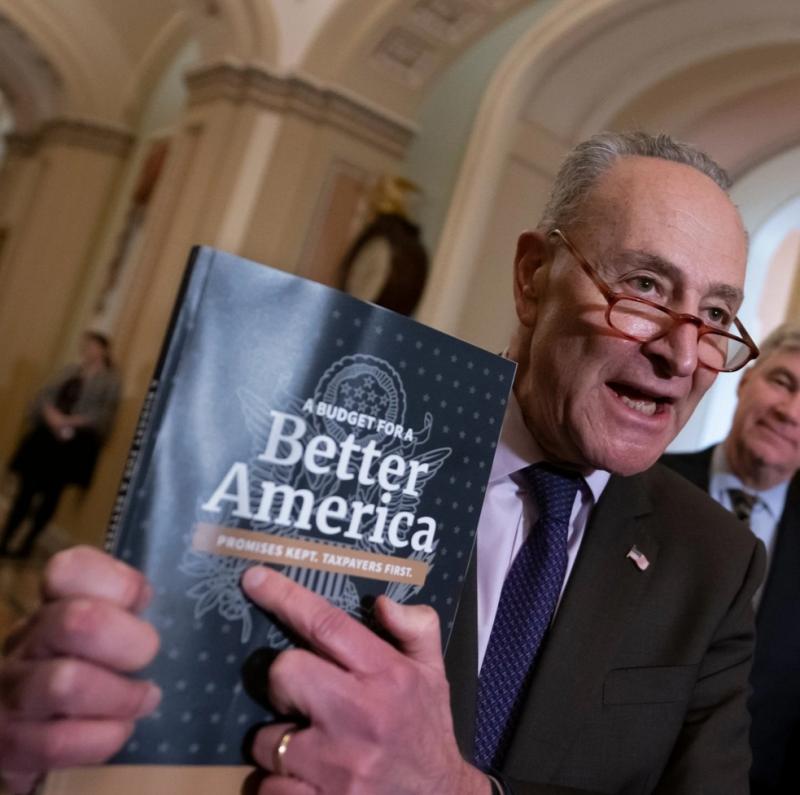

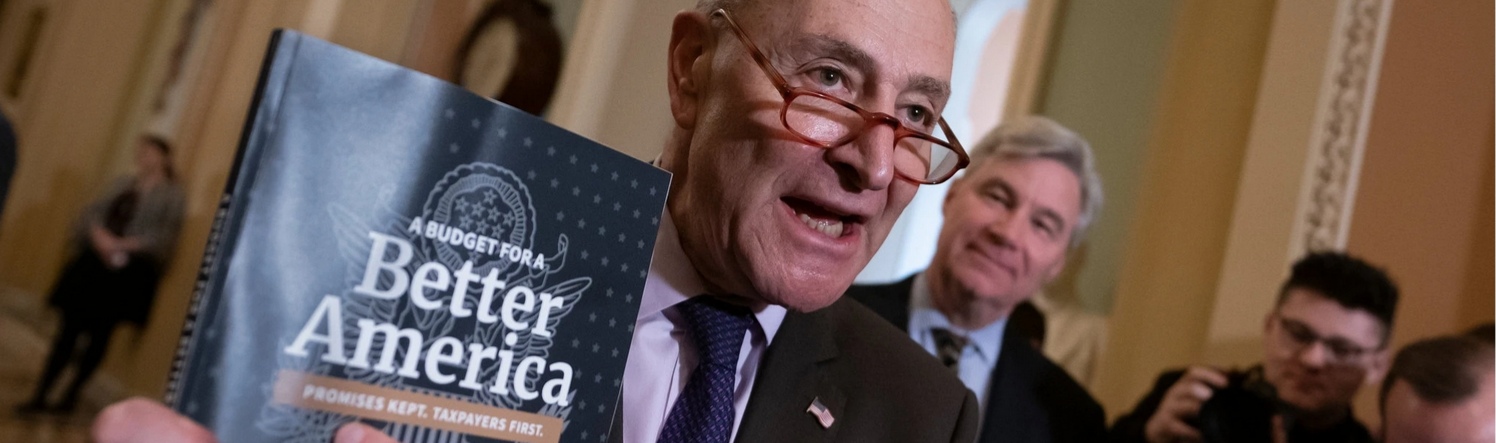

Initial image: Senator Chuck Schumer speaking about President Trump’s budget plan in March. J. Scott Applewhite/Associated Press

From Krugman's blog today: