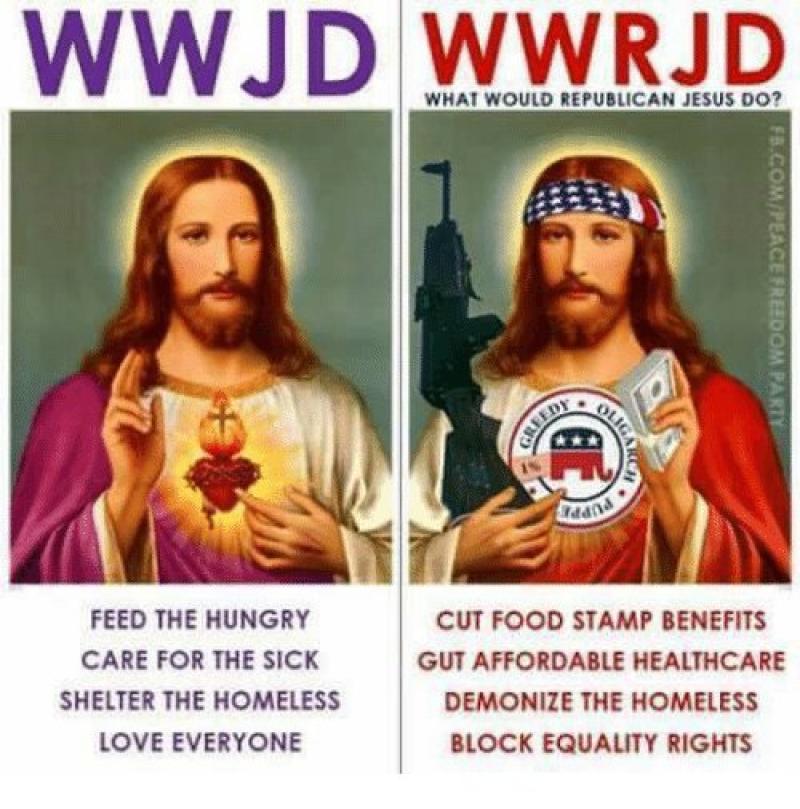

‘So heavenly minded you’re no earthly good’

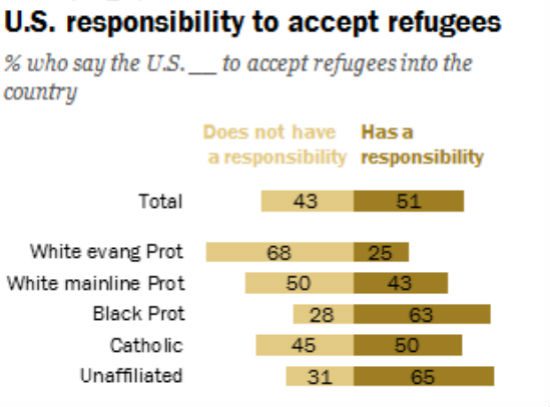

Partisanship and ideology are major factors in opinion about whether the U.S. has a responsibility to accept refugees. Yet there also are differences by race, age, education and religion. … By more than two-to-one (68% to 25%), white evangelical Protestants say the U.S. does not have a responsibility to accept refugees. Other religious groups are more likely to say the U.S. does have this responsibility. And opinions among religiously unaffiliated adults are nearly the reverse of those of white evangelical Protestants: 65% say the U.S. has a responsibility to accept refugees into the country, while just 31% say it does not.

An overwhelming majority of white evangelicals denies any responsibility for aiding strangers in need. An overwhelming majority of religiously unaffiliated Americans affirms that responsibility.

Therefore, one of these groups, according to the Bible, knows God and abides in God. The other group, according to the Bible, consists of “liars” who do not know God. They do not abide in God and God does not abide in them.

The Bible says this . So, again, it seems that intra ecclesiam nulla salus . If you want to know God — if you want to be saved — then it’s probably best to avoid white evangelical churches.

“Transcendentize” should be a word.

Yes, it would be an obnoxiously ugly word — a clumsy, awkwardly pretentious and high-falutin’ word. It would be the kind of fancy schmancy word that would always inject a note of “ Look at me! Look at me! I’m a smarty pants! ” along with whatever else it was attempting to communicate.

But that’s part of why this unlovely word is needed. Because it’s the necessary counterpart of an existing word for which all of that is also true. And “transcendentizing” is usually what people are doing when they use that other word.

That other word, of course, is “immanentize.” That one has been kicking around in theology and philosophy for more than a century, but it still seems unnaturally stilted. You can still see and hear it being wordified into being every time it’s employed, the haphazard seam of its stitched-on suffix still visible.

“Immanentize” is an unavoidably showy word. It conveys both the sense that the speaker has read and studied lots of theology and/or philosophy and the sense that the speaker wants you to know that. This is part of its appeal, as its often employed as an authoritative sounding word meant to end the conversation. “Don’t immanentize the eschaton” or “you’re immanentizing the transcendent” are both statements with actual meaning and substance, but they are also statements warning that no response will be heard or engaged unless it too rises to this level of extravagantly learned-seeming language.

The awkward verbification “immanentize” is almost always employed negatively, as criticism or a warning against a kind of imbalance. If imbalance in one direction is concerning, then it seems reasonable to conclude that imbalance in the opposite direction should also be concerning. Hence the need for an awkwardly verbified word to describe that opposite imbalance: “transcendentizing.”

This word would also be useful, I think, for describing what it is that many people are doing when they issue their authoritative, conversation-ending decrees against the self-evident danger of “immanentizing.” It’s difficult to warn against that as something dangerous without thereby commending transcendentization. Or transcendentizification. Or transcendentizificationism. Or …

You know what? Instead of verbifying another ugly new word into existence, let’s just fall back on some older, simpler words strung together in a bit of time-honored folk wisdom: “Don’t be so heavenly minded that you’re no earthly good.”

Or we could revisit some even older, plainer, and blunter language, from the author of 1 John. Because, again, this is right there in the Bible :

Beloved, let us love one another, because love is from God; everyone who loves is born of God and knows God. Whoever does not love does not know God, for God is love. … Those who say, “I love God,” and hate their brothers or sisters, are liars; for those who do not love a brother or sister whom they have seen, cannot love God whom they have not seen.

That’s canon. It’s holy writ. It’s unambiguous and uncomplicated and as plain-spoken and straightforward as can be. “Whoever does not love does not know God.”

Recite that or show any sign of taking it seriously — as theology or philosophy, as ethics or as epistemology, as religion or as politics — and the transcendentizers will soon show up to condemn you for immanentizing. They’re so heavenly minded that they’re no earthly good.

And they do not know God, for God is love.

Jesus's straight and narrow path ("love one another") is really, really hard to follow. So lots of people duck and weave, hoping God won't notice. ... ... good luck with that...

One technique is to ignore His very simple message, and instead make up crazy stuff like virgin birth, transubstantiation, and ... well you get the idea. That way they can argue about crap that Jesus never mentioned 'cause He was busy preaching "love"... and they avoid the tough stuff.

Of course... they have to make themselves deaf to Christ's message.

An overwhelming majority of white evangelicals denies any responsibility for aiding strangers in need.

Although I believe this to be a part of the Gospels, perhaps it was omitted from their printing of the Good Book:

The parable of the Good Samaritan is a parable told by Jesus in the Gospel of Luke. It is about a traveller who is stripped of clothing, beaten, and left half dead alongside the road. ... Finally, a Samaritan happens upon the traveller. Samaritans and Jews despised each other, but the Samaritan helps the injured man.

Or just in case they skipped that particular passage.

The Good Samaritan is probably the best known of Jesus's parables, and for reason. It's a story that works at several levels, depending on the audience. Even small children understand the "kindness to a stranger" element, while a lot more sophistication is needed in order to understand the consequences of the relative stations of a Jew and a Samaritan in those times.

Americans would understand it better if it was situated in 1930s Alabama, the victim was a White lawyer, and the Samaritan was a cotton-pickin' nigger.

Always take a walk in the other persons shoes, you may gain a bit of insight.

I'm a fan of His parables. Good stories with inescapable lessons.

Fairly much the ABC's of living a humane life for the most part.

Source? Because I have seen multiple sources that indicate the opposite.

Evangelicals Give More to Charity, Study Finds

Religious Americans Give More, New Study Finds

Who Gives Most to Charity?

Even a HuffPost atheist had to admit this was true:

Does Evangelical Giving Do the World Good?

It is the opening sentence in the first paragraph of this seed, as to the origin Bob would have to answer.

Fair enough. I didn't make that connection because it wasn't presented as a quotation.

Jesus taught about how people should interact with other people. I don't think he was trying to spread concepts of good government. He wasn't trying to be a political scientist. No political party is going to neatly line up with Jesus because he wasn't political.

Religious Republicans may not want government to take their tax money for entitlements and benefits, but they do tend to personally give of their own time and money to charity.

If the US federal government had a track record of effective use of tax revenue where, for example, the tax revenue actually enabled people in need (e.g. providing a safety net and a program to 'teach a man to fish') and not so much despicable waste and corruption, I suspect there would be quite a few who would be more receptive to government administering these programs.

I think that's true, although to be fair, there is plenty of corruption in religious charities, too.

Also, the mere fact that one donates to a charity (religious or secular) does not excuse one from being charitable to the stranger or sojourner. I would guess almost all of us could do more than we do.