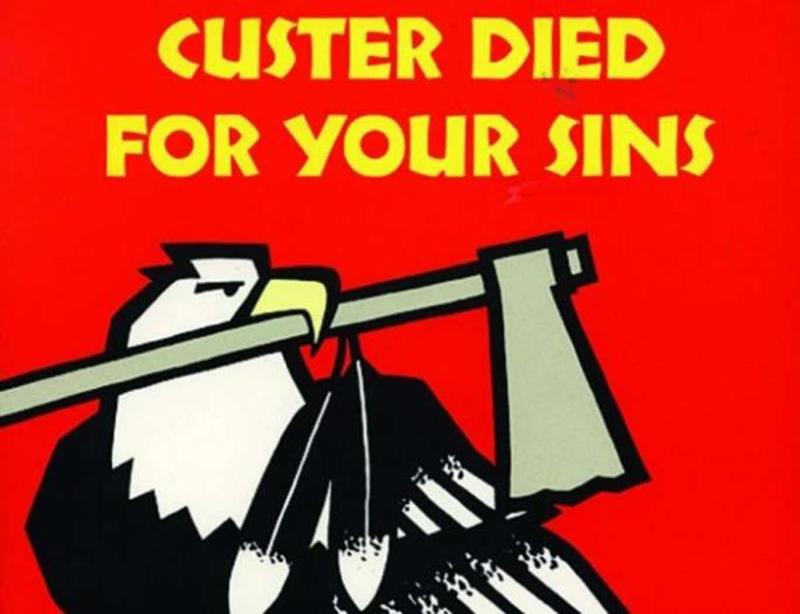

Custer Died For Your Sins, tributes from Indian Country

Fifty-years years ago Vine Deloria, Jr., an enrolled citizen of the Standing Rock Lakota Nation, published Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto. For 1969 mainstream America the title was an attention-grabbing, blasphemous play on the well-known and oft-used Jesus-died-for-your-sins. Deloria took the phrase from a bumper sticker of the same name that he had helped create and said it referred to the bad faith the U.S. demonstrated in failing to fulfill the provisions of the Sioux Treaty of 1868. He explained, “Under the covenants of the Old Testament, breaking a covenant called for a blood sacrifice for atonement. Custer was the blood sacrifice for the United States breaking the Sioux treaty.”

The title was an apt label for a work that excoriated the actions, white-washed history, and on-going racism of the times. Unfortunately, fifty years on, while some of the references and observations are clearly dated, the basic hard truths and embedded injustices continue to underpin today’s Native reality.

Custer was the first of nearly thirty books that Deloria would produce during his singular career. Neither a scholarly work nor a detailed historical account — those would come later — it was rather a deeply personal, riveting observation of the power and vitality of Indigenous sovereignty, defined as the spiritual, moral, and dynamic cultural force within a Native community infusing its citizens with cultural integrity.

He managed to articulate the concept in a way that made sense for Native peoples politically, legally, and perhaps most importantly, culturally. For Deloria knew that cultural integrity — Native lands, languages, values, and spiritual traditions — was the beating heart of Native sovereignty. And it was that integrity, fully acknowledged, if not always enforced, which was woven throughout the several hundred treaties and other diplomatic accords negotiated and ratified between tribal nations and the United States. His grasp of Native personal and political realities led prominent Pueblo scholar Alfonso Ortiz in a review in 1969 to deem Custer, “the most ambitious and most successful overview of contemporary American Indian affairs and aspirations I have ever read.”

The book’s publication in 1969 coincided with events, personalities, and social movements that were exploding across Indian Country and the United States. Americans in the midst of the Vietnam War knew about the Civil Rights Movement, the fight for women’s rights, the Stonewall riots, Johnson’s War on Poverty, Woodstock, and the Poor People’s Movement, but there was very little popular awareness of Native peoples. And a lot was happening within Indian Country, including the Fish Wars of Washington state led by Billy Frank and Hank Adams, the Alcatraz takeover, and the birth of the American Indian Movement in Minneapolis. Thus, the timing of Custer’s release, coupled with the force of Deloria’s trenchant observations rendered in his trademark sardonic prose, elevated the work and gave it real staying power.

Within the slim volume, Deloria skillfully and often humorously lambasted many of the entrenched myths and stereotypes about Indigenous peoples. He castigated powerful institutions. Anthropologists, with their discipline’s penchant for preying on and profiting from Indigenous communities were singled out. Christian churches were called out for their corrupt actions. The main target was the federal government with its multiple branches, departments, and agencies still devising far too many unprincipled laws and policies deployed with arrogance and disrespect towards Native communities.

Deloria infamously wielded humor as a weapon to level his enemies and humble his friends and this book is a strong early example. The biting tone, leavened by his personable prose style, was blunt and engaging — destroying the stereotype of the stoic, martyred Indian. In a chapter titled “Indian Humor,” he contended, in fact, that the ability to laugh at ourselves was a critical strategy used to maintain humanity and facilitate community cohesion in the face of harsh policies and ignorant attitudes.

Another critical aspect of the book, and a first for Deloria, was his laudable, if rudimentary, effort to compare and contrast the situation and status of African-Americans and Indigenous peoples, a comparative intellectual engagement that few scholars were then focusing on. Deloria, writing during a turbulent time of consciousness-raising and coalition building when all assumptions were being questioned, was able to scout a path towards common action. Both groups had suffered horrific abuse throughout history — slavery, land dispossession, forced removal, and ever-present demeaning stereotypes — but the tactics used against each had been very different, tailored to feed the demands of the expanding United States economy and population. As he put it, African-Americans had been treated as “draft animals,” while Native peoples had been treated as “wild animals.”

The United States could not have developed without the abuse and sometimes fraudulent appropriation of Indigenous lives and lands and the abuse and horrific treatment of African American lives and labor. These blood sacrifices were deemed necessary for the fulfillment of the myth of manifest destiny and governmental policies and individual actions reflected and enshrined this reality. Natives were to be dominated and coercively assimilated. African Americans were to remain as a continuous source of cheap labor. Elaborate racial identification calculations were codified during these times, including blood quantum membership schemes for Natives and the one-drop rule for African Americans — one equation designed to mathematically extinguish Natives; the other to maintain slavery in perpetuity.

While the times and circumstances are different, this lethal extractive legacy continues — lead in the drinking water of African American communities in Flint, fossil fuel pipelines fouling the land and water in Indian Country, climate change-driven ice melt in the Arctic. All have their origins in the country’s foundational structures built upon the corrupt pillars of slavery and colonialism.

Finally, unlike other books that merely described historical events or lamented past tragedies, Custer still stands out for the incisive and future oriented ideas for reform — both for Native peoples to consider and for the federal and state governments to ponder.

For Natives, he was particularly concerned with strengthening cultural identity and reconnecting to traditional ways. Thus, he encouraged youth to seek out and establish relationships with homeland-based traditional relatives. He also urged tribal governments to adopt policies curbing the racist, exploitative practices of social scientists researching within Indian Country that demeaned and undermined communities. Ever aware of the strength that could be realized through a full-embrace of cultural sovereignty and self-determination, he called for Native lawyers to develop a common law comparable to English common law, but based in broadly shared Indigenous values and principles.

Deloria also had suggestions for the federal government. He was adamant that Congress needed to codify a policy mandating respect for the inherent sovereignty and dignity of Native people, a “cultural leave-us-alone agreement, in spirit and in fact.” This action was to be accompanied by express legislation acknowledging the sanctity of treaty rights, particularly with regard to subsistence. He also pressed Congress to enact a law to restore lands held by governmental departments to tribal nations. The recent Western Oregon Tribal Fairness Act which restored some lands to four Native nations located within the state’s boundaries is an example on a smaller scale. He was also keen to see a “blanket law” enacted that would have recognized the inherent political status of Eastern Native peoples.

While we are now more familiar with the concept of “restitution,” fifty years ago it was a radical idea. Deloria contended it was vital that Congress initiate a policy of both restitution and restoration of lands that would go far beyond the limited and adversarial scope of the Indian Claims Commission. In his view, until historic claims were justly addressed, it would be impossible to establish more amicable relations between Native nations and the federal and state governments. Fraudulent land transactions and resource misuse — both past and present actions — had to be reckoned with in order for Native nations to meaningfully exercise sovereignty and wield autonomous power.

In 1988, nearly twenty years after Custer was first published, the University of Oklahoma Press smartly offered to republish it, providing Deloria an opportunity to write a new preface. In his opening sentence he wryly noted, “the Indian world has changed so substantially since the first publication … that some things contained in it seem new again” (p.vii). Now, some thirty years later this observation remains true. Until these basic needs are addressed, we will continue to battle symptoms. So, Custer needs to be read yet again — by both Natives and their allies.

As Deloria said in the conclusion of his fresh preface, “the Indian task of keeping an informed public available to assist the tribes in their efforts to survive is never-ending, and so the central message of this book, that Indians are alive, have certain dreams of their own, and are being overrun by the ignorance and the mistaken, misdirected efforts of those who would help them, can never be repeated too often” (p.xiii).

George Armstrong Custer may well have died for the historic sins non-Natives committed against Indigenous nations, but new versions of these sins continue to be abundantly perpetrated today. We know of the outrageous tragedy of murdered and missing Native women, the never-ending attempts to steal Native children from their families, repudiations of the trust relationship and treaty rights, attacks on our relatives the salmon, grizzly bear, wolves and other critical species, the Dakota Access Pipeline debacle, and sacred site desecrations at Bears Ears, the San Francisco Peaks, Oregon's Malheur National Wildlife Refuge and Mauna Kea. We are all now asked to become the blood sacrifices for this corporate-driven federal state, as it seems our very lives are required to feed the next round of extractive and exploitative endeavors.

Vine Deloria, Jr. fought relentlessly to protect and improve the worlds of Indigenous peoples. And, as he saw clearly how the fates of all living peoples and their relatives are bound together, he fought for the Earth, itself. We need his courage, vision, and acerbic wit to get through these dark times. Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto was the first of many hand-sketched maps he left for us as he scouted ahead. We have very little time to band together for our shared survival and, for this battle, we need Deloria more than ever.

David E. Wilkins is professor of American Indian Studies at the University of Minnesota. He is author and editor of numerous books on Indigenous politics and governance. Wilkins is a citizen of the Lumbee Nation of North Carolina.

As Deloria said in the conclusion of his fresh preface, “the Indian task of keeping an informed public available to assist the tribes in their efforts to survive is never-ending, and so the central message of this book, that Indians are alive, have certain dreams of their own, and are being overrun by the ignorance and the mistaken, misdirected efforts of those who would help them, can never be repeated too often” (p.xiii).

I never heard of the book, but I am interested. I have thought about the plight of Native Americans and their noble resistance to being subjugated. A book that stands out in my mind was "Son of the Morning Star". It was a darker moment in American history. Custer dying for our sins? Interesting... and ironic that it was the massacre of the 7th Cavalry that sealed the fate of the Indian tribes - it galvanized the nation!

Believe us Vic - once you get involved in reading this book - you'll be hooked. Vine is one of the best writers pertaining to Native Americans - bar none.

Alright, Your'e on!

Excellent book by Deloria.

Very good book review by Professor Wilkins.

Thank you 1st.

Great review 1st! Thanks for bringing it to us!

I thought it was Christ who died for our sins, not Custer. Still, great seed. I don't read much these days, but I am going to check this book out.

If you're a "Christian", that may be so. If you're a Native American . . . . . . .

I really think you'll enjoy the book Paula. He's even got a "tale" about Cherokee Princesses in it

I am neither so I guess no one will ever die for my sins except for me.

Do you think that I would read the book just because it has a princess in it. I am offended.

That was stated in reference to the many who call Ms. Warren Pocahontas - no reference to you.