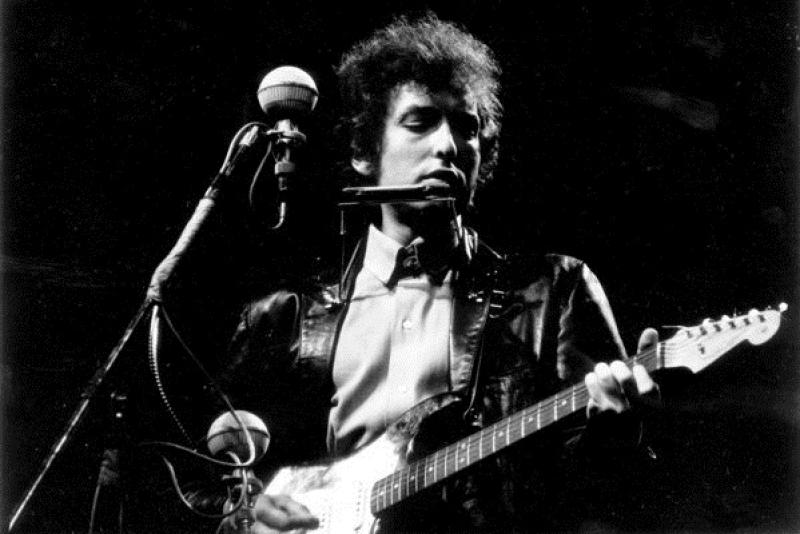

Bob Dylan Goes Electric

Bob Dylan Goes Electric

The 1965 Newport Folk Festival Controversy

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Bob_Dylan_June_23_1978-58e11e2c5f9b58ef7efe9714.jpg)

Chris Hakkens / Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons

The date: July 25, 1965. The event: the Newport Folk Festival. Backed by guitarist Al Cooper and other members of the Paul Butterfield Blues band, along with pianist Berry Goldberg, an earnest 24-year-old Bob Dylan took the stage, an uncommon sight hanging from his shoulder: an electric guitar. The rising star had a major surprise planned for the audience, but he had no clue of the controversy he was about to stir.

The Meltdown

Dylan's performance was innocent enough. Intent on showing off a pocketful of new electric songs, some from his just-released half-acoustic-half-electric album, Bringing it All Back Home, Dylan tore into his music with driven abandon, as he commonly did during acoustic performances. A mix of both cheering and booing started when Dylan launched into “Maggie's Farm,” but the situation continued to melt down as he wound onward through the as-yet-unreleased single, “Like a Rolling Stone.” Finally, the hostility climaxed with chants of “Sellout!” as Dylan ran through “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, it Takes a Train to Cry.” Things got so sensational and warped that a purple-faced Pete Seeger was allegedly running around backstage with an ax, threatening to chop the wires to the soundboard. Enough was enough; after ending the song, the musicians walked off, somewhat stunned. After all, hadn't Muddy Waters played electric at the festival? Why was the audience open-minded and accepting about some musicians, but not about Bob Dylan?

Consider for a second all the facial expressions casting about. All that seriousness. Rage, fury, angst, confusion. Intensity. By all accounts, the vibe was best described as surreal after the musicians left the stage. When lured back out by former stage mate Joan Baez, a shaken Bob Dylan grabbed an acoustic guitar and gave the crowd what it ultimately came for. His return to the stage was pure class. The atmosphere was still tense, but to some modest applause, he assuaged the fold with “Mr. Tambourine Man,” salvaging the day, and soon ending his set with an apropos of everything, “It's All Over Now, Baby Blue.”

A Musical Visionary A-Changin': Folk or Rock 'n' Roll?

By 1964, Bob Dylan was going places, but nobody knew quite where, least of all himself. He had pretty much catalyzed his credentials as an activist in the civil rights movement with his album, The Times They Are A-Changin'. He had already been performing some of the record's songs during civil rights rallies throughout the preceding year in Mississippi. The song “Only a Pawn in their Game” (about the brutal murder of NAACP field secretary Medgar Evers by a Klu Klux Klan member), became emblematic both of the atrocities being committed in the American South, as well as Dylan's growing leadership as the poet laureate of the civil rights movement.

This wasn't necessarily what he had in mind for his musical future. If we've learned one thing about Dylan over the years, it's that he likes to experiment, then move quickly onto the next thing. But in the mid-1960s, during the peak of his creative prowess, some fans didn't understand Dylan's need to keep moving and push the limits of his art. By early 1965, Dylan had already moved on from his good standing as a musician-activist and was writing new songs with an electric band. Meanwhile, his peers in the folk scene were pressuring him continue on as a protest singer that mustered the ranks of American youths to the cause.

He Said, She Said

The entire controversy has been the speculation of theorists and revisionists over the years. Some blame the poor quality of the Newport sound system for the uproar. Others claim the problem was a slapdash performance by an unrehearsed band. In Martin Scorcese's 2005 documentary, No Direction Home, a much-older Pete Seeger (who was partly responsible for bringing Dylan to Newport) was almost apologetic, denying allegations that he was fuming during the performance and threatening to pull the plug, joining the crowd in its angry chant for Dylan to leave the stage. In his autobiography, Backstage Passes and Backstabbing Bastards (1979), Al Kooper swears that the boos had nothing to do with Dylan playing rock music, bad sound quality, or any of that. According to him, it was because Dylan was only going to play 15 minutes, while everyone else played 45; the crowd simply wanted their money's worth.

Whatever the case, a good portion of the audience—or at least the booers—came expecting to hear “The Ballad of Hollis Brown,” “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” and other songs from Dylan's acclaimed repertoire as a “protest singer.” It was one thing to break from that topical mold and start singing personal songs like he did for the 1964 album, Another Side of Bob Dylan. But this electric business was pushing it a little too far.

Dylan's Newport Legacy

To the surprise of many, Dylan actually revisited Newport for a live performance at the folk festival in 2002, and the hype abounded. But if the mucky-mucks expected Dylan to bury some kind of hidden Newport statement in his song choices, they would be denied. Costumed in a phony beard and wig, Dylan started things off with an acoustic “The Roving Gambler”—a common opener on the “Love and Theft” tour—and encored with “Not Fade Away.” Sandwiched in-between was about every song you'd want to hear Dylan perform.

Nowadays critics speculate that had Dylan continued on as an acoustic folk singer and never gone electric, he'd probably never have reached the pinnacle of success that he still enjoys today. But regardless, suffering critical assaults became a mainstay for Dylan after the '65 Newport controversy, and soon afterward the troubadour-turned-folk-rocker would quit performing live altogether for a period of eight years. While Dylan had played Newport—acoustically—in 1963 and again in '64 to much enthusiasm, his conversion to electric was the hardest sell of his career. This festival—once well-known for its hardcore audience of staunch folk purists—would be the showcase for the biggest artistic statement of Dylan's career, an unorthodox and unforgivable blasphemy that will always rank as one of the seminal moments of American rock 'n' roll history.

Although the event was more than half a century ago, I just noticed this article, and posted it because it is about a special event - a milestone in music history - a special memory for me, because....I WAS THERE.

That's cool man.

For whatever reason Dylan decided to go more mainstream. Folk music is a much more niche genre than "rock" , and Dylan became considerably more popular , immediately, than he had been when he was acoustic.

At the time of Newport he had already written and recorded LIKE A ROLLING STONE , which is not a "folk song" nor was the instrumentation of the record folk music instrumentation

In fact , Like A Rolling Stone had been released as a single five days before Dylan went on the stage at Newport.

Today Bob Dylan is an iconic figure in rock history and folk music is still a niche genre. Not that there is anything wrong with that.

Notwithstanding he had already gone electric (and I LIKE his electric renditions) the audience at the Newport FOLK Festival were folkies (including me), not rockers.

By the way, John, could Bruce Langhorne be the best tambourine player? LOL (To all others, that was an "inside" joke).

well he played for mr tambourine man, so i would say so.