History of Violence: Chicago During The Capone Era and Today

Chicagoans and non-Chicagoans alike are familiar with the legacy of Al Capone. The king of crime ruled Chicago’s underworld during the “sinful, ginful” 1920s, and experts say he was responsible, directly or indirectly, for the murders of between 300 and 700 people.

This reputation — combined with all the violence that’s been reported in Chicago lately — got Hyde Park resident Molly Herron wondering about murder numbers and how violence feels to average Chicagoans. So she wrote to Curious City with a question along these lines: How does Chicago’s gang violence today compare to gang warfare under Al Capone?

It’s a good question, because the answer challenges what we think we know about violence and murder in both Capone’s time and ours. Yes, there are crime stats that compare violence in the two eras, but those numbers actually obscure the most interesting points of comparison that stretch almost a century, like how people have been killed, who was targeted, and why.

And, spoiler alert: Both eras are pretty sad.

By the numbers

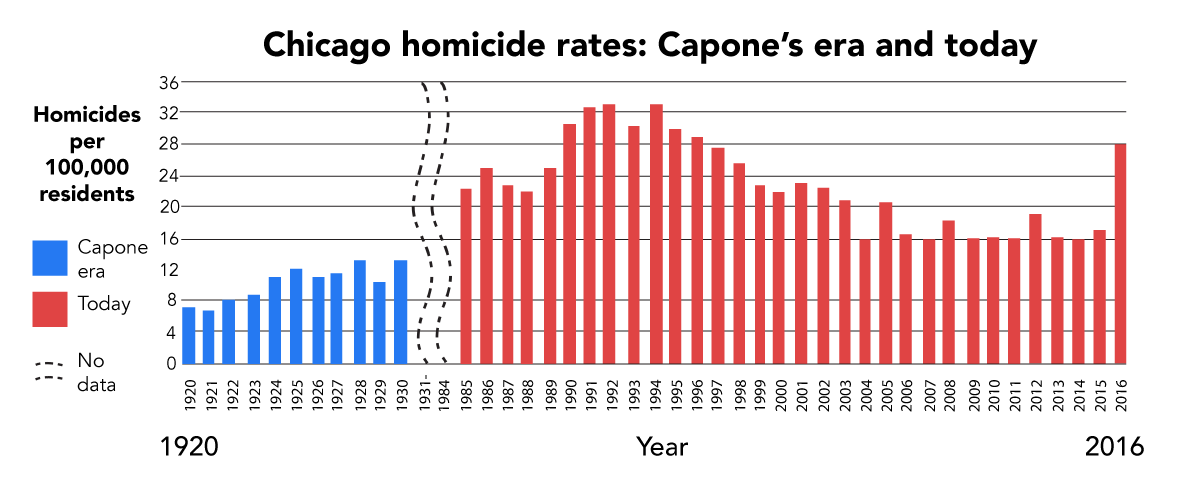

When comparing violence across time in Chicago, there are two reasons to use homicide rates, as opposed to figures such as shootings or “violent crimes.” First, from a legal standpoint, murder is the most serious violent crime. Second, homicides are less likely to go unreported. When someone is killed, there’s a body, and sooner or later someone is going to notice it.

Lastly, homicide rates allow the best apples-to-apples comparisons when adjusting for population. Homicide rates often represent the number of reported homicides per 100,000 residents. That’s important because you’d expect a city with a larger population to have more homicides; what really matters is how many people are killed per a certain portion of the populace. According to Census Bureau records, Capone’s Chicago had about 3.3 million residents, while around 2.7 million residents lived in the city in 2016.

Back to Molly.

Her question implies that violence — murder in particular — in Chicago today is the worst it’s been since, perhaps, the 1920s. And she’s not alone: A good number of people have that impression.

But it’s not true, and here’s how we know.

The period between 1925 to 1931 includes the period when Capone was considered the chieftain of Chicago’s gangland, and it ends with his imprisonment. The average homicide rate during Capone’s reign was about 12 murders per 100,000 residents, according to numbers collected from bulletins of the Chicago Crime Commission and the Illinois Crime Survey of 1929.

Bottom line: The homicide rate was probably lower during the Capone era than in 2016. But it wasn’t much lower than rates seen in the past dozen years or so. It’s also important to point out that murder rates in the Capone era and last year are both lower than rates seen during the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s.

That’s the big picture, but several sources warn against this kind of quantitative comparison — or they suggest taking it with a grain of salt. For one thing, you naturally introduce error when you compare data generated by different agencies. For another, without cross-referencing the historical numbers with coroner’s reports, newspaper articles and state’s attorney’s documents, for example, you can’t do much more than just take those numbers at face value.

That is, the comparison is revealing, but not so precise.

Despite the woolliness involved in comparing Capone-era homicide rates with today’s, though, it’s still useful to compare the two eras when it comes to how people were killed, why they were killed, and who was killed.

What weapons were used?

According to an analysis of Chicago police records by the University of Chicago Crime Lab, 90 percent of Chicago homicides in 2016 involved guns. The crime-related guns recovered most often by the Chicago Police Department were 9mm handguns followed by .44 caliber pistols.

In 1926 the majority of homicides — a little over 70 percent — were committed with guns. But back then, the typical hardware looked a little different.

“The big thing about Al Capone and his gang was they introduced the ‘Tommy gun,’” says Leigh Bienen, director of the Chicago Historical Homicide Project at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law.

Invented for soldiers fighting in World War I, the Thompson submachine gun had a 50-plus-round drum magazine for extended automatic fire. The Tommy gun was Capone’s weapon of choice and became so closely associated with Chicago gang warfare that it was known as the “Chicago typewriter.”

The preferred weapon for close-range shooting was the sawed-off shotgun. Made by sawing off the barrels of a shotgun with a hacksaw, the sawed-off shotgun was not particularly accurate, but at close enough range it didn’t really matter; the gun could blast hinges off doors and eradicate a person’s features.

Beyond guns, the bomb was one of the primary tools used by gangsters, according to the authors of the Illinois Crime Survey. “While the bomb, so far, has proved more bark than bite,” they wrote, “it has done much to confirm and aggravate the bad reputation of Chicago as a gang center and crime-ridden community.”

Although other cities struggled with organized crime during Prohibition, only Chicago seemed to have a bomb problem. Capone had his own bomb squad, and members of gambling and liquor syndicates used dynamite to eliminate their competition, scare enemies, and expose corrupt, adversarial politicians. Fragmentation grenades, which look sort of like pineapples, became so associated with the Chicago Outfit’s (often successful) attempts to rig local elections by intimidating voters that they were nicknamed “Chicago pineapples.”

Why were people killed?

According to the Crime Lab report, most shootings and homicides in 2016 stemmed from “some sort of altercation.” A footnote in the report suggests that most of these altercations take place between members of different street gangs. But as Crime Lab analyst Max Kapustin notes, “altercation” may cover anything from a dispute over drug territory to a revenge killing to an argument turned deadly — so “what that means in practice is anyone’s guess.”

In recent years, a growing share of Chicago’s street violence has been attributed to fracturing gang leadership and frayed relationships between civilians and cops . And there is at least a perception that more violence is being used to settle “petty” disputes — some of which arise over social media . “It’s oftentimes something really simple, like someone sold [drugs] to someone else’s girlfriend or their clothing or whatever,” Kapustin says, but he points out “to [the people committing these acts], it’s not petty. If it’s worth pulling out a gun over, it’s quite serious.”

During the 1920s, the most visible cause of violence in Chicago was organized crime. Alcohol, gambling, prostitution, and extortion were just a few of the rackets Capone was involved in. During Prohibition, alcohol trafficking was lucrative enough that it led to some of the most publicized murders and acts of violence during the conflicts that became known as Chicago’s Beer Wars.

But gangsters didn’t just kill each other over bootlegging territory. One illustrative case is the murder of Joe Howard, a small-time crook with no known gang affiliation.

Howard had been arrested on burglary charges and was known to police as a “dynamiter” — meaning he tossed bombs into liquor establishments if they didn’t pay him money. In 1924, Howard held up Jack Guzik — a sort of fixer and financial manager to Capone — outside a South Side gambling house. During the holdup, Howard said something insulting about Capone, Guzik’s boss. Word got around and Capone — not one to stand for an insult — told one of his guys to go find Howard.

From there, stories diverge. One story has it that Capone’s guy found Howard at a bar, gave him a few drinks, and when Howard was good and drunk, Capone was called and came and shot him. Another is that Capone’s guy shot Howard himself. Either way, Howard ended up dead — all because he called Capone a “pimp.” (Of course, Capone was a pimp; he just didn’t like to be called one.)

Keep in mind that there were plenty of gang murders that had nothing to do with Capone. Even during periods of relative peace between gang leadership in Chicago, underlings and peripheral figures carried out “guerilla wars.” Violence flared-up, too, when political leadership in the city (and so gang protection) shifted.

Leigh says violence was broadly used during the 1920s as a means of “social and political control.”

Who was killed?

On the internet, you’ll find a common trope about how violence in 2016 seems “random” compared to the more “targeted” violence of Capone’s era — a view that Molly had been leaning towards, too. When the Chicago Tribune reported on a January 2016 killing at a Chicago Hyatt hotel , for example, the article’s comment thread (now cleared out) referred to the difference between violence today and during the 1920s. “Chicago saw less blood spilled during the days of Al Capone,” wrote one commenter. Another added, “It was more targeted and less random back then.” A third: “At least they weren’t killing innocent people, they killed who they were after, much more professional.”

When it comes to which era actually had more “targeted” violence, Kapustin says that’s tough to sort out. For one thing, he says, you can’t really know how “random” a homicide is without knowing who the intended target was. In some cases it’s obvious , but in many others, it’s not clear. Without contextual details — which arrive later, if ever — most acts of violence seem random. And, Kapustin says, “even targeted killings are often carried out in a way that is anything but targeted.” And that’s how you end up with bystanders killed .

The takeaway: Evidence suggests both eras experienced targeted as well as non-targeted violence. And, particularly in the Capone era, targeted victims weren’t limited to other “gangsters.”

During the 1920s, violence was targeted, but targeted victims included lawyers, newspaper reporters, police officers, saloon owners, and testifying witnesses. This was in part because organized crime was so intertwined with politics and business in the city.

Take the case of the 1926 murder of William McSwiggin, the assistant state’s attorney who tried, unsuccessfully, to prosecute Capone for the murder of Joe Howard two years earlier. McSwiggin, along with two North Side gangsters, was gunned down outside a Capone-controlled bar called the Pony Inn. There are a couple of theories about what motivated the murder: a territorial execution of the O’Donnell brothers, who had a growing feud with Capone, in which McSwiggin became an unlucky bystander; or a retaliatory slaying against McSwiggin for the case he had aggressively prosecuted against Capone.

When Chicago police did investigate a murder, particularly one thought to be perpetrated by members of a crime syndicate, they hit a powerful wall of silence — a case of so-called “Chicago amnesia.” Gangsters faced a powerful stigma against “rats” and “squealers,” and civilian witnesses were hesitant to testify, lest they be killed. In 1926 and 1927, as reported by the Illinois Crime Survey, Chicago police didn’t solve a single gang murder.

This makes it hard to determine whether victims were directly involved (as, say, peripheral racketeers) or just in the wrong place at the wrong time. There’s evidence to suggest, however, that there were cases of mistaken identity. During the infamous St. Valentine’s Day Massacre , for example, the shooters didn’t kill George “Bugs” Moran, their intended target.

And — although it didn’t happen all that often — bystanders were liable to get caught in the crossfire, just as they are today.

Beyond gangs

Today’s definition of a “gang” or “gangster” is slippery, and it was during the 1920s, too. Kapustin says “the gang landscape today in Chicago is extremely fluid and extremely fractured”— so any determination of gang membership by CPD is “at best going to be off of somewhat outdated, somewhat incomplete information, and at worst very outdated, very incomplete information.”

Even so, in its report on Chicago gun violence, the Crime Lab found that between 2015 and 2016 the percentage of homicides suspected to have been committed by gang members fell, while the percentage committed by non-gang members rose.

Similarly, during the 1920s, a growing portion of crimes were committed outside traditional “gangs.”

The Chicago Taxi Wars, for example, were disputes between employees of two major taxi companies: Yellow Cab and Checkered Cab. Throughout the 1920s, drivers shot at each other’s cars — sometimes while passengers were inside — and the casualties were highly publicized. Ostensibly driven by economic and territorial issues, the Taxi Wars were also personal, as many of the Checkered drivers had been fired by Yellow Cab and held grudges against their former employer.

The public’s lack of faith in law enforcement to solve murders led to vigilante justice and revenge murders. “Private justice was substituted for criminal justice,” a Chicago Tribune reporter wrote in the aftermath of a 1924 killing. That particular story had started with the murder of a cab driver. When the accused assailant appeared in court, the cabbie’s father shot him, purportedly because he had no faith that the assassin would be punished. A writer for Chicago American continued the story: “The slaying in the County Building was a commentary on the cheapness of human life in Cook County.”

As the authors of the Illinois Crime Survey saw it, the most insidious effect of Chicago gang violence of the 1920s was not the dissolution of society into “lawlessness”: It was that the gangster supplanted the legal system of law and order with a system of his own. He used force to accomplish and guarantee trade regulations, to free himself from competition, to resolve conflicts and settle disagreements, to reward his friends and punish his enemies. And other people saw him do it. And simultaneously they saw corruption among judges, abuses by police, and the selfishness of politicians.

These people felt themselves, often rightly, to be disadvantaged in a world that was dead set against them. And they saw the gangster get ahead.

Parting thought: How did the violence feel?

The fact that our questioner, Molly, selected the 1920s as the comparison point — as opposed to, say, the 1980s or 1990s — says something about the way violent crime is covered. Why did she choose the Prohibition period?

“It’s the most violent time I could think of in Chicago history,” she says. As we know, Capone’s era was likely not the city’s most violent, but it’s understandable to connect the two time periods that way. Real violence in both eras — ours and the 1920s — has been sensationalized by the media. “Sure, we have crime here,” said Mayor William Hale Thompson in 1928. “Chicago is just like any other big city … except we print our crime and they don’t.”

In the 1920s most Chicagoans heard about citywide crime through newspapers, which were published about three times daily but focused readers’ attention on just a few dramatized, operatic stories.

It was quite different from today’s coverage, which involves a 24-hour news cycle and an ongoing scroll of Twitter and Facebook posts about the latest shooting or weekend body count.

Compared to the way crime was covered in the 1920s, today’s coverage “makes you feel it’s more pervasive than it is,” says Leigh. “But it also trivializes it, in a weird way.”

I often wonder why Chicago is singled out so much about murder rates. It has rarely had the highest murder rate in the country even among the "major cities". The murder rate in Baltimore for example is usually much higher , as are New Orleans and St Louis and Detroit, and sometimes Miami, and others. I think we have Al Capone and Barack Obama to thank for all the attention to Chicago. Capone because he led his own gang warfare regime in Chicago in the 1920's and made Chicago famous for gang violence, and Obama because he had the nerve to get elected president as a black man from Chicago, thus drawing the attention of those who like to complain about black crime.

But remember, the original Death Wish movies were located in New York and Los Angeles, because that is where the crime waves were in the 70's and 80's and 90's. It's all cyclical.

You know why some seeders focus on Chicago, John.

And they don't even hide why they do it.

Too bad we can't find some shit about Austin, TX or Boston, MA

The gangs do not "run things" in Chicago. [removed]

What did I tell ya, John?

I really do wish I wouldn't see replies to my comments from people I have on ignore.

Why don't you look at the murder rates in those cities and compare them to Chicago?

There were 37 murders in Boston all of last year. Are you really having trouble figuring out why a city with 80 plus murders this month alone gets more attention?

You'll have to speak to the management about that.

As far as what some NT members think about Chicago, there will always be ankle biters going after the big dog.

I've got a couple of gnats buzzing around my head. They're bugging the shit out of me.

I have never been to Chicago. I would like to some day

You'd think when Chicago won the world series in 2016 John would have gotten some congrats but NOoooo, just more degrading seeds. I thought that was really shitty.

That's a glitch. Ask TiG.

Makes me so glad I live out in the middle of the Sonora Desert in SE Arizona. Very few murders with a very small population in my area compared to metropolitan areas.

I have. I don't think it can be fixed.

It's not a problem Pat. This sort of thing goes beyond Newstalkers. Chicago has become a symbol for some sort of dystopian urban area , but it is far from that.

The media is to blame because for sensationalistic purposes they play along with the theme that is presented by the right.

I would like to one day. I have an Aunt and Uncle that lived in the suburbs around the city. He worked in the city.

Eh, anything that is perceived Liberal is going to be attacked.

Never thought I would see the day they are cheering on the feds taking over and basically having marshal law.

I guess they would snatch Ferris Bueller off the street.

the article said something about that, that in Chicago it got the press and it doesn't in other places .

back in the late 70s , early 80s , I knew who the winter hill gang was and who whitey bolger was .

the article also said something about a body , well if its not a drive by and made to look like something like a drug deal gone bad or civil argument its often overlooked from what I saw back then. and that's IF they left a body .

I learned early in life its not hard to take a boat ride out into boston harbor or cape cod bay if the wrong people are crossed .

And I tend not to forget from boston proper , you are less than an hour and a halfs drive from 5 different states and different jurisdictions to dump a body where it likely wont be found let alone identified any time soon.

without the body its simply a missing persons report , and people go missing all the time.

For us a much lighter version took place more recently.

I think we are missing the broad implication of this article. That the structured gang wars during prohibition are somehow just another version of what the crumbling city of Chicago is enduring today. In no way are they similar.

I guess it depends on how you define "major city." Baltimore and St. Louis do have insane murder rates, but neither is even in the Top 30 of most populous cities. Baltimore has a population of less than 700K and St. Louis is about half that. Those cities might have major sports teams and rich histories, but population-wise, they inhabit a different level than truly major cities in the 21st century.

Among cities that have around a million or more residents, Chicago has a substantially higher murder rate than its peers. The murder rate in Chicago is more than twice that of Houston, Dallas, or Phoenix; 3 times that of San Antonio; 3 1/2 times that of Los Angeles; and 6 times that of New York.

No city in the list of Top 25 populations can match Chicago's murder rate. Only Philadelphia is even close. You have to get down to Detroit (about 26th most populous), before you see a higher rate.

I think this matters because people recognize that smaller cities mired in long-term economic and population decline will have higher crime rates because they will naturally have higher concentrations of poverty and desperation. But truly large cities with stable or increasing populations that are more diverse should have a better handle on things.

It's probably made worse by the "nothing to see here" attitude about crime in Chicago that we sometimes get from politicians or news media.

When the accused assailant appeared in court, the cabbie’s father shot him, purportedly because he had no faith that the assassin would be punished.

Another thing to look forward to with the "defund the police" movement...

The big question would be how many of the murders from the 20's involved innocent bystanders or cops as opposed to now?

That may be the real eye opener!

The other thing that makes comparisons hard to make is that people today survive gunshots much more frequently than they did 30 years ago, let alone 90. If treatment of gunshot victims (tons of practice) had remained constant, the homicide rate would be much, much higher today. The skill of first responders has kept the homicide rate in check.

Chicago's mayor has just given in to federal help!

Good article from a historic perspective, I enjoyed it , and how many others started thinking of the 70s hit , the night Chicago died ?