The Cost of Engaging With the Miserable

Category: History & Sociology

Via: hallux • 3 years ago • 6 commentsBy: Charlie Warzel - The Atlantic

Every morning, I wake up and grab my doom machine. My phone is a piece of revolutionary technology that puts the entire world a scroll away, its every pixel an industrial miracle. It’s also a cataclysm-delivery device.

I roll over and click the blue “f” logo to watch older friends and relatives grow angry and entrenched in their politics. I click on Twitter and drown in a torrent of terrible news delivered by shouting messengers. On apps like Citizen, push alerts warn me of violence and petty crimes happening right now in my area, while neighborhood narcs and NIMBYs feud and name-call on Nextdoor.

On the doom machine, feeling helpless and hopeless is easier than ever. Our politics, institutions, and reality itself seem fractured. Perhaps the only salve is to fight on the doom machine over who’s to blame. Inevitably, this makes us feel worse instead of better. So why do we keep doing it? It seems that many of the extremely online are drawn to the doom, and that should make us concerned about the health and future of our public digital spaces.

When journalists and academics talk about the morass of hate and lies online, they tend to focus on tech platforms, rightfully so. The platforms are immensely powerful, and their design can encourage radicalization and the spread of conspiracy theories, amplifying the most toxic forces in our culture.

But online garbage (whether political and scientific misinformation or racist memes) is also created because there’s an audience for it. The internet, after all, is populated by people—billions of them. Their thoughts and impulses and diatribes are grist for the algorithmic content mills. When we talk about engagement, we are talking about them. They—or rather, we—are the ones clicking. We are often the ones telling the platforms, “More of this, please.”

This is a disquieting realization. As the author Richard Seymour writes in his book The Twittering Machine , if social media “confronts us with a string of calamities—addiction, depression, ‘fake news,’ trolls, online mobs, alt-right subcultures—it is only exploiting and magnifying problems that are already socially pervasive.” He goes on, “If we’ve found ourselves addicted to social media, in spite or because of its frequent nastiness … then there is something in us that’s waiting to be addicted.”

Misery, famously, loves company—and, however shallow, social media provides that in droves. It’s worth asking: What if the internet so frequently feels miserable, and makes those of us posting and reacting feel miserable, because so many people are miserable in the first place? What if we all absorb that misery at scale online and, sometimes unwittingly, inflict it on one another?

Misery is measurable. By global standards, Americans are relatively happy. But some indicators are troubling. From 1959 to 2014, the average life expectancy in the United States increased by nine years. Since then, the trend has reversed, and the pandemic led to a sharp decline—life expectancy dropped by a full year in 2020. According to data collected by the Brookings Institution , from 2005 to 2019, an average of 70,000 Americans died annually from “deaths of despair,” such as overdose and suicide. Economic trends show declining social mobility. Mental-health issues are on the rise, especially among young people. The surgeon general warned this month of “devastating” consequences, quoting a 2019 survey that found that “one in three high school students and half of female students reported persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, an overall increase of 40% from 2009.” He cited stressors such as climate change, racial injustice, and income inequality.

What happens when the people gripped by these undercurrents also find a voice online?

Ample evidence suggests that alienated and angry people have built communities around shared grievances. More broadly, millions of Americans feel left behind, under siege, and out of opportunities. The acceptance and fellowship that online communities bring, be they subreddits and Facebook groups or anonymous message boards, allow grievance to harden into a full-fledged identity. Under the influence of true believers and cynical grifters alike, these feelings frequently turn to hate.

Misery is a powerful grouping force. In a famous 1950s study, the social psychologist Stanley Schachter found that when research subjects were told that an upcoming electrical-shock test would be painful, most wished to wait for their test in groups, but most of those who thought the shock would be painless wanted to wait alone. “Misery doesn’t just love any kind of company,” Schachter memorably argued . “It loves only miserable company.”

The internet gives groups the ability not just to express and bond over misery but to inflict it on others—in effect, to transfer their own misery onto those they resent. The most extreme examples come in the form of racist or misogynist harassment campaigns—many led by young white men—such as Gamergate or the hashtag campaigns against Black feminists.

Misery trickles down in subtler ways too. Though the field is still young, studies on social media suggest that emotions are highly contagious on the web. In a review of the science , Harvard’s Amit Goldenberg and Stanford’s James J. Gross note that people “share their personal emotions online in a way that affects not only their own well-being, but also the well-being of others who are connected to them.” Some studies found that positive posts could drive engagement as much as, if not more than, negative ones, but of all the emotions expressed, anger seems to spread furthest and fastest. It tends to “cascade to more users by shares and retweets, enabling quicker distribution to a larger audience.”

Tech executives thought that connecting the world would be an unmitigated good. Widespread internet access and social media have made it far easier for the average person to hear and be heard by many more of his fellow citizens.

But it also means that miserable people, who were previously alienated and isolated, can find one another, says Kevin Munger, an assistant professor at Penn State who studies how platforms shape political and cultural opinions. This may offer them some short-term succor, but it’s not at all clear that weak online connections provide much meaningful emotional support. At the same time, those miserable people can reach the rest of us too. As a result, the average internet user, Munger told me in a recent interview, has more exposure than previous generations to people who, for any number of reasons, are hurting. Are they bringing all of us down?

In an essay titled “ Facebook Is Other People ,” Munger uses one of his relatives as an example. The relative is in his 60s and has a cognitive disability. Munger describes him as “an embittered, lonely man, the perfect target for information fraudsters who will claim to explain that the source of his pain is some despised group (immigrants, the deep state).” The relative has expressed an interest in getting online, and Munger sees only downsides: “His presence as a consumer of online news will have negative consequences, both for himself and for the wider information environment.”

It may sound obvious to say that our digital spaces are not okay because people are not okay. But too many conversations about the problems in online communities elide this fact. They frame the information crisis as solely a technological issue. When Mark Zuckerberg and his fellow tech CEOs come before Congress for their bipartisan grillings, the subtext is that if the companies could only implement the proper moderation policies, remove a few of the most toxic personalities, and change the way content is recommended (according to their desired politics), the problem would go away.

Let’s be clear: Tech platforms have blood on their hands. The leaked Facebook Papers are just the latest evidence of how Facebook’s obsession with growth has exacerbated civic problems globally. Many of the big internet companies have standardized privacy invasions and surveillance as integral to their business model. They’ve accelerated destabilizing political and cultural trends such as QAnon. Facebook and Twitter’s greased, algorithmic rails offer a natural advantage to their most shameless users. The platforms call themselves neutral actors, but they aren’t just exposing our reality; they’re also warping it.

“Our data show that social-media platforms do not merely reflect what is happening in society,” Molly Crockett said recently. She is one of the authors of a Yale study of almost 13 million tweets that found that users who expressed outrage were rewarded with engagement, which made them express yet more outrage. Surprisingly, the study found that politically moderate users were the most susceptible to this feedback loop. “Platforms create incentives that change how users react to political events over time,” Crockett said.

This is the irony of the democratization of speech in action: The platforms don’t just spark unrest and incubate hatred; they also show us a depressing truth about the state of this country offline, independent of technology. In a recent essay , the journalist Joseph Bernstein asked whether social media is “creating new types of people, or simply revealing long-obscured types of people to a segment of the public unaccustomed to seeing them.” Both things can be true.

Technology platforms must be held accountable for their role in our information morass. We need big, structural fixes, including regulation and oversight—though we also have to be careful not to destroy the open internet we cherish.

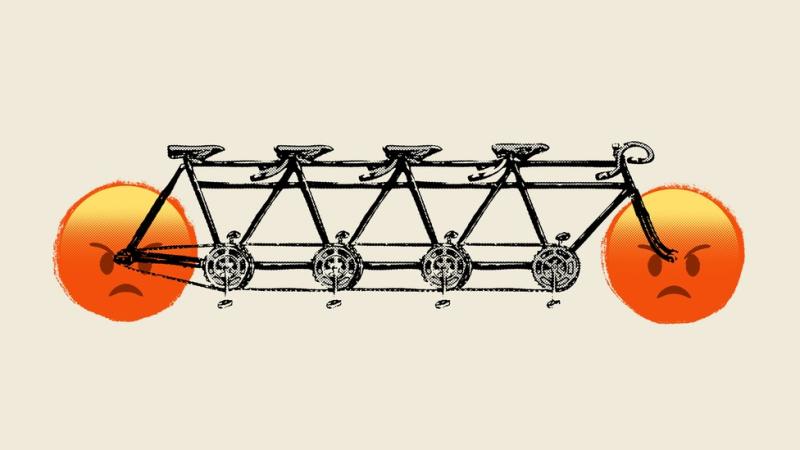

But the technology is only part of the battle. Think of it in terms of supply and demand. The platforms provide the supply (of fighting, trolling, conspiracies, and junk news), but the people—the lost and the miserable and the left-behind—provide the demand. We can reform Facebook and Twitter while also reckoning with what they reveal about the nation’s mental health. We should examine more urgently the deeper forces—inequality, a weak social safety net, a lack of accountability for unchecked corporate power—that have led us here. And we should interrogate how our broken politics drive people to seek out easy, conspiratorial answers. This is a bigger ask than merely regulating technology platforms, because it implicates our entire country.

When I open my doom machine now, I try, as best I can, to see past the abstraction. I try to remember that the internet is powered by real, live people. It’s a frightening thought. But also, maybe, a hopeful one.

Les Misérables? Their cake will poison you.

Avoiding extremist toxicity is a survival technique...

Don't have time for miserable/hateful/ignorant people.

But controlling what is posted over the internet is contrary to the First Amendment, wherein there are so few exceptions, such as the "shouting fire in a crowded theatre" or possibly hate speech if it is serious enough to cause harm. How to reconcile? Has not the internet helped to cause such divisiveness and political polarization in America that it has created two component nations rather than one? Has it not already been aware of the battle between States and the Federal government? It is the extremism that is the worst problem, worse even than just the spread of misinformation and outright lies. The internet can be a benefit for many reasons, and a detriment for others. I know how I feel about it, being a person whose education trained me to seek the real and the true, and that there is almost always another side to a story. Perhaps that is why I have so many times begged Scotty, and then his spirit, to beam me back to the early 1950s.

Was that when you lost your innocence to the wiles and whimsey of a certain Miss Austen?

Yes, my first experience with Jane Austen was when I was 16 in grade 11 when Miss Dixon, our English teacher, had us read P&P and write a review of it. I lost my innocence in the back seat of my father's Hudson Hornet one night in the parking lot of a resort in the Ontario Muskoka Lakes district the following summer - her name was Kitty.