How Paper Money Saved the Union - WSJ

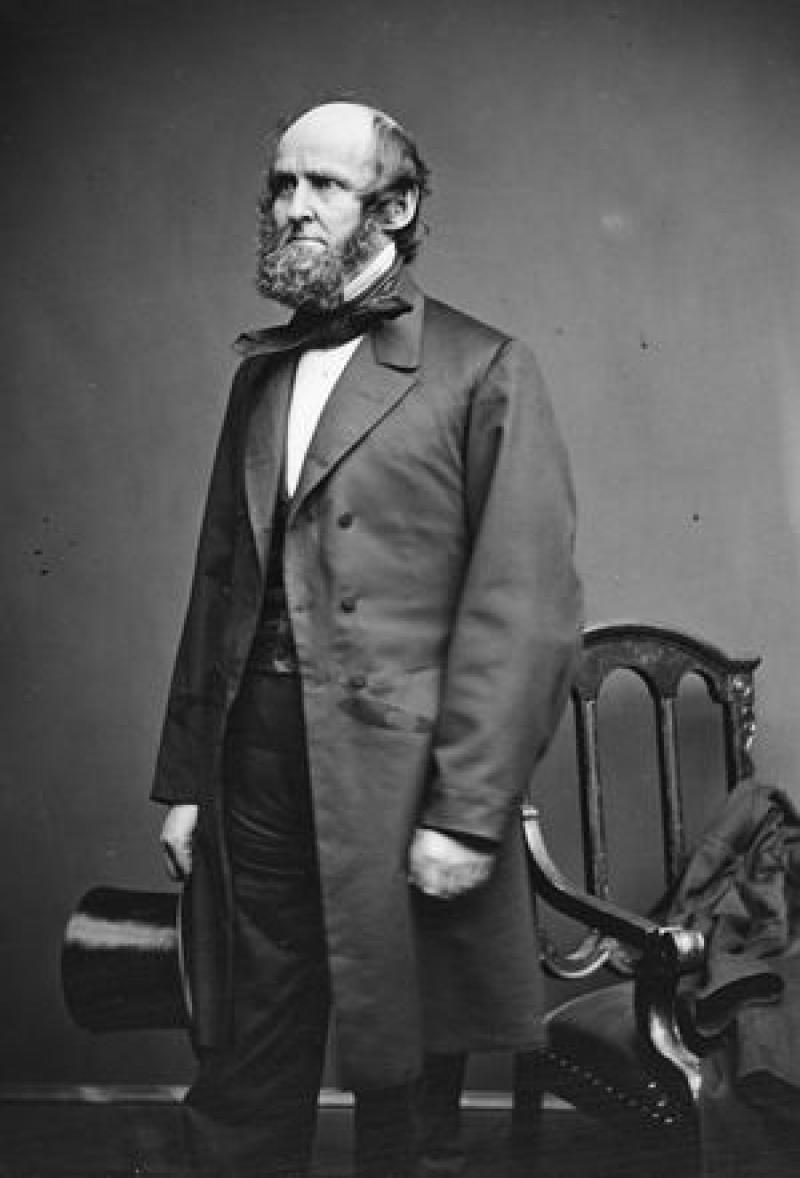

Early in the Civil War, a New York congressman named Elbridge Spaulding had a terrible thought. What if the government were to print pieces of paper and call them money? Paper bills existed, of course, issued by scores of private banks. But they were only IOUs; they had no legal standing. As such, merchants and others could refuse them or mark them down.

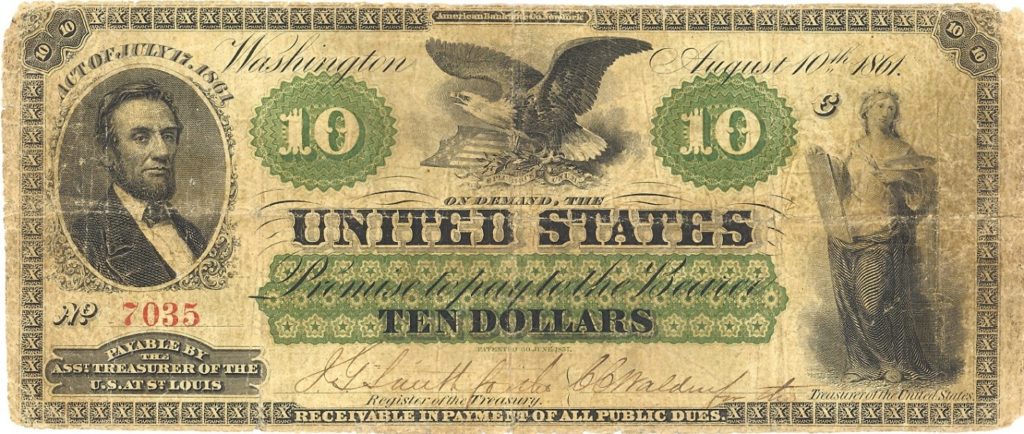

Spaulding meant for his paper to be "legal tender"—valid for all debts and obligations, like gold and silver. It would be paper that none could refuse. This would give the Lincoln government what it desperately needed even more than troops—a currency to pay for the war.

The idea was shocking to his contemporaries. The U.S. had issued Treasury notes, but unlike those, Spaulding’s notes would not pay interest and would not have a maturity date. Today, we scarcely think of the fact that the bills in our wallet do not pay interest—after all, they are “money.” In 1861, referring to paper as “money” was a blasphemy.

The ensuing debate was profound. The Civil War money printers (unlike some central bankers today) agonized over the potential for inflation. They also feared that paper money would jeopardize America’s moral standing. William Fessenden of Maine, the powerful chair of the Senate Finance Committee, said the proposal “shocks all my notions of political, moral and national honor.” Spaulding himself defended his bill as “a measure of necessity, and not of choice.”

But of course, it was a choice. Over the first nine months of the war, the Union had defrayed expenses by borrowing gold. By the end of 1861, the widening conflict had outgrown the capabilities of America’s primitive banking system. The banks, rather than see their reserves depleted, took the alarming step of “suspending”—shutting—the gold window.

From the beginning of 1862 on, the war would be fought with paper. But which paper? Here was Spaulding’s choice.

The banks proposed to lend the government their notes. The Secretary of the Treasury, Salmon P. Chase, insisted on a currency issued by “the people,” not by banks. Since no national currency had existed since the 1830s (when Andrew Jackson had killed off the Second Bank of the United States), the Congress would have to invent one.

The heated question before Congress was: Should the new paper circulate voluntarily, or should it be compulsory for all debts and obligations? Chase, who had an inflated sense of his moral authority, told Spaulding he was “regretting exceedingly” the legal tender designation. Without the Secretary’s endorsement, the bill had no chance.

However, the cost of the war was approaching $2 million per day (nine times the prewar budget). Soldiers and suppliers were going unpaid. Faced with possible bankruptcy, Chase flipped and demanded “immediate action” on legal tender.

Even with Chase on board—and even as thousands of their sons were being slaughtered—legislators were greatly troubled. Objection came from both parties. Rep. George Pendleton, an Ohio Democrat, said legal tender was a “shock” to the mind. Most upsetting, people who had contracted a debt in gold would be able to repay it in paper. According to Rep. Roscoe Conkling, a New York Republican, legal tender would inspire “a saturnalia of fraud; a carnival of rogues. Every agent, attorney, treasurer, trustee, every debtor of a fiduciary character, who has received for others money—hard money…will forever release himself [with] the spurious currency we put afloat.”

Rep. Justin Morrill, a Republican, denounced his party’s bill as “immoral; a breach of the public faith.” Sen. Fessenden agonized that legal tender would discredit America in the eyes of the world. It would sever the dollar from gold, the universal standard in foreign exchange. Britain, the financial center, was on a gold standard, and Fessenden was so sensitive to British opinion (and British trade) that he sent the bill to the Senate floor without recommendation.

Support was greater in the West, where money was scarcer and farmers reflexively favored easier credit. One Westerner who supported the bill was President Lincoln, who looked past constitutional qualms to the plain necessity. As he said to the quartermaster general, Montgomery Meigs, “Chase has no money…The bottom is out of the tub.”

Business interests supported the bill, reckoning that the new paper would stimulate commerce. Still, Fessenden insisted on a compromise that partly undermined it. While legal tender would be a universal money, U.S. bondholders—and they alone—would be paid in coin, a protection to investors, especially overseas, who might shun American credit backed merely by the full faith of a government under siege. Rep. Thaddeus Stevens, a key supporter of legal tender, was apoplectic. He fulminated that the amended bill creates “two classes of currency, one for bankers and brokers, and another for the people.” Lincoln signed it on Feb. 25, 1862.

The new money was instantly popular among soldiers, civilians and merchants. To the dismay of Jefferson Davis, greenbacks, as they came to be called, penetrated deep into Dixie, an early warning sign that the Confederacy was in trouble. A bill for Confederate legal tender was introduced in Richmond, but the rebel Congress was disinclined to so expand the powers of the central State.

Northern traders initially valued greenbacks at 2% less than the equivalent in gold, a discount that widened (at times drastically) according to the ebb and flow of Union armies. As opponents forecast, Congress returned for a second issue of $150 million in 1862, and a third in 1863. By then, inflation was escalating and the Republicans stopped authorizing more.

Wartime inflation totaled 80%, a serious hardship, but never close to the runaway inflation of 9,000% in the Confederacy. The Union’s relative success owed much to Congress’s decision to enact comprehensive federal taxes rather than, as in the South, relying almost exclusively on the printing press. Legal tender gave the country a trusted currency and kept the government afloat at a dire moment. In his memoirs, Sen. John Sherman called the Legal Tender Act the turning point.

After the war, greenbacks were eventually retired, and the nation returned to gold. But the Civil War experience proved to be a foretaste of modern monetary policy. The gold standard was abridged during the Great Depression, and in 1971, President Nixon cut the gold link for good. Since then, the dollar has been fiat money, backed only by faith in the U.S.

One lesson of the original greenbacks was that, because their issue was held to reasonable limits (one-sixth of the war debt), they proved a boon to America’s credit and to the exercise in nation-making that was Lincoln’s ultimate purpose. They gave Americans their own money and were essential to winning the war.

Today, the dollar as a global standard faces threats from nations such as China and from speculative private currencies—unsupported by taxes—such as crypto. The Civil War issuers preserved the dollar’s value, in relative terms, by exercising restraint. The stewards of the dollar today would do well to keep their example in mind.

"Wartime inflation in the Union totaled 80%, a serious hardship, but never close to the runaway inflation of 9,000% in the Confederacy."

—This essay is adapted from Mr. Lowenstein’s new book, “Ways and Means: Lincoln and His Cabinet and the Financing of the Civil War,” which will be published by Penguin Press on March 8.

Something America cannot demonize China for...

The Invention of Paper Money