Whom to believe on Ukraine: Biden, Putin, or Nikolai Gogol?

These days, the speed with which globalised calamities hit the news cycle is vertiginous. We were just learning how to cope with the calamities of Donald Trump’s presidency when the COVID-19 pandemic hit the ground running. The pandemic was still causing havoc around the globe when environmental calamities peaked to frightful dimensions. We had just watched Adam McKay’s apocalyptic black comedy Don’t Look Up (2021) to have a full satirical grasp on our pending climate predicament, when suddenly the headlines became thicker and scarier, warning us that Vladimir Putin was about to invade Ukraine.

Believe it or not, just around that time, I was invited to Moscow for the launch of a new Russian translation of Edward Said’s Orientalism. In the end, I opted to join the gathering via zoom because of the COVID-19 travel restrictions my university had introduced and other obligations that required me to remain in New York. Had I travelled to Moscow, I would likely still be stranded there due to President Joe Biden’s decision to close US skies to Russian aircraft in response to the all-out invasion Putin launched on February 24.

Two weeks on, the Russian army is still in Ukraine, fighting its way towards Kyiv. But to what end? What is this war going to achieve amid a looming climate crisis, a still raging pandemic and massive waves of displacement, famine, death and destruction already devastating the world, from Afghanistan and Yemen to Ethiopia and Myanmar? This reigniting of the nineteenth-century Russian imperial anxieties two decades into the environmental calamities of the twenty-first century really does not make any sense.

‘A plague on both your houses’

So how can we keep our heads above the smoke and breathe an air of sanity?

Personally, I always reach for the same security blanket – enduring works of art, masterpieces of world literature and music – whenever I feel as if the world is spiralling uncontrollably towards Armageddon.

Indeed, if I have to go under, I would rather do so while listening to Shostakovich and Bach, reading Gogol and Hafez, and looking at El Greco and Behzad, with my worn-out copies of YV Mudimbe’s Invention of Africa and Gadamer’s Truth and Method by my bedside.

Today, turning to art is perhaps the only way to sustain inner sanity in an insane world. Over the first two weeks of the Ukraine-Russia war, the propaganda warfare between the United States and Russia has reached a feverish pitch. The habitual liberal Russophobia in the US has been exacerbated by the Trumpian right’s growing admiration for Putin. As Tucker Carlson of Fox News reached new lows in his efforts to defend Putin and his invasion, and the usual suspects at The New York Times started banging the drums of war, we had to seek cover from both liberal Russophobia and conservative declarations of love for a strongman they think can help them restore white supremacy in the US.

The key to remaining sane today is being able to condemn Russia’s bold and vulgar act of military aggression against Ukraine without being sucked into the Anglo-American world’s pathological love-hate relationship with Putin.

It is, of course, not easy to ignore “the West’s” obsession with Putin and exaggeration of his villainy.

When people ranging from seasoned American idiot Thomas Friedman to Israeli best-selling author Yuval Noah Harari come together to argue Putin’s adventurism in Ukraine is unlike anything we have seen before and is a turning point in human history, it is hard not to bury your head in your pillow and wonder where have these people been over the last two decades of US military thuggery around the globe.

Putin after all is not doing in Ukraine anything the US has not already done in Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia and so many other places around the globe – he is simply doing what he is doing not in Asia, Africa or Latin America, but in Europe. Same military thuggery, different bucket.

“Plague on both your houses,” as the Bard famously put it. Why should innocent people in Ukraine, Afghanistan, Iraq, or Yemen pay for imperial arrogance under any flag?

‘We all come out from Gogol’s ‘Overcoat’

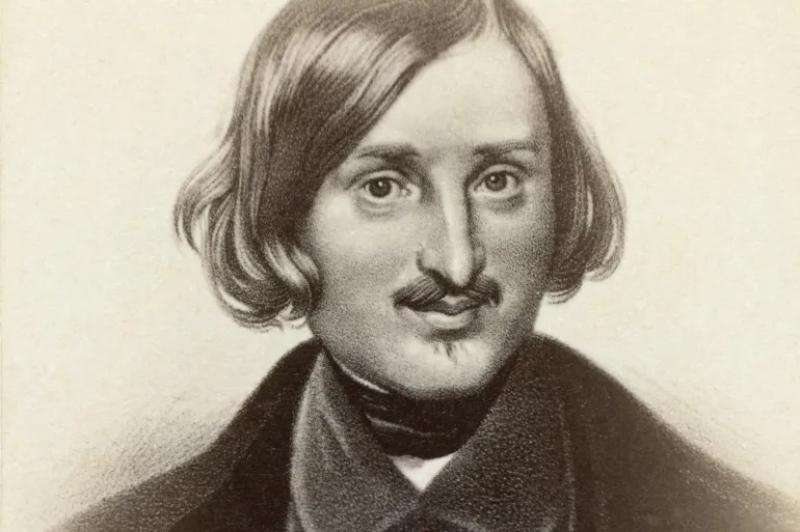

Back to my survival toolkit. In my teenage years, I feasted on Russian and American literature – and never had any taste for European literature bar a few exceptions. Among the towering luminaries of my youthful fascination with Russian literature was and remains the glorious novelist Nikolai Gogol (1809-52). My fascination with him started when I read the Persian translation of his Dead Souls. I became so fascinated with him that I even translated into Persian one of his masterpieces, The Diary of a Madman (which I never dared to publish because I don’t know Russian and felt inadequate doing the translation only from its English translation – in a country where we were blessed with Iranian translators of Russian sources with native fluency over both languages).

For the longest time I had no clue that Gogol was in fact Ukrainian by birth, but Russian by literary culture. And I only remembered this factoid when I found myself listening to Biden and Putin both trying to convince their respective audiences into accepting as fact their own brand of gibberish about the war in Ukraine.

As I watched the two presidents battle for the world’s attention, I couldn’t help but think an entirely different map of the region would emerge if we were to pay attention not to warmongering politicians but to literary history that reveals the inanity of invasion of one country by another.

Consider Gogol’s Taras Bulba (1835), an epic tale chronicling the lives of Cossack warriors. The novel tells the story of an ageing Cossack, Taras Bulba, and his two sons, the younger of which falls in love with a Polish woman. Eventually, that son is captured and shot by his own father. In 1842, Gogol published a second version of this novel in which Russian nationalist themes are more evident. Scholars of Russian literature tell us how this second version of Gogol’s epic novel is actually “the transformation of a Ukrainian tale into a Russian novel” marking the “association of the Cossack and the Russian soul”.

Born in Ukraine, wrote in Russian, read by the world

In an essay they published in 2017, Giorgi Lomsadze and Nikoloz Bezhanishvili offered us a glimpse into the centrality of Gogol in the Ukrainian-Russian borderline of culture and identity.

“Born in Ukraine, made famous in Russia, Gogol embodies both the ties that bind the two countries and the differences that set them apart. As their relations deteriorated, the question of Gogol’s national affiliation repeatedly appeared on a list of matters disputed by Ukraine and Russia.”

What is at stake here? Gogol crossed the borders between his native Ukraine and his literary homeland Russia with ease, grace, and enduring blessing for both his homelands. When at the age of 20 he moved from Ukraine to Russia, he brought the gift of his native homeland to a literary promised land. He joined the ranks of Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, and Turgenev, placing Russian literature on an unrivalled pedestal.

But Gogol was not beholden to Russia either, as he became an iconic literary powerhouse satirising the ruling monarchy. Did any Russian thug tell Gogol, “Go back to where you came from”, as American thugs regularly tell anyone who points out the terror of white supremacist racism in this country? Quite the contrary. “We all came out from Gogol’s Overcoat,” none other than Fyodor Dostoyevsky is reported to have said of one of Gogol’s masterpieces.

In an earlier essay in 2009, Tom Parfitt had detailed the Russian-Ukrainian rivalries in claiming Gogol all for themselves.

“First, it was politics, then it was gas. Now the protracted antagonism between Russia and Ukraine is taking on a literary tinge, as the bickering neighbours vie for the legacy of Nikolai Gogol on the 200th anniversary of his birth.”

But as Russia and Ukraine waged a battle to claim the literary glory of Gogol, people around the world who are neither Russian nor Ukrainian have an equal if not more legitimate love and admiration for Gogol not based on the place of his birth or the language of his literary output, but for the quintessence of his wit, wisdom, and sublime sense of humour.

From the vestiges of the Russian empire emerged the Soviet Union, and from the relics of the Soviet Union survived Russia. Now the traumatic memories of two grand empires, one tsarist, the other communist, haunt Russia’s image of itself. The military follies of Putin in Ukraine are neither the beginning of anything nor the end of something else.

Under Putin, Russia has been active in its own back yard in Chechnya with brutal precision and then in Syria supporting a violent thug on his bloody throne with expanded global ambitions. Neither the jingoism of Russian nationalism, nor the inanities of American pundits thinking this invasion is yet another turn for “the end of history” and civilisation, nor indeed the ghastly European racism once again on full display privileging Ukrainian refugees over millions of others, is the real issue here.

Ceasing to follow the propaganda machinery of Russia and the US, the world would be much better off turning to Gogol, a Ukrainian master of Russian literature, and in the liminal space he crafts in his superior literary heritage, thinking where the real borders lie between civilisation and barbarities.

Lest we get mired in two views, a third to spice it up?

Hamid Dabashi?

Hamid Dabashi is the Hagop Kevorkian Professor of Iranian Studies and Comparative Literature at Columbia University. He received a dual PhD in Sociology of Culture and Islamic Studies from the University of Pennsylvania in 1984, followed by a postdoctoral fellowship at Harvard University. He wrote his dissertation on Max Weber's theory of charismatic authority with Philip Rieff (1922-2006), the most distinguished Freudian cultural critic of his time. Professor Dabashi has taught and delivered lectures in many North American, European, Arab, and Iranian universities. Professor Dabashi has written twenty-five books, edited four, and contributed chapters to many more. He is also the author of over 100 essays, articles and book reviews on subjects ranging from Iranian Studies, medieval and modern Islam, and comparative literature to world cinema and the philosophy of art (trans-aesthetics). His books and articles have been translated into numerous languages, including Japanese, German, French, Spanish, Danish, Russian, Hebrew, Italian, Arabic, Korean, Persian, Portuguese, Polish, Turkish, Urdu and Catalan. His books include Authority in Islam [1989]; Theology of Discontent [1993]; Truth and Narrative [1999]; Close Up: Iranian Cinema, Past, Present, Future [2001]; Staging a Revolution: The Art of Persuasion in the Islamic Republic of Iran [2000]; Masters and Masterpieces of Iranian Cinema [2007]; Iran: A People Interrupted [2007]; and an edited volume, Dreams of a Nation: On Palestinian Cinema[2006]. His most recent work includes Shi’ism: A Religion of Protest (2011), The Arab Spring: The End of Postcolonialism (2012), Corpus Anarchicum: Political Protest, Suicidal Violence, and the Making of the Posthuman Body (2012), The World of Persian Literary Humanism (2012) and Being A Muslim in the World (2013).