Worry Less About Crumbling Roads, More About Crumbling Libraries

Every four years, the American Society for Civil Engineers issues grades for the nation’s infrastructure. In the most recent evaluation , released in 2017, America’s overall infrastructure score was a D+, the same as in 2013. Although seven systems, including hazardous waste and levees, received modestly better grades than in the previous assessment, transit and solid waste, among others, did worse. Aviation (D), roads (D), drinking water (D), and energy (D+), retained their miserably low scores.

The ASCE does not grade our “social infrastructure.” If it did, the scores would be equally shameful. For decades, we’ve neglected the shared spaces that shape our interactions. The consequences of that neglect may be less visible than crumbling bridges and ports, but they’re no less dire.

Social infrastructure is not “social capital”— the concept commonly used to measure people’s relationships and networks—but the physical places that allow bonds to develop. When social infrastructure is robust, it fosters contact, mutual support, and collaboration among friends and neighbors; when degraded, it inhibits social activity, leaving families and individuals to fend for themselves. People forge ties in places that have healthy social infrastructures—not necessarily because they set out to build community, but because when people engage in sustained, recurrent interaction, particularly while doing things they enjoy, relationships—even across ethnic or political lines—inevitably grow.

Public institutions, such as libraries, schools, playgrounds, and athletic fields, are vital parts of the social infrastructure. So too are community gardens and other green spaces that invite people into the public realm. Nonprofit organizations, including churches and civic associations, act as social infrastructure when they have an established physical space where people can assemble, as do regularly scheduled markets for food, clothing, and other consumer goods.

Commercial establishments, such as cafés, diners, barbershops, and bookstores, can also count as social infrastructure, particularly when they operate as what the sociologist Ray Oldenburg called “third spaces,” where people are welcome to congregate regardless of what they’ve purchased.

But if we let public spaces collapse, we can’t rely on commercial establishments to pick up the slack—for the simple reason that people are not always welcome there. Inside almost every fast food restaurant or coffee chain, particularly in racially and socioeconomically diverse neighborhoods, there’s at least one “No Loitering” sign. And it’s not just a suggestion. Consider the recent scandal at a Starbucks in Philadelphia, when baristas called the police simply because two African American men were sitting peacefully at a table while waiting for a friend; or the related incident four years ago in New York City, when McDonald’s forced a group of elderly Korean patrons to vacate less than an hour after they’d ordered. Businesses that discriminate only deepen our divisions.

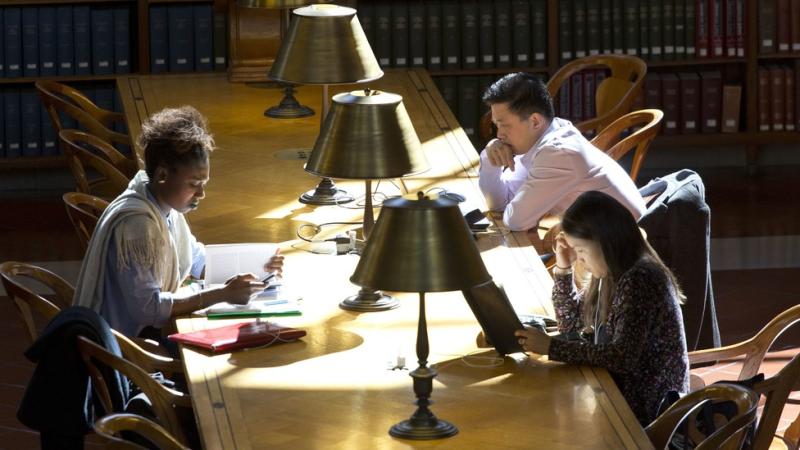

Different kinds of social infrastructure play different roles in the local environment, and support different kinds of social ties. Some places, such as libraries, YMCAs, and schools, provide space for recurring interaction, often programmed, and tend to encourage more durable relationships. Others, such as playgrounds and street markets, tend to support looser connections—but these ties can, and sometimes do, grow more substantial. Countless close friendships between parents, and then entire families, begin because two toddlers visit the same swing set. Basketball players who participate in regular pickup games often befriend people with different political preferences, or with a different ethnic, religious, or class status, and wind up exposed to ideas they wouldn’t likely encounter off the court.

I know from experience. Two decades ago, during my biweekly game in Berkeley, the black, white, and Latino players engaged in a series of long, heated debates about O.J. Simpson’s guilt or innocence. We didn’t necessarily change each other’s opinions about the case, but we gained a far deeper understanding of each other—and our respective group’s experiences—in the process. This surely affected our political perspectives too.

Playgrounds and athletic fields help us connect because they’re places where people linger and talk to strangers. The lingering is crucial; often, efficiency is the enemy. A recent study by the Harvard sociologist Mario Small, for instance, found that a day care center that encouraged parents to walk in and wait for their children, often inside the classroom and generally at the same time, fostered more social connections than one where parents came in on their own schedules and hurried through drop-off and pickup so they could quickly return to their private lives.

It’s extraordinary, Small observed, how quickly parents – even those with different backgrounds – began to trust and support one another when they had a place to gather. Their shared interest in childcare rendered other distinctions secondary, allowing new and meaningful friendships to grow.

Just as certain hard infrastructures, such as those for power and water, are “lifeline systems” that make modern societies possible, so too are certain social infrastructures especially crucial for democratic life. Colonel Francis Wayland Parker, whom John Dewey called the “father of progressive education,” believed that the neighborhood school was a vital space that, when organized properly, served as a “ model home, a complete community, an embryonic democracy .” Schools, Parker and Dewey believed, teach young people not only their roles and responsibilities within the larger and more diverse society, but also the skills and dispositions required to participate as citizens.

Not any school will do, of course. Good schools teach us how to get along; bad schools leave us ill-prepared for the challenges of civic life. In recent decades, too many American states and cities have slashed support for public education. Is it any surprise that our culture now seems more spiteful, and more superficial, than ever before?

In the years I’ve spent observing how shared spaces shape our interactions, the one place that has consistently promoted a modern ideal of mutual respect and enlightenment is the local library. Libraries are not the kinds of institutions that social scientists, policy makers, and community leaders usually bring up when they discuss social capital and how to build it. But they’re among the most critical, and undervalued, forms of social infrastructure that we have.

Whether the libraries I visited were in tony suburbs like Palo Alto, California, cities like Austin, Texas, or small towns like Suffern, New York, I always saw a surprisingly diverse set of people: all ages, different races and ethnicities, a range of social classes and political persuasions. They saw each other, too, and had no choice but to deal with a variety of small shared problems: when to give up a computer to someone who’s waiting, how to deal with an unruly or mentally ill patron, what to do about the shortage of bathrooms. Spending time in social infrastructures requires learning to deal with these differences in a civil manner.

Recently, authoritarian political leaders who understand the power of popular gathering places in their own nations have targeted them for attack. A recent article by the social scientists Brent Eng and José Ciro Martínez showed that in Syria, Bashar al-Assad “has consistently targeted public infrastructures in opposition-held areas, including bakeries, hospitals, markets and schools.” His goal, they explained, is not merely causing physical damage, “but also interrupting and undermining everyday practices” of rebel forces and the communities they’re attempting to organize. Destroying these vital places atomizes and depresses those who want to rebuild a better, more open society. It helps despotism reign.

President Trump obviously hasn’t bombed his domestic enemies, but through proposed funding cuts his administration has indeed attacked the places where Americans of all stripes gather— our libraries , our schools , our parks , our arts and culture organizations . These moves can only deepen our divisions and degrade our public life.

Unfortunately, the federal government’s indifference to our civic institutions mirrors that of state and local governments across America. In New York, for instance, Governor Andrew Cuomo’s budget for 2019 includes a four percent cut in the state library budget . Between 2001 and 2015, Massachusetts cut funding for its Department of Conservation and Recreation by $30 million . These reductions pale in comparison to those made by Republican-controlled states such as Wisconsin, Kansas, and Oklahoma, where governors and state assemblies have made gutting public programs a top priority.

In states both red and blue, our vital systems are crumbling, and so too is our democratic culture. The question before us is what we will do tomorrow. Before we lift the next shovel, we should recognize that what we really need to protect, what we really need to repair, is society itself.

With apologies to the Bard ...

The first thing we do is kill all of the culture warriors be they of the left or of the right.

can we start with the hypocrites first?