My neighbor lived to be 109. This is what I learned from him.

Early one August morning during a heat wave in Kansas City, Mo., I stepped outside to fetch the Sunday newspaper — and something stopped me in my tracks.

My new neighbor was washing a car. In my memory (this detail is a matter of some disagreement around the neighborhood), it was a shiny new Chrysler PT Cruiser, the color of grape soda pop. It belonged to my neighbor’s girlfriend, and I couldn’t help noting that the vehicle in question was parked in the same spot where she had left it the night before. I deduced that a Saturday night date with the glamorous driver had developed into the sort of sleepover that makes a man feel like being especially nice the next morning.

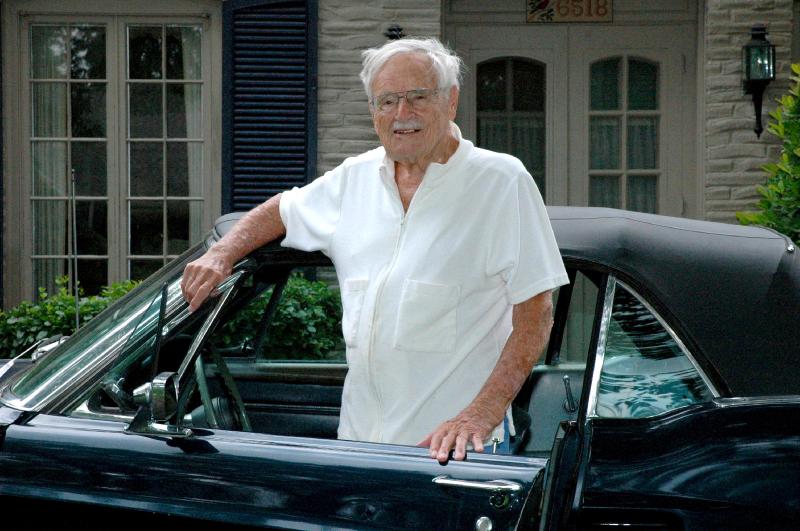

This was Dr. Charlie White. Age 102.

Charlie, I soon learned, was an extraordinary specimen: hale and sturdy, eyes clear, hearing good, mind sharp. His conversation danced easily from topic to topic, from past to present to future and back. Even so, one does not expect, on meeting a man of 102, to be starting — as we did that day — a long and rich friendship.

Actuarial tables have no room for sentiment or wishes, and this is what they say: According to the Social Security Administration, in a random cohort of 100,000 men, only about 350 — fewer than one-half of 1 percent — make it to 102. Among those hardy survivors, the average chap has less than two years remaining. After 104, the lives slip quickly away.

Yet on that muggy Sunday morning, it was clear to me that Charlie wasn’t close to done. In fact, he would live to be 109.

Life seemed somehow to rest more lightly on him than on most of us. I wanted to know the why and the how. As our friendship grew, those questions deepened, for I learned that life had dealt Charlie some heavy blows: grief, victimhood, helplessness, disruption.

I came to realize Charlie was not a survivor. He was a thriver. He did not just live. He lived joyfully. He was like a magnet, pulling me across the street and into his confidences, where I discovered something about life’s essentials. The sort of something one wants to pass on to one’s children.

When my children were young and learned Daddy was a writer of some kind, they began asking me to write a book for them. I wanted very much to deliver, to pull a bit of magic from my hat and spin it into a tale of brave and resourceful young people making their way in a marvelous, dangerous land. But every stab I took at writing a children’s novel failed. Gradually, I saw this would be one more in a catalogue of ways in which I would disappoint them.

Telling Charlie’s story might be my redemption. Although he was not a superhero — no wizards or talking spiders populated his tale — his was a story my children needed. A story many of the world’s children might need.

Today’s children, yours as well as mine, will live out their lives in a maelstrom of change and upheaval. Revolutionary change — which has the power to remake societies, cultures, economies and political systems — can be hopeful and might sound exciting. But it can quickly turn downright scary. For many young people, the future is less a fresh field at dawn than a darkling plain at twilight, ominous and fragile.

Parents of children living through such a time want to give their kids the tools they need. What does it take to live joyfully while experiencing disruption? What are the essential tools for resilience and equanimity through massive dislocation and uncertainty?

That hot August morning, I began to understand that Charlie was the embodiment of this vital information. To my unending gratitude, he welcomed me in, waving hello as his girlfriend’s car sparkled.

Charlie was a physician. He knew how the human body goes — and how it stops. And he was the first to say his extraordinary life span was a fluke of genetics and fortune.

Born Aug. 16, 1905, in Galesburg, Ill., Charlie began life at just the moment that (in the words of Henry Adams) history’s neck was “broken by the sudden irruption of forces totally new.” The setting of his childhood was a world recognizable to farmers from the age of Napoleon. Civil War veterans were a part of daily life, their battles closer to Charlie than Vietnam is to a child born today.

Charlie and the future grew up together. With one foot planted in the age of draft animals and diphtheria — when only 6 percent of Americans graduated from high school, and even middle-class people lived without electricity or running water — Charlie planted the other foot in the age of space stations and robotic surgery.

He lived to be among the last surviving officers of World War II, among the last Americans who could say what it was like to drive an automobile before highways existed, among the last who felt amazement when pictures first moved on a screen. He lived from “ The Birth of a Nation ” to Barack Obama . From women forbidden to vote to women running nations and corporations .

Still, as I’ve reflected on this remarkable friend, I have come to see that he was more than a living history lesson, more than the winner of a genetic Powerball. He was one of the few children of the early 1900s who could tell my children of the 2000s how to thrive while lives and communities, work and worship , families and mores are shaken, inverted, blown up and remade.

Charlie was a true surfer on the sea of change, a case study in how to flourish through any span of years, long or short. Or through any trauma.

For his incredibly long life, I came to understand, was indelibly stamped by a tragically shortened one. He learned early — and never forgot — that the crucial measure of one’s existence is not its length but its depth.

How early? At just 8 years old.

Around 10 a.m. on May 11, 1914, Charlie’s father rose from his desk in the downtown Kansas City office where he worked selling life insurance, donned his coat and hat, and set out on an errand. When he reached the elevator in the corridor — one of the early electric passenger cars — he might have noticed that the usual operator was not at the controls. The door was open. A substitute stood with his hand on the lever.

As my friend’s father moved into the car, the operator unexpectedly put the elevator in motion. The box lurched upward, doors still open. This created an empty space between the unmoving floor of the hallway and the rising floor of the elevator, which was now waist-high. It happened so quickly that instead of stepping into the car, the unlucky man put his foot into the open space beneath.

His upper body pitched onto the elevator’s floor, his legs dangling in the abyss of the shaft. In an instant, the climbing car crushed his torso against the upper door frame so violently that the impact left a dent. Horrified, the inexperienced operator panicked and threw the elevator into reverse. When the compartment lurched downward, Charlie’s father slipped loose, his body following his feet into the shaft, where he plunged nine stories to his death. He was 42 years old.

Over the course of our friendship, I heard Charlie tell this story at least half a dozen times. Not once did he indulge in the sort of “Why, God?” or “What if?” questions that so naturally follow a freak accident. He never remarked on the apparent injustice of a good man’s premature death in a world where history’s most murderous despots — men such as Hitler, Stalin and Mao — had decades of life ahead of them. He never asked: What if an experienced operator had been at the elevator controls? What if my father had set out on his errand five minutes earlier or later?

Yet whenever he talked about his childhood, I noticed a tone shift between the tales of his early, carefree childhood and those that came after his father’s death. In the earlier stories, he was light as a lark. After the tragedy, the boy was armored in self-reliance — as independent as Huckleberry Finn , as resourceful as the Artful Dodger .

As I reflected on this subtle change, it occurred to me that after suffering a loss so enormous, and surviving it, Charlie decided he could get through anything. Brought face to face with the limits of his ability, of anyone’s ability, to master fate or turn back time, Charlie began reaching for the things he could control — his own actions, his own emotions, his outlook, his grit. As he put it: “We didn’t have time to be sad.”

Charlie was not a student of philosophy. Yet in those words, I recognized the essence of a credo that has served human beings for centuries: Stoicism , one of the most durable and useful schools of thought ever devised. It has spoken to paupers and presidents, to emperors and the enslaved. It’s the philosophy of freedom and self-determination, one that seeks to erase envy, resentment, neediness and anxiety. Its pillars are wisdom, courage, temperance and justice. It is a philosophy of radical equality and mutual respect.

Stoicism can be equally as compelling to a grieving boy in the early 20th century as to an abused slave such as Epictetus , who smiled as his sadistic Roman master twisted his leg until it snapped. It teaches that a life well lived requires a deep understanding of what we control and — more difficult — all that lies beyond our control. We govern nothing but our own actions and reactions.

A true education, Epictetus taught, consists of learning that in our power “are will and all acts that depend on the will. Things not in our power are the body, the parts of the body, possessions, parents, brothers, children, country, and generally all with whom we live in society.”

For the enslaved Epictetus, this insight spoke to the resolve to live with purpose and dignity, even as a master controlled his body and actions. He could be bought and sold and worked like an animal, but he could not be made to think or act like an animal.

For the same reasons, Stoicism spoke to Viktor Frankl , an Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist who survived the Nazi slave labor camps. From his observation of prisoners who maintained their self-respect and goodwill even in those hellish circumstances, Frankl concluded that “everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way” of meeting what life presents.

Nelson Mandela was stripped of his freedom by injustice and hatred for more than a quarter-century and emerged from prison stronger than when he went in. “The cell,” he said stoically, “gives you the opportunity to look daily into your entire conduct to overcome the bad and develop whatever is good in you.” What he made of himself inspired the world.

Charlie often counseled his friends and family in times of anger or annoyance: “Let it go.” But the same spirit — which underlies the qualities we now speak of as grit and resilience — is celebrated in the famous Rudyard Kipling poem that urges:

… force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: “Hold on!”

Let it go and Hold on! — in the way of so many great philosophies, those apparent opposites prove to be two sides of the same coin. To hold securely to the well-formed purposes of your will, you must let go of the vain idea that you can control people or events or the tides of fate. But you can choose what you stand for and what you will try to accomplish.

You can choose, when hopes and fears are swirling in your head, to clutch at hope. Amid beauty and ugliness, to fasten on beauty. Between despair and possibility, to pursue the possible. Of love and hate, to opt for love.

These are choices, entirely in our power to make. Charlie showed me how.

The year I met Charlie was also the year Apple introduced the first iPhone . I didn’t immediately understand the fuss. Perhaps because I write for a living, and started so long ago that I used a typewriter, I’ve always related to computers initially as fancy typing devices. The iPhone’s tiny touch screen struck me as a lousy substitute.

This was an epic example of missing the point. If I had been around when humans harnessed fire, I might have complained that the early adopters were burning up perfectly good wooden clubs.

Charlie wouldn’t have made that mistake. This was a man who understood that thriving through change begins with an eagerness for The New, even — especially — when it comes along unexpectedly.

His career is Exhibit A. Charlie’s medical education, which began in 1925, came at the threshold of modern medicine, when quacks hawking miracle potions were the norm, and genome sequencing was beyond imagination.

Charlie learned before antibiotics, when the leading causes of death in America weren’t heart disease and cancer. Today, those maladies kill mostly older people; when Charlie was a student, most people didn’t grow old. They succumbed to the same viral and microbial illnesses that had stalked humanity for ages.

Charlie didn’t cure disease in those early years — no doctors did. His stock in trade was his bedside manner, a mixture of knowledge, common sense, kindness and confidence that comforted and encouraged patients and their families while natural immunity won (or lost) its battle. Without a pill or injection to work a cure, the general practitioner was wellness coach, motivator and grief counselor in one. “All we could really do,” Charlie admitted long afterward, was “sit by our patients and pray.”

This was the case when World War II interrupted the medical practice Charlie had struggled to build through the Great Depression. Commissioned in the U.S. Army Air Corps, Capt. White was assigned to a windswept plain by the Great Salt Lake, where Camp Kearns airfield and training base took shape in a frenzy of construction. His tasks at the base hospital ranged from ambulance maintenance to the personal care of the camp commander.

The war was one of history’s most powerful engines of innovation in manufacturing, logistics, transportation, communication, computing, physical science — and medicine. Two major medical advances directly affected the midcareer doctor, turning his world upside down. In Charlie’s response lies a lesson for today: He adapted cheerfully to both of them.

The first was the mass production of penicillin , the breakthrough antibiotic medicine — an immediate blessing on humanity after which medical science would never again settle for nature’s natural course. Charlie was smart enough to recognize that penicillin spelled the death of his brand of doctoring. Physicians of the future would not be generalists making house calls. They would be specialists, masters of a narrow set of treatments or procedures. Specific expertise would rule.

The end of house-call doctoring might have demoralized Charlie, who had spent years building exactly such a practice. Instead, this curious, stoical man eagerly scanned the horizon, where he caught sight of the second major advance.

World War II, with its awful violence, transformed the use of painkillers and anesthesia. Advances in trauma surgery accelerated the use of endotracheal tubes to open airways, support breathing and administer anesthetics. Doctors perfected the use of numbing drugs administered through intravenous lines, and realized the value of local and regional blockers that could shut off pain in one part of the body without putting a patient entirely under.

These head-spinning changes came so quickly that the War Department was suddenly seeking anesthetic specialists.

Charlie reached out and seized his future.

Having earlier mentioned to his Army supervisors that he had experience administering ether, Charlie was Camp Kearns’s designated expert in anesthetics. Now, with so much urgent attention to the long-neglected field, he was promoted and given a new assignment: Report to Lincoln Army Air Field in Nebraska to serve as chief of anesthesiology at the new base hospital.

This is how Charlie found himself in 1943 in Rochester, Minn., at the Mayo Clinic, for a three-month course to turn general practitioners into anesthesiologists. The “90-day wonders,” these instant anesthesiologists were called. Charlie breezed through, then traveled to Lincoln to finish out the war.

Just like that, Charlie had turned the threat of change into an opportunity to grow. No longer was he an endangered generalist trying to hang on to a precarious piece of a dying field. Instead, when the war ended, he returned home as a pioneer in a new and rapidly growing specialty — one of the first anesthesiologists in Kansas City, and with a Mayo Clinic seal of approval.

To me, this episode contains the essence of Charlie’s life. And a crucial lesson for the rest of us.

It’s natural to feel anxiety and even fear amid looming change and intense uncertainty. My own field, journalism, has shrunk by half over the past 15 years. Artificial intelligence might finish off the other half. What will self-driving technology do to truck drivers? What will contract-writing software do to attorneys?

But it helps to understand that change is nothing new. Nearly 40 percent of Americans lived on a farm when Charlie was born. Today: 1 percent.

The fact that the future is full of uncertainty doesn’t necessarily mean it is full of gloom. Realism and optimism fit together powerfully. Too many people believe that realism — seeing the world as it is, with all its pain and threats — demands a pessimistic response. The optimist is deluded, they believe, a Pollyanna moving blindly through a bleak existence with a dumb smile.

Charlie was realistic about the professional dead end he had reached. Yet he was optimistic about new beginnings. So, when he saw a door closing up ahead, he didn’t stop and walk away. He pushed it open and strode through.

Charlie’s new life as a specialist allowed him to indulge his bottomless curiosity and zest for experiments. Horse-tank heart surgery, for instance.

After the war, one of the riskiest frontiers of medicine — and therefore among the most exciting to Charlie — was open-heart surgery. Like penicillin and anesthesia, the idea got a boost from World War II. Battlefield soldiers arrived at hospitals with shards of shrapnel in their hearts. Conventional wisdom held that the heart was inviolate; therefore, there was no way to extract these metal fragments. A heart wound was a death sentence.

But an Iowa-born doctor named Dwight Harken , billeted to a London military hospital, reasoned that if soldiers were going to die anyway, there was no harm in trying to save them. He experimented with finger-size incisions in the heart wall to allow him to reach quickly inside and remove the shrapnel. The gamble was a huge success: Harken saved more than 125 lives.

After the war, Harken and others realized that the same technique might be useful in treating mitral valve stenosis , a potentially fatal condition that often resulted when a youthful strep throat infection worsened into rheumatic fever. Fibrous tissue inside the heart caused the mitral valve to narrow, leading to high blood pressure, blood clots, blood in the lungs and even heart failure.

Charlie and his colleagues in Kansas City were intrigued to read in medical journals about experimental surgery to repair stenotic valves. “The surgeon could reach in real quick,” Charlie said, and with his finger probe for the fibrous tissue, stretch the valve, break the adhesion and get out. “The whole thing could be done in under an hour.”

But even a relatively brief valve surgery ran a high risk of death unless the flow of blood through the heart could be slowed dramatically. Researching the matter further, Charlie learned of experiments in which patients under anesthesia were chilled to thicken and slow the flow of blood. To pioneer open-heart surgery in Kansas City, he simply needed to figure out how to safely chill an unconscious patient.

Enter the horse tank.

After work one day, Charlie was tending to some horses he had purchased along with a little plot of land. As he worked, his eye fell on the large oval trough that held water for his livestock. In a flash, he realized this was just what he needed.

A horse tank was big enough to hold a sleeping patient. “I bought a horse tank and we put the patient under anesthesia and packed him in ice,” Charlie told me. When he was cold enough, “we lifted him from the tank full of ice, placed him on the operating table, and quickly the surgeon opened the chest and made an incision in the heart. He went inside, broke up the fibrous tissue, sewed him back up, and it was done. In an hour, the patient was all thawed out.”

Charlie’s horse tank served as the leading edge of cardiac surgery in Kansas City for some time. “We never lost a patient,” he said.

People familiar with the lingo of Silicon Valley might recognize in this story what is known as IID — iterative and incremental development. It is a supremely practical, pragmatic approach to change, a philosophy that recognizes that great transformations rarely come as single thunderbolts.

There is a Stoic flavor to the approach, because it works with the material and the moment at hand, rather than pine after something better beyond one’s grasp. IID says: Don’t demand a perfect solution before tackling a problem. Move step by step (that’s the incremental part), improving with each new learning experience (that’s the iterative part).

Thomas Edison tested 6,000 filaments to find the best one for his lightbulb. Charlie understood that open-heart surgery wouldn’t arrive in fully formed glory, like a Hollywood ending. First, progress had to spend a year or two in an ice bath rigged from farm equipment.

This is how we live with change: step by step. This is how even elderly and change-resistant people have learned to pump their gasoline with a credit card reader and watch their great-grandchildren take first steps on social media. Charlie embraced that he would be learning new things as long as he lived, and he moved forward by accepting that he would advance in small increments.

He was also willing to make mistakes. Charlie told me he was glad to have worked in an era before malpractice lawsuits were common — when he could participate in what he estimated to be about 40,000 surgeries and “be innovative and not fear the stab of the lawyers, you know?”

And mistakes didn’t come only in the operating theater. After the war, when a buddy suggested that Charlie invest in a fledgling Colorado ski resort called Aspen , he scoffed: “That’s just a ghost town!”

Definitely a mistake.

A salesman by the name of Ewing Kauffman once tried to interest Charlie in a start-up business he had launched in his basement. “He was cleaning oyster shells in a washing machine and grinding them into antacid powder,” Charlie said, still slightly incredulous. Charlie held on to his money. Kauffman’s business, Marion Labs , became a major pharmaceutical company worth billions.

Another mistake.

I once commented on the various fortunes Charlie had missed, and he cheerfully replied that I didn’t know the half of it. He seemed to derive as much delight from recalling these blunders as he did from remembering his triumphs.

Mistakes can have virtue, Charlie knew. They show we’re making the effort, engaging with life, “ in the arena ,” as Theodore Roosevelt put it. Or as Epictetus, that marvelous Stoic, said: “If you want to improve, be content to be thought foolish and stupid.”

Avery long life is like a very large mansion. There are many rooms and all the rooms are big. Charlie had not one but two careers as a doctor: years as a general practitioner, followed by decades as an anesthesiologist. His retirement was as long as most careers. He had not one but two long marriages, plus years as a single man.

Everywhere he went, of course, people asked him for his secret to longevity. His answer was deflating: just luck, he insisted.

His genome, over which he had no influence, had not betrayed him with a weak heart or a wasting disease. Unlike his father, Charlie never saw his number come up in the cosmic lottery of freak accidents.

Luck.

His mother started a May morning in 1914 as the married parent of five children and by noon was a widow with no job and no prospects. She didn’t go to pieces. She turned her home into a boardinghouse and encouraged her children to pitch in. She taught them to be independent and self-sustaining simply by “putting the responsibility of life on us,” as Charlie remembered fondly. Because she believed in them, they believed in themselves.

Luck.

Charlie was also, of course, fortunate to have been a White man in the 20th-century United States, free to go where he pleased and dream as big as he wanted. The same Midwest of the 1920s that nurtured his optimistic spirit was a hotbed of populist nationalism and the Ku Klux Klan. Unlike women and people of color, he could seize opportunities because doors were open to him that were closed to so many others.

Luck.

Charlie’s stepdaughter began feeling poorly after a vacation at age 66. A scan disclosed tumors throughout her body and she was gone within months. A few weeks after she died, Charlie turned 102.

Luck.

That’s the age Charlie was when I met him.

My luck.

In 2012, when he was 106, Charlie slipped on a patch of ice outside his front door one frigid day, and his ankle broke with a pop. In typical fashion, he shrugged it off.

At 107, he was hospitalized with pneumonia — a disease so efficient at bringing long lives to relatively merciful ends that it has a nickname: the old man’s friend.

Nope.

Then, at 108, Charlie at last lost his independence. He moved into a nursing home, and one day word came from his family that he was fading fast, telling loved ones that death was near and assuring them he was ready. His wide circle of friends and admirers braced for fate to catch at his collar. But springtime blossomed again, and Charlie had a change of heart. His birthday was near, and having come so far, he decided he might as well keep going to 109.

How unlike Charlie, I thought to myself — to imagine he had control over something as powerful and capricious as death. One of the core teachings of Stoicism is that death keeps its own datebook; it can come at any time, and the only certainty is that it will eventually get to you. Therefore, “ let us postpone nothing ,” said the amiable Roman philosopher and playwright Seneca. “Let us balance life’s books every day.”

The glories of May warmed into June, sweltered into July. On the day my phone finally rang — Charlie was gone — I checked a calendar, then shook my head, which swam lightly in a flood of amazement and delight. It was Aug. 17, 2014. Quietly, in the wee hours after his birthday, Charlie had let go.

In the end, Charlie defied the actuaries to become one of the last men standing — one of only five fellows from the original 100,000 expected to make it to 109. By the time he was done, he had lived nearly half the history of the United States.

Among Charlie’s things after he was gone, his family found a single sheet of notepaper, on which Charlie had boiled 109 years into an operating code of life. He filled the sheet front and back in flowing ballpoint pen, writing in definitive commands. Among them:

Think freely. Practice patience. Smile often. Forgive and seek forgiveness.

Feel deeply. Tell loved ones how you feel.

Be soft sometimes. Cry when you need to. Observe miracles.

As I studied Charlie’s list, it seemed to me that each directive, by itself, was like a greeting card or a meme. Charlie’s takeaways from more than a century of living were things we already know, for we have heard them a thousand times.

But after a few years to think about it, I have arrived at a theory that a life well-led consists of two parts.

In the first, we are complexifiers. We take the simple world of childhood and discover its complications. We say, “yes — but …” and “maybe it’s not that easy.” Nothing is quite as it seems.

Then, if we live long enough, we might soften into the second stage and become simplifiers. For all the books on all the shelves of all the world’s libraries, life must in the end be lived as a series of discrete moments and individual decisions. What we face might be complicated, but what we do about it is simple.

“Do the right thing,” Charlie remembered his mother telling him.

“Do unto others,” a teacher told his disciples, “as you would have them do unto you.”

Charlie lived so long that the veil of complexity fell away and he saw that life is not so hard as we tend to make it. Or rather: No matter how hard life might be, the way we ought to live becomes a distillate of a few words. The essentials are familiar not because they are trite, but because they are true.

Yes it's a long article but hey, Charlie lived a long life worthy of it.

Not simply a long article, but an article with substance just like Charlie.

RIP Charlie