Mississippi Is Offering Lessons for America on Education

JACKSON, Miss. — The refrain across much of the Deep South for decades was “Thank God for Mississippi!” That’s because however abysmally Arkansas or Alabama might perform in national comparisons, they could still bet that they wouldn’t be the worst in America. That spot was often reserved for Mississippi.

So it’s extraordinary to travel across this state today and find something dazzling: It is lifting education outcomes and soaring in the national rankings. With an all-out effort over the past decade to get all children to read by the end of third grade and by extensive reliance on research and metrics, Mississippi has shown that it is possible to raise standards even in a state ranked dead last in the country in child poverty and hunger and second highest in teen births.

In the National Assessment of Educational Progress, a series of nationwide tests better known as NAEP, Mississippi has moved from near the bottom to the middle for most of the exams — and near the top when adjusted for demographics . Among just children in poverty, Mississippi fourth graders now are tied for best performers in the nation in NAEP reading tests and rank second in math.

The state has also lifted high school graduation rates. In 2011, 75 percent of students graduated , four percentage points below the national average; by 2020, the state had surpassed the national average of 87 percent by one point.

“Mississippi is a huge success story and very exciting,” David Deming, a Harvard economist and education expert, told me. What’s so significant, he said, is that while Mississippi hasn’t overcome poverty or racism, it still manages to get kids to read and excel.

“You cannot use poverty as an excuse. That’s the most important lesson,” Deming added. “It’s so important, I want to shout it from the mountaintop.” What Mississippi teaches, he said, is that “we shouldn’t be giving up on children.”

The revolution here in Mississippi is incomplete, and race gaps persist, but it’s thrilling to see the excitement and pride bubbling in the halls of de facto segregated Black schools in some of the nation’s poorest communities.

One of the reasons I became interested in writing this series about how we can help those whom America has left behind was the loss of an old school friend when she froze to death while homeless. Since then, I’ve lost too many friends I grew up with to drugs, alcohol and suicide, and as I think about what might have saved their lives, education is high on the list.

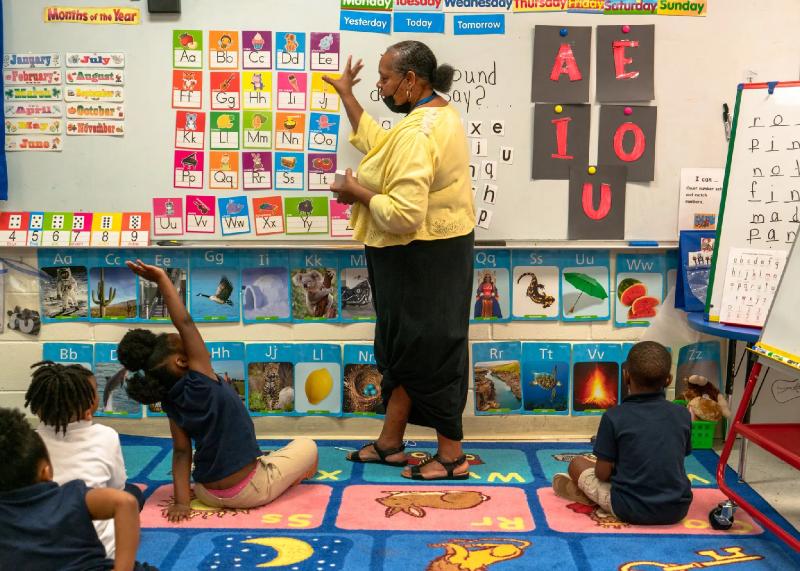

But an education system can save people only when it manages to educate them, and America too often falls short. I had heard Mississippi cited for its progress, but frankly, I was skeptical until I visited. On my second day in Jackson, where 98 percent of public school students are people of color, mostly from low-income families, I visited a second-grade classroom.

The class was reading a book, “The Vegetables We Eat.” The children read aloud and debated what vegetables were. Things that are green? Foods that don’t taste good? I was startled to see second graders read words like “vegetables” and “eggplant” fluently and still more astonished to see the entire class easily read the sentence “Where does nourishing food come from?”

Mississippi has achieved its gains despite ranking 46th in spending per pupil in grades K-12. Its low price tag is one reason Mississippi’s strategy might be replicable in other states. Another is that while education reforms around the country have often been ferociously contentious and involved battles with teachers’ unions, this education revolution in Mississippi unfolded with support from teachers and their union.

“This is something I’m proud of,” said Erica Jones, a second-grade teacher who is the president of the Mississippi affiliate of the National Education Association, the teachers’ union. “We definitely have something to teach the rest of the country.”

***

Mississippi’s success has no single origin moment, but one turning point was arguably when Jim Barksdale decided to retire in the state. A former C.E.O. of Netscape, he had grown up in Mississippi but was humiliated by its history of racism and underperformance.

Barksdale cast about for ways to improve education in the state, and in 2000 he and his wife contributed $100 million to create a reading institute in Jackson that has proved very influential. Beyond the money, he brought to the table a good relationship with officials such as the governor, as well as an executive’s focus on measurement and bang for the buck — and these have characterized Mississippi’s push ever since.

With the support of Barksdale and many others, a crucial milestone came in 2013 when state Republicans pushed through a package of legislation focused on education and when Mississippi recruited a new state superintendent of education, Carey Wright, from the Washington, D.C., school system. Wright ran the school system brilliantly until her retirement last year, meticulously ensuring that all schools actually carried out new policies and improved outcomes.

One pillar of Mississippi’s new strategy was increasing reliance on phonics and a broader approach to literacy called the science of reading , which has been gaining ground around the country; Mississippi was at the forefront of this movement. Wright buttressed the curriculum with a major push for professional development, with the state dispatching coaches to work with teachers, especially at schools that lagged.

The 2013 legislative package also invested in pre-K programs, targeting low-income areas. Mississippi made the calculated decision to offer high-quality full-day programs, with qualified teachers paid at the same rate as elementary school staff members, rather than offer a second-rate program to more children.

Most of the class was sitting on the floor and enthusiastically answering the teacher’s questions. Meanwhile, Allyson was running around the classroom, trying to see if she could run faster than her shadow.

“Every classroom has an Allyson,” another teacher said with a sigh. All the early-grade teachers I spoke to said that the Allysons of Mississippi are less disruptive and more ready to learn after attending pre-K.

Perhaps the most important single element of the 2013 legislative package was a test informally called the third-grade gate: Any child who does not pass a reading test at the end of third grade is held back and has to redo the year.

This was controversial. Would this mean holding back a disproportionate share of Black and brown children from low-income families, leaving them demoralized and stigmatized? What about children with learning disabilities?

In classrooms, I saw charts on the wall showing how each child — identified by a number rather than a name — ranks in reading words per minute. Another line showed which children, also noted by number, were green (on track to pass) and which were yellow (in jeopardy). Then there were some numbers representing children who were red and urgently needed additional tutoring and practice.

As third grade progresses in Mississippi, there is an all-consuming focus on ensuring that every child can read well enough to make it through the third-grade gate. School walls fill with posters offering encouragement from teachers, parents and students alike.

“Blow this test out of the water,” wrote Torranecia, a fifth grader, in a typical comment.

In the town of Leland in the Mississippi Delta, one of the poorest parts of America, parents and family members come early on the day of the big exam and line a hallway at the elementary school, cheering madly as the kids walk through to take the test — like champion football players taking the field. And when I visited, 35 new bicycles were on display in the school gym, donated by the community to be awarded by lottery to those who passed.

Those who did not pass would get a second chance at the end of the school year. Children who fail this second try are urged to enroll in summer school as a last desperate effort to raise reading levels. Those who fail a third time are held back — about 9 percent of third graders — although there is a chance for a good-cause exemption if, for example, a child has a learning disability or speaks limited English.

What happens to the children forced to repeat third grade? A Boston University study this year found that those held back did not have any negative outcomes such as increased absences or placement in special education programs. On the contrary, they did much better several years later in sixth-grade English tests compared with those who just missed being held back. Gains from being held back were particularly large for Black and Hispanic students.

With such a focus on learning to read, one of the surprises has been that Mississippi fourth graders have also improved significantly in math. One possible explanation is that some math problems require reading; another is that children try harder in all subjects when they enjoy school.

The state and the Barksdale Reading Institute also partnered in experimenting with approaches that failed; in those cases, they measured the results and dropped methods that didn’t show gains. They tried to lure family members into visiting schools through drop-in centers, and few showed up. They tried to introduce approaches through teacher training in universities, and this proved expensive and much less successful than dispatching coaches to offer guidance in the classrooms.

Mississippi is also striking for what it didn’t do. For example, it didn’t reduce class sizes: Officials weighed the evidence and concluded that while smaller classes would improve outcomes, spending the money on teacher coaching and student tutoring would help even more.

Nothing worked quite as expected, and everything was harder than it looked. But Mississippi kept testing and tweaking its model, following the evidence where it led. And now second graders can read “nourishing.”

***

Many white families fled the Mississippi public school system around the time courts forced integration in 1970, so 48 percent of public school students were Black in 2018-19 and 44 percent white — with three-quarters of all pupils labeled economically disadvantaged.

One challenge is that while Mississippi has made enormous gains in early grades, the improvement has been more modest in eighth-grade NAEP scores. Still, the state has made progress in several areas that help upper grades: getting parents more involved and promoting vocational education, in addition to raising high school graduation rates.

The school superintendent in the town of Hollandale, Mario Willis, told me his high school graduation rate was 97 percent , and he explained how his school fights to keep kids. The other day, he said, he had a call from the high school principal about an 18-year-old senior who was dropping out.

The student lived in poverty and had a single mom who was unemployed, so the family’s economic situation was desperate. Not seeing a way out, the young woman left school and took a restaurant job.

That’s when the school went all out to bring the student back. School officials repeatedly visited the young woman at home. They spoke to her mother, and they talked her employer into arranging work hours for her after school.

So now she is back in school, on track to graduate.

***

Other states, particularly Alabama, have adopted elements of Mississippi’s approach and have improved outcomes — but not nearly as much as Mississippi has. Perhaps that’s because those states’ leaders didn’t work as hard or because Alabama until recently didn’t have a must-pass third-grade reading test, but it’s also true that Mississippi has been guided by a visionary leadership team that may be difficult to recreate elsewhere.

All of these education leaders, along with Superintendent Wright, reinforced one another and brought in others with fresh ideas who were utterly committed to lifting Mississippi standards — and as state test results improved, politicians responded with pride and allocated more funds to the cause. Last year, Mississippi passed a major increase in teacher pay.

Since so much of the debate about K-12 education is about teachers’ unions and whether they prevent improvement, let me make the point that the states with arguably the best public schools (such as Massachusetts and New Jersey) have strong teachers’ unions while the state with some of the most-improved schools (Mississippi) has weak teachers’ unions. We needn’t get bogged down by debates over unions.

The education reform movement that for decades captured the imagination of tech executives, documentary makers and presidents from Ronald Reagan to Barack Obama and Donald Trump has fizzled . We no longer hear presidents and opinion makers regularly describe education as the civil rights issue of our time. Many people seem to have given up and moved on.

Mississippi is one answer to that sense of exhaustion and futility. And other states are noticing. Education Week reported that 31 states have passed legislation on evidence-based reading instruction. Many school systems, most recently New York City ’s, are adopting the science of reading, based partly on the success in Mississippi and elsewhere.

Education reformers have often thought it hopeless to tackle state public school systems directly and so have pursued the equivalent of bank shots: Run effective charter schools, for example, and public schools can adopt lessons learned. Mississippi raises the question of whether we truly need bank shots. Or maybe for the United States, the whole state of Mississippi is the ultimate bank shot.

The Barksdale Reading Institute is developing a free online tool, Reading Universe , to make the state’s approach to reading available to all schools in America and around the world. The idea is that kids everywhere should have the same opportunities to learn and graduate as, say, students in high-poverty schools in the Delta.

Thank God for Mississippi.

This is a good thing! No Debbie Dumber Doomers please, there are ample seeds for that.

First up, how to spell the state you live in.

Of course all the kids giggle when they get to pp.

An encouraging sign for Mississippi.