The Treason Of Robert E Lee

excerpted from

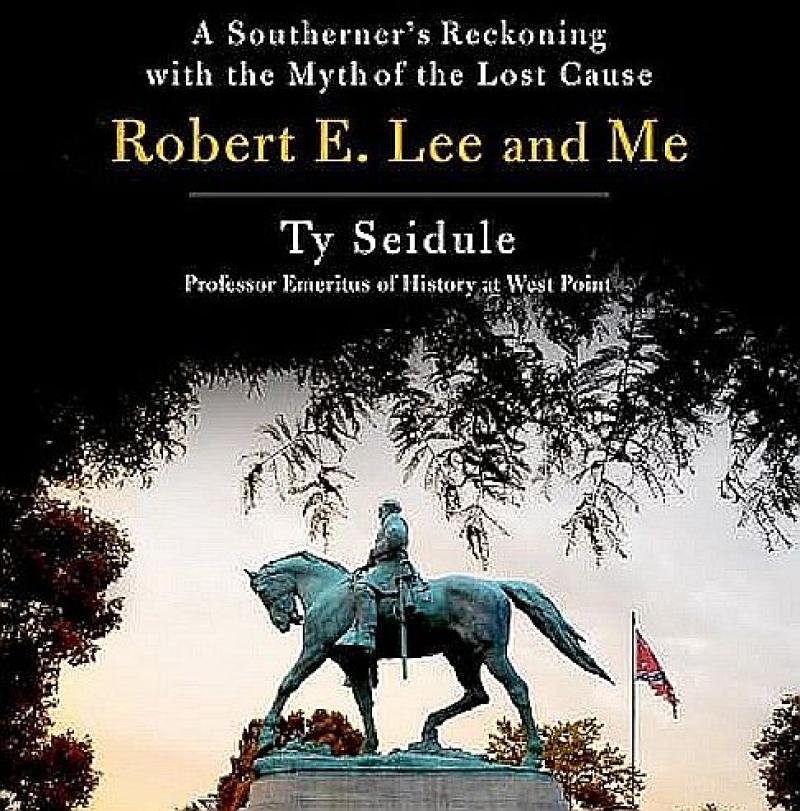

Robert E. Lee and Me

by Ty Seidule

.....When I read Article III, Section 3, I thought immediately of Lee: Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort. No Person shall be convicted of Treason unless on the Testimony of two Witnesses to the same overt Act, or on Confession in open Court.

Robert E. Lee served in the U.S. Army either as a cadet or as a Regular Army officer from 1825 to 1861. Thirty- six years. Yet at the age of fifty-four, he committed treason. No court ever convicted him, although he was indicted. Lee was paroled at Appomattox and eventually granted full amnesty, as all former Confederates were on Christmas Day 1868. I am not arguing that a jury found him guilty; none did. But I don’t need a conviction to analyze facts. When I read Article III, Section 3, Lee’s actions undeniably violated the Constitution he and I swore to defend. He waged war against the United States. Because he fought so well for so long, hundreds of thousands of soldiers died. No other enemy officer in American history was responsible for the deaths of more U.S. Army soldiers than Robert E. Lee. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia killed more than one in three and wounded more than half of all U.S. casualties. In the last year of the war, Lee’s army killed or wounded 127,000 U.S. Army soldiers.

Lee killed American soldiers; that’s a fact. But is it fair for me as a U.S. Army officer or a historian to pronounce judgment? Can I question Lee’s decision to fight against the country that educated him? The country that he served for so long and so well? He lived in the nineteenth century, I live in the twenty-first, but we both wore army blue for more than thirty years. His decision to resign his U.S. Army commission and fight against the United States haunts me because of my background as a southerner and because of my own army service. As a soldier and as a historian, I need to see beyond the myth I grew up believing to understand the man and his decision. Until recently, historians used Lee’s Pulitzer Prize winning biographer Douglas Southall Freeman’s take on the issue from 1935. Freeman wrote that leaving the United States to fight for the Confederacy was “the answer he was born to make.”

In his superb Pulitzer Prize–winning book, Battle Cry of Freedom, published in 1988, James McPherson called Lee’s decision “foreordained by birth and blood.” Emory Thomas, who wrote a well- received biography in 1995, wrote that if Lee had stayed with the U.S. Army, he “would have elected infamy.” As recently as 2005, a Pulitzer Prize–nominated historian of the South, Bertram Wyatt-Brown, wrote that “Lee had no choice in the matter” and that choosing the United States would be “the coward’s way out.” I disagree. Lee’s decision was not fated.

Recent historians have made a compelling case that Lee could have chosen differently. I will go further than that. Lee should have chosen differently because almost every part of his life up to 1861 pointed toward fighting for the United States, starting with his education. In 1829, Lee graduated from West Point, the most national institution in the country. An officer who graduated in 1841 wrote that the Military Academy “taught that he belongs no longer to section or party but, in his life and all his faculties, to his country.” Another West Point graduate wrote that the academy taught all cadets the “doctrine of perpetual nationality.” One aspect of that “perpetual nationality” took the form of an oath West Point cadets signed when they began as a cadet and took at commissioning and every time an officer received a promotion. For me the oath is the essence of why I serve.

Lee signed an oath at every promotion. In 1855, while at West Point as superintendent, Lee signed this oath: I, Robert Edward Lee, appointed a Lieutenant Colonel of the Second Regt. of Cavalry in the Army of the Unit- ed States, do solemnly swear, or affirm, that I will bear true allegiance to the United States of America, and that I will serve them honestly and faithfully against all their enemies or opposers whatsoever; and observe and obey the orders of the President of the United States, and the orders of the officers appointed over me, according to the Rules and Articles for the Government of the armies of the United States. Lee took his next promotion to colonel on March 30, 1861, after Lincoln selected him for a coveted assignment as commander of the 1st U.S. Cavalry Regiment, a storied unit that is still on active duty today. One reason Lee received the promotion was the belief that he would remain with the United States. When Secretary of War Simon Cameron asked General Winfield Scott if he retained confidence in Colonel Lee’s loyalty to the flag in 1861, Scott replied, “Entire confidence, sir. He is true as steel, sir, true as steel!” Lee did not hesitate to accept command and with it a colonelcy. Colonel was an exalted rank in the Regular Army before the Civil War. In fact, the first West Point graduate made brigadier general only in 1860.

After Lee accepted the promotion, events quickly led to war. Lincoln reinforced the garrison at Fort Sumter rather than surrender federal property to South Carolina. On April 12, Pierre G. T. Beauregard and the Confed- erate forces attacked the U.S. garrison at Fort Sumter, South Carolina. On the fifteenth, President Lincoln called for seventy-five thousand volunteer soldiers to quell the rebellion. In reaction, white Virginians at their Secession Convention voted to secede if the state’s white men approved a referendum on May 23. Lee did not wait for the referendum, perhaps because he worried that war would commence before that date. Or because he hoped for high rank in the new army. Army officers then and now are an ambitious lot. After wearing the eagles of a U.S. Army colonel for less than three weeks, on April 20, 1861, Lee mailed his resignation letter to the War Department. On the twenty-second, he accepted a commission from Virginia as a major general. When he pledged to fight against the United States, he was still in the U.S. Army; his resignation was accepted on the twenty-fifth, three days later. Lee couldn’t even wait until his resignation processed—three days—before he took a train to Richmond to accept a wartime commission from a rebellious state. How could Lee take a promotion and the oath and then resign three weeks later? Southern leaders did approach him in mid-March, but historians are divided on whether he had accepted an offer before his resignation. The thirty-six hours between resignation and acceptance of a commission from Virginia gives pause, but there is no hard evidence.

Before he left the U.S. Army, Lee’s letters to family and friends indicated he believed in the United States no matter what. One letter talked about Lee’s understanding that the United States was a “perpetual union,” the same words found in the Articles of Confederation. Lee saw “disunion as evil” and believed “secession is nothing but revolution” and “anarchy.” Another letter was even more clear, writing that his country “was the whole country. That its limits contained no North, no South, No East no west, but embraced the broad Union, in all its might & strength, present & future. On that subject my resolution is taken, & my mind fixed.” Ending his missive emphatically, he underlined the next sentence: “I know no other Country, no other Government, than the United States & their Constitution.” Wow. I like that declaration. Yet we know he quit the United States only a few years later. While he said, “Union always,” he later allowed that if there was no other option and Virginia seceded, he would follow. In Richmond, just after tendering his resignation, he told the Virginia House of Delegates, “I devote myself to the service of my native State, in whose behalf alone will I ever again draw my sword.”

Growing up in Virginia, I thought Lee went with the Confederacy because all of his family, friends, and army colleagues pushed him in that direction. Wrong. Much of his extended family wanted to stay in the Union. Not just in 1861, but for generations past. In 1794, his father, “Light-Horse” Harry Lee, the great Revolutionary War general, joined George Washington and thirteen thousand U.S. soldiers to put down the first rebellion since the Constitution was signed, the Whiskey Rebellion in western Pennsylvania. While Harry Lee had once called Virginia his “country,” he later decided that “our happiness depends entirely on maintaining our union” and that “in point of right, no state can withdraw itself from the union.”

Robert E. Lee chose to wage war against the United States despite the unionist beliefs of much of his extended family, many of whom remained loyal throughout the Civil War. His cousin Samuel Phillips Lee served honorably in the U.S. Navy. John Fitzgerald Lee (Samuel’s brother) went to West Point and served as judge advocate of the U.S. Army. His cousin Lawrence Williams stayed loyal and had two sons in the U.S. Army. Lee’s first cousin Edmund Jennings refused to let any friend or foe talk secession in his presence. Charles B. Calvert, a cousin on both sides of the Lee family, was a slaveholding unionist who supported Lincoln and served as a congressman from Maryland. Two of Lee’s closest friends, Edward Turner and Cassius Lee, remained loyal to the United States. Even Lee’s sister Anne Lee Marshall maintained her stand with the United States, and her son Louis fought in blue. In fact, neither Anne nor anyone else in that family ever talked to Lee again.

About twenty years ago, Lee’s best biographer, Elizabeth Brown Pryor, found a letter from Lee’s daughter Mary that shed new light on her father’s decision to fight against the United States. Lee’s decision “bewildered” his immediate family, who thought he would stay with the Union. Lee’s daughter wrote, “We were traditionally, my mother especially, a conservative or ‘Union’ family.” Mary Lee wrote that Lee did not rush to tell his family about his decision to resign, perhaps because he was embarrassed. When he finally gathered them in his office, he told them, “I suppose you all think I have done wrong.” Like the majority of his friends and extended family, Lee’s nuclear family mainly opposed Virginia’s “ordinance of revolution.” Lee’s wife maintained her staunch unionist views into 1861. Eventually, she became an ardent Confederate, but not until after her precious Arlington home was occupied by the U.S. Army. Lee’s son Custis, a popular officer at West Point in 1861, was initially “no believer in secession,” as a cousin remembered. Rooney, Lee’s second son, reacted glumly to the excessive celebration after secession was announced. “He said people had lost their sense and had no conception of what a terrible mistake they were making.” Both Fitz and Rooney would later become Confederate generals, but they delayed their decision on secession until weeks after their father.

If Lee’s family and friends leaned Union, so too did his army contemporaries. Lee’s mentor and hero was General Winfield Scott, a Virginian. Scott was the greatest American soldier from the War of 1812 to the beginning of the Civil War. He joined the army in 1808, and by 1814 he had been promoted to brigadier general. He would continue to serve as a general for the next forty-seven years, to include twenty years as the commanding general of the army. Scott, the Virginian, never once considered leaving the army for his home state. When a Virginia delegation approached Scott about service in the commonwealth, he rejected the notion immediately. Scott emphasized in February 1861 that “it is my duty to suppress insurrection—my duty!”

Scott was hardly the only southerner to remain loyal. The Virginian George Thomas is now one of my heroes for staying loyal and fighting the rebellion with courage and skill. He saved the U.S. Army from destruction at the Battle of Chickamauga in 1863, earning the nickname the Rock of Chickamauga. In the winter of 1864, Thomas destroyed John Bell Hood’s Confederate Army of Tennessee at the Battle of Nashville. Thomas later told a colleague, Thomas B. Van Horne, that “there is no excuse whatever in a United States officer claiming the right of secession.” Van Horne reported that Thomas “believed that there was a moral and legal obligation which forbade resignation, with a view to take up arms against the Government.” By the end of the war, Thomas harshly condemned the entire Confederacy: “Their cause was cursed in the beginning, but their infatuation has led them on a suicidal course until they now see nothing before them but disgrace and infamy.” I couldn’t agree more.

Plenty of other Virginians and other southerners felt and acted like Thomas. The Virginian Philip St. George Cooke graduated from West Point two years before Lee but never wavered in his loyalty, famously declaring, “I owe my country much, my state little.” Cooke’s family provided him with many reasons to leave the Union. His son-in-law was J. E. B. Stuart, Lee’s cavalry commander. Stuart, the Confederate, was so angry at his father-in-law’s choice that he renamed his son from Philip St. George Cooke Stuart to James Ewell Brown Stuart Jr. Both of Cooke’s sons also fought for the Confederacy. Yet it’s Cooke’s stirring words that reflect the true West Point graduate and U.S. Army officer: The National Government adopted me as a pupil and future defender; it gave me an education and a profes- sion, and I then made a solemn oath to bear true allegiance to the United States of America, and to “serve them honestly and faithfully against all their opposers whatsoever.” This oath and honor forbid me to aban- don their standard at the first hour of danger.

By May 1861, eight West Point graduates from Virginia had a colonelcy in the U.S. Army. It took an average of thirty years for those eight to reach colonel after graduating from the U.S. Military Academy. The Virginian René De Russy, class of 1812, waited forty-six years to pin on that rank. Looking carefully at those eight U.S. Army colonels from Virginia confirms that Lee’s decision was abnormal. Of those eight, seven remained loyal to their solemn oath to the U.S. Constitution. Only one colonel resigned to fight against the United States. Robert E. Lee. Put another way, 88 percent of long-serving Regular Army colonels from Virginia stayed with the United States. If we expand the scope to include all slave state U.S. Army colonels who graduated from West Point the total number jumps to fifteen. Of those fifteen, twelve remained loyal, or 80 percent. Lee was an outlier. Most officers of his experience and rank remained with the United States.

Growing up in Virginia, I saw no monument to these brave and loyal men. I still don’t. The more I learned about Lee’s decision, the more I realized that he did not have to leave the U.S. Army. Freeman’s admonition that joining the Confederacy was “the answer he was born to make” is another lie from the Lost Cause myth. Lee chose to renounce his oath. I’m not making a presentist argument in thinking Lee’s decision was wrong. Plenty of other senior southern army officers agreed with the Constitution’s definition of treason, agreed that Lee dishonored thirty years of service. When a senior officer, a colonel, is asked to fight for his country, he or she fights unless given an unlawful order. Fighting a rebellion was and remains a lawful order. In fact, one of the reasons for the creation of the U.S. Constitution was the inability to suppress rebellions, like Shays’s Rebellion in Massachusetts. The U.S. Army has crushed rebellions throughout its long history. Disagreement with policy is no excuse to take up arms against the government. Other Regular Army officers fought in Mexico, even though they felt the war unjust. Officers fought against Native Americans when that cause was unpopular and seen by some as morally unac- ceptable and even reprehensible. The military doesn’t practice democracy; the military enforces democracy. In 1861, Lincoln was elected fairly under the U.S. Constitution. U.S. Army officers who chose war against the president of the United States and the Constitution were in rebellion and, by law, traitors.

As a professional soldier, Lee resigned, but could he ever go against the oath’s prescription to defend “the United States, paramount to any and all allegiance … to any State,” or “against all enemies or opposer”? In my opinion, no. Not legally or ethically. And of course, fighting for slavery meant it was morally wrong too. One cousin, after hearing of Lee’s decision made after praying for guidance, coldly replied, “I wish he had read over his commission as well as his prayers.” Another West Point graduate, Henry Coppée, criticized Lee in print in 1864. “Treason is Treason,” he said. Lee “flung away his loyalty for no better reason than a mistaken interpretation of noblesse oblige.”

Lee could have chosen differently. Like Scott and Thomas, he could have fought for the United States. Or he could have sat out the war. Lee was fifty-four and older than most of the battlefield commanders. Alfred Morde- cai, West Point class of 1823, was the leading expert on ordnance in the country. A North Carolinian by birth, Mordecai rejected an offer to serve in the Confederacy but still resigned his U.S. Army commission and sat out the war teaching mathematics in Philadelphia. Nor did Lee try to use his influence to stop Virginia from seceding. The consequences of Lee’s betrayal led many others on the path to treason. Lee’s decision was momentous because of his status: son of an American Revolution war hero, Mexican-American War hero, army colonel, son- in-law of George Washington’s adopted son, and suppressor of John Brown’s raid. In Alexandria, all looked to Lee. The local newspaper, my hometown paper, the Alexandria Gazette, wrote on the day Lee mailed his resignation, but before his decision was announced, “We do not know, and have no right to speak for or anticipate, the course of Col. Robert E. Lee. Whatever he may do, will be conscientious and honorable.” The pro-secession Gazette put no pressure on Lee to resign. If he did resign, the paper hoped Virginia would give him command of its troops. The paper fawned over him. “His reputation, his acknowledged ability, his chivalric character, his probity, honor and—may we add, to his eternal praise—his Christian life and conduct—make his name a ‘tower of strength.’” Lee’s actions carried great weight in Virginia and among army officers. One person who lived near Arlington noticed that “none of them wanted secession, and were waiting to see what Colonel Robert Lee would do.”

A relative noted, “For some the question ‘What will Colonel Lee do?’ was only second in interest to ‘What will Virginia do?’” Lieutenant Orton Williams, Mary Lee’s cousin, was aide-de-camp to Winfield Scott. When Williams heard the news, he said, “Now that ‘Cousin Robert’ had resigned everyone seemed to be doing so.” Would as many officers have resigned their commission if the popular Robert E. Lee had remained loyal? Of course, we will never know, but Lee’s decision was momentous not only for his family but for many others trying to decide what to do.⁵²

THIS IS AN ARTICLE IN THE HISTORY SECTION OF NEWSTALKERS, IF IT OFFENDS YOU DONT COMMENT.

OFF TOPIC COMMENTS WILL BE REMOVED.

Article is LOCKED by author/seeder

Article is LOCKED by author/seeder

Guess FDR disagreed with you, orf maybe it was just part of his Southern Strategy:

FDR was not a historian at West Point, as Ty Seidule was.

James Tyrus Seidule (born 1962) is a retired United States Army brigadier general, the former head of the history department at the United States Military Academy, the first professor emeritus of history at West Point, and the inaugural Joshua Chamberlain Fellow at Hamilton College.

Exactly, FDR knew politics more than history.

It seems that with Lee there are many contradictions perhaps they will never be understood. I always thought that his wish not to have any monuments dedicated to him was contradictory, but that was Lee.

When Lee surrendered his army to U.S. Grant at Appomattox Grant's long-time friend, a fellow officer, and Native American Lt. Col Ely S. Parker a Seneca leader from the Tonawanda Reservation in NY. General Lee would not shake hands with Parker thinking that his dark skin he was black, after recognizing Parker as a Native American, extended his hand and said, ''I am glad to see one real American here.''.

A most controversial person.

He was present at the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia where he helped draft the surrender documents and render them in his own hand. At the time of the surrender, General Robert E. Lee is said to have mistaken Parker for a black man, but apologized saying, "I am glad to see one real American here," to which Parker responded, "We are all Americans, sir."

Very wise man.

Nature or nurture?

History can have some surprising complexity. Today, those who hail from Appalachia are typically hailed a hick rednecks.

Truth is that during the Civil War they either supported the North or were ambivalent about it.

Unionists sentiment was strong in what is now W VA and the wanted secession (the good kind) from VA.

The same in East Tenn. Although Tennessee provided a large number of troops for the Confederacy, it would also provide more soldiers for the Union Army than any other state within the Confederacy.The

Then there is AL. As Federal troops made their way into the region, Union officers recognized the potent patriotism of the Alabama Unionists. Formed in 1862, the First Alabama Cavalry went on raids to sabotage Confederate communications, marched with Gen. William T. Sherman’s forces across the South, and contributed to the fall of Vicksburg and the destruction of Atlanta.

I don't think that the 1619 Project captured this history.

People then were like people now, binary, right or wrong, ignorant or knowledgeable. Nuance is a myth. Today's presentism is the only lens to view our past.

It's interesting how much angrier are modern liberals are about reconciliation with the South than the people who actually fought Lee and lost friends and loved ones in the War.

They didn't have a problem with monuments to fallen Confederate soldiers. Grant had southern general carry his coffin during his funeral procession. But the modern progressive is more zealous to destroy a monument to Confederates than puritans were to destroy the images of saints.

Maybe if people stopped defending Robert E Lee, and complaining when statues to a traitor are taken down, others would stop attacking him.

[✘]

The antivitruvians demand to be allowed to destroy statues in peace

I have a pretty good vocabulary but I actually had to look up the meaning of that word.

So you are a defender of the confederate "civilization" of which the statues are an example. Interesting.

No. I'm against destroying statues, particularly in graveyards. I also oppose the Taliban destroying statues of Buddha, yet I'm not a Buddhist.

You toss out terms like "traitor" and "racist" so often it becomes meaningless.

It's all just virtue signaling.

[✘]

Opinion Richmond’s Lee statue, after 131 years, is an unpardonable insult

Jeffrey Boutwell, a former resident of Spotsylvania County, Va., is a distant cousin of George S. Boutwell.

In the coming weeks, the Virginia Supreme Court will make known its decision regarding the fate of the most prominent Confederate memorial still standing in the nation: the 60-foot-tall equestrian statue of Gen. Robert E. Lee overlooking Monument Avenue in Richmond, former capital of the Confederacy.

Unveiled in 1890 , the Lee statue has stood supreme among the hundreds of memorials and monuments throughout the South honoring the Confederacy and its rebellion against the Union. By 1920, it had been joined on Monument Avenue by memorials to Confederate Gens. Stonewall Jackson and J.E.B. Stuart and President Jefferson Davis, making the street a pantheon to Confederate war heroes.

The dedication of the Lee statue occurred, ironically, on May 29, just days before Memorial Day, originally called Decoration Day to honor the hundreds of thousands of Union troops who died in the Civil War. In a ceremony described by one Virginia newspaper as “ the greatest day ” in Richmond history, more than 150,000 people celebrated with parades, cannons, fireworks and the singing of “Dixie” and “Carry Me Back to Old Virginia.”

Up north, the Boston Daily Globe provided extensive coverage of the event under the headline, “Immortal Lee.” In an accompanying editorial, the paper echoed the dominant theme of North-South reconciliation then common in the country, noting how “the gaping wounds of civil strife have now healed … [and] the past has lost its power to sting and wound.”

This would have been news to the nearly 4 million Blacks then living in the South and subject to increasingly harsh Jim Crow laws, lynchings and white supremacist violence. For them, “the gaping wounds” of slavery and the Civil War had not healed and the past had not “lost its power to sting and wound.”

The Boston Daily Traveler saw things quite differently. In an editorial entitled “An Unpardonable Insult,” the paper criticized the ceremony in Richmond for seeking to elevate Lee to “the same pedestal of honor and greatness” as George Washington. In blunt language, the paper contrasted the actions of these two native sons of Virginia, declaring that Washington would never “have engaged in a war for the destruction of the American Union in obedience to the action of Virginia,” as Lee did.

The Daily Traveler also noted an incident that was a premonition of things to come. At the ceremony, someone in the crowd placed a Confederate flag in the hands of a nearby statue of George Washington and “there it remained during the day” — similar to the “unpardonable insult” of a Confederate flag being carried into the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol building on Jan. 6 by supporters of President Donald Trump seeking to violently prevent Congress from certifying the results of the 2020 election.

I discovered an original of the 131-year-old Daily Traveler editorial among the papers of George S. Boutwell, a Massachusetts congressman who helped enact the 14th and 15th amendments in the 1860s guaranteeing political and civil equality to Blacks. After serving as treasury secretary for President Ulysses S. Grant, Boutwell was elected to the Senate, where he led an investigation of white supremacist violence in Mississippi . It’s little wonder that Boutwell would greatly sympathize with the sentiments of the Daily Traveler editorial.

By the time of the Lee statue dedication in 1890, it was apparent to Boutwell and the Daily Traveler that the proliferation of Confederate memorials was but a symbol of the victory of the Lost Cause campaign of the South in rehabilitating notions of white supremacy. The next several decades saw the spread of Jim Crow laws and the institutional racism, South and North, that has crippled our society well into the 21st century. Only now, sparked by the George Floyd murder and Black Lives Matter protests, is the United States beginning to seriously reckon with that legacy.

To give Richmond due credit, its city council made the decision in 2020 to remove and relocate all those Confederate memorials on Monument Avenue that were on city property. As the Lee statue is on property deeded by private citizens to the Commonwealth of Virginia, it is up to the state Supreme Court to decide its ultimate fate .

One day when someone else other than far leftists are in charge, someone will file a grievance over the George Floyd statue in Minnesota. Only a matter of time before that is taken down, and for reasons no one will be able to argue.

BTW. Congrats to Floyd on his almost 4 years of being drug free.

Would you like to comment on the seeded topic? That Robert E Lee was a traitor.

Is that why democrats loved him so that they merged his birthday with the Martin Luther King Jr. Holiday created by Reagan? Or did they just hate African Americans so much they couldn’t stand them have anyone of color celebrated?

“Would you like to comment on the seeded topic? That Robert E Lee was a traitor”

Quick question, why are you such a stickler about others staying on topic on your seeds when you go off topic on other posters seeds all the time? I don’t expect an answer and do expect this comment to be deleted because this is another one of those inconvenient truths. But if you think that hypocrisy goes unnoticed you’re wrong. And it’s not a good look, not at all.

because im not a troll

Do as i say, not as i do. Got it.

Maybe if the ones that got their panties wadded up never started attacking him and wanted to take his statues down for no good reason people would not have been put in a position of defending him.

[deleted]

Not becomes "worthless" - is already "worthless" - and boring.

Yet Jefferson, Jackson, Washington, Roosevelt and quite a few others still have statues standing.

Why is that?

The Democratic Chicago Times newspaper was one the nations' biggest critics of the Civil War. At one point, Lincoln thought that it was so traterious that he had it shut down.

During the 1864 election, Repubs found a new conspiracy, and accused Democrats of conspiring with Confederate spies to free Southern prisoners at the prisoner of war camp at Camp Douglas to disrupt the election.

That was two years after a race riot rocked the city after white teamsters prevented African Americans from using the public schools.

Damn segregationists, even today, most schools there are black or brown. White Chicagoans say not in my backyard. Maybe they are closer to Lee than they think!

You seem quite determined to try and rehabilitate Robert E Lee's reputation. Good luck with that.

There is no bias in the seeded article.

You on the other hand have made seven comments intended to blur the topic.

The bias I referred to was yours in your comments, not the seed.

No blur, an expansion of the topic for more clarity.

The article is not about Chicago during the Civil War.

next one will be deleted.

[✘]

[deleted]

I understand the positives of deleting uncomfortable truths.

[Or you have an issue with following directions... take the next two days to think about it.]

It would be nice if some of those commenting would stick to the article and if they disagree that Lee was a traitor present your case. If you think he was a traitor then you could give your reasoning as to why.

Even though I think that Lee was a very complicated person with some of his decisions being ''different'' I do think that he was a traitor. A very harsh accusation but IMO taking up arms against the US is simply without any flowers and BS is a treasonist action, plain and simple.

I think the article makes an extensive and persuasive case that Lee was a traitor.

I agree, it does.

Not really.

Remember those words.