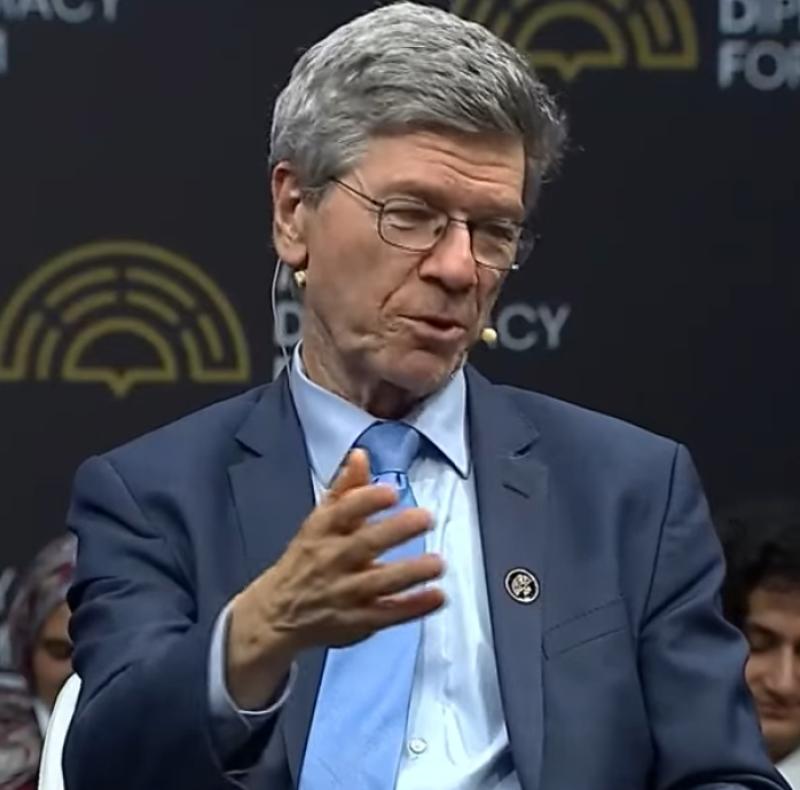

Jeffrey Sachs Goes Off, Roasts Donald Trump’s Trade Talk, Says 'Mickey Mouse Is Smarter Than Him'

By: Jeffrey Sachs, ET Now

For those who do not understand the problem with Trump's tariff actions.

Transcript

Uh, if you take your credit card and you go shopping and you run up a large credit card debt, you're running a trade deficit with all those shops. Now it would be pretty strange if you then blamed all the shop owners for having sold you all those things: "You're ripping me off, you're ripping me off, you're ripping me off. I'm running a trade deficit."

That is the level of understanding of the President of the United States. The trade deficit does not represent at all trade policies. It represents spending relative to production or earnings. We call that an identity. I teach it on the second day of my course in international monetary economics. Trump never made it to the second day.

So he says, "You're running a trade deficit. Look, they're all cheating me." But all that's happening is the United States is outspending its national income. And you can look at the national income chart. You can add up consumption and investment and government spending, and you can subtract off gross national product. And lo and behold, what will that equal? Not approximately—exactly—that will equal the current account deficit, which is the comprehensive measure of how much you spend on goods and services versus how much you sell in goods and services.

So the United States runs a current account deficit because it spends more than it produces. Why does it do that? We have a big credit card in the United States. It's called the national government. The U.S. government spends about $2 trillion a year more than it takes in in revenues. What it's doing is making transfers to the American people and to American businesses. It doesn't tax Americans for those transfers because—here's another little fact—the congressmen that vote on the budget got into office by being paid for their campaigns by rich people who don't like taxes.

So the political system says, "Spend, but don't tax us." So we run a chronic deficit in the United States. That spending goes out either as transfer payments or goods and services, and that's more than our national income, which is about $30 trillion, and our spending is about $31 trillion. And that's our trade deficit. And for that, Donald Trump blames the world.

Okay, I fail him for this. If he were my student, he's my president. It's a little weirder because when he did this in two days, the world lost $10 trillion of market capitalization.

By the way, where did it go? Uh, did it get transferred from here to here? No, it got destroyed. Why destroyed? Because trade—something also the President of the United States doesn't understand—is mutually beneficial. So if you stop trade, everybody loses. It's not that one side wins, the other side loses. He cannot understand that concept—as a guy that traded real estate in New York.

So his idea is somebody had to win, somebody had to lose. But what happened when he made this announcement was $10 trillion was wiped out worldwide. It's not that the U.S. went up and they went down—no, everybody went down, because the whole world system is based on a division of labor. And he's breaking that division of labor into pieces.

So then people said, "This doesn't make sense." Even the very rich people that gave him the money for him to get into office started saying, "This doesn't make sense." The hedge fund managers, who were his big campaign contributors, Elon Musk—who paid for his election, became prime minister—he said, "This doesn't make sense." And then the markets said, "This doesn't make sense." Not only $10 trillion, but as the finance minister said, interest rates started to rise because people began to dump U.S. Treasury debt—the safest thing in the world, apparently.

So, interesting what happened. It's not quite true that he reversed things. First, he left on this 10% tariff, except for one country—for China—145%, where he raised the tariff rates. That's because the United States has a deep neurotic attachment to China. The U.S. political system hates China. Why? Because China's big and successful. And so the U.S. hates it. It's a rival. It's a competitor. And so this is the one thing he left on.

Now, he's going to mess up everything with this too, because in a trade war between the U.S. and China, China wins. China does not depend on the U.S. market very much. It's about 12% of China's exports. China will do just fine. It's just dumb policy. There's no more—sorry to say it—there's just no more explanation to this than that. It makes no sense.

Now, it raises—if I could just one last point—how can this happen when it makes no sense? And that people should understand. We are in one-person rule in the United States. Our political system is in a state of collapse. What President Trump did is an emergency decree. Everything he does is an emergency decree.

Literally, you can go on to whitehouse.gov and then follow the menu to executive decrees, and there are dozens of them. And each one starts the same way: "With the powers invested in me as President of the United States, I hereby declare A: nonsense, B: nonsense, C: nonsense," because he's king.

Those powers are not invested in the President of the United States. They're invested in the Congress. You read Article I, Section 8 of our Constitution. It says that all duties originate with the Congress—and specifically in the lower house. All legislation has to start in the House of Representatives.

But the U.S., starting in 1945 after World War II, became a military state to a large extent. And so it sprinkled in its legislation: emergency, emergency, emergency. And Trump doesn't have to prove anything's an emergency. He just has to say something's an emergency.

So suddenly, the trade deficit became an emergency. And on that basis, he issues a one-person rule. Even his aides don't know what he's doing.

You raise one final interesting issue, which is that the market recovered about $4 trillion when he reversed. Anyone who knew that five minutes before made billions. This is not the cleanest government in the world. I can tell you, I'd be hugely surprised if some people didn't know just a bit ahead of time—starting with members of the U.S. Congress, by the way.

Look, we'll get into the more general issues about protectionism and the end of globalization in a minute. But I think what's happening—and the directives coming from the White House—are such a perfect example of what this panel is about. I'd just like to stay on this for a few more minutes.

Minister, is protectionism always a short-term aim, and does it always come at the expense of the longer-term gain?

Donald Trump hasn't said it in public, but apparently in private during his first term, he was asked about the problem of the U.S. national debt, and his answer was, "I don't care because I'll be dead by the time it's a problem." And apparently that's also his approach to the climate crisis.

So is this protectionism coming from the White House a short-term fix which is going to hurt America in the longer term in terms of how it grows?

It’s not a fix. It’s—uh—apparently a quick fix, but it’s fundamentally flawed, as the professor has very clearly stated.

Look, protectionism is nothing new. If you look at post–global financial crisis, the number of annual trade restrictions has gone up dramatically. In fact, like last year, there were over 3,200 trade restrictions. That is almost 11 times higher than what it was pre–global financial crisis.

So this has been a trend. But what we have seen over the past week or two is clearly a new level. This—this goes beyond, you know, some protectionist measures, trade restrictions—this goes into something—an all-out trade war. So that’s really worrisome, because if you go back again—I mean if you go—if you look at 20 years to global financial crisis, global annual trade growth was two times world real GDP growth rate. So in a way, trade was the engine of growth.

Now, that engine has been slowed. So if you look at post–global financial crisis, global trade growth barely kept up with, uh, real GDP—global GDP—growth. So that’s no longer really one of the, kind of like, strong engines.

But I think the way things are now—if, you know, if current state of affairs is sustained—we may end up, actually, with protectionism dragging global growth.

It is not only growth. It’s really—there are many, you know, additional fallouts from these type of policies.

Absolutely.

Yeah. Yeah. So the answer to your question: this is not a fix. It’s a fundamentally flawed, you know, policy perspective.

Obviously, countries have a choice. You know, they—they always have a choice. But we would rather, you know, see the world moving back to rule-based multilateral framework, you know, where everyone benefits.

I think—I agree with the professor—you know, over 1 billion people since 1990s have been lifted out of poverty—predominantly in Asia. I’m talking about absolute poverty here. And that’s largely thanks to, you know, trade and—and growth associated with that trade.

So it is worrisome that we are now experimenting with policies that may actually reverse some of these gains, which I think were very important.

A billion people out of absolute poverty cannot be underestimated. It’s quite significant.

Now, admittedly, trade does cause geographic dislocations. But the solution is not protectionism. The solution lies in more internal sound policies, you know, structural remedies. But also you can deploy tax policy, incentives, and other things to address, you know, dislocations in regions caused by, you know, global trade openness.

So it’s not a level. But protectionism will create more inequalities. It will create bigger problems. Already you've got significant headwinds for global growth: aging population, high global indebtedness, impending climate crisis. So protectionism is going to be yet another big blow to long-term growth outlook.

And that’s why growth is barely, you know, sustained at 3%.

I think the risk is that we will move to a new era where per capita GDP growth will almost disappear if we continue down this path.

Really interesting what you say about protectionism having fallout in other sectors. And we will get on to that—about how it might affect cooperation on the climate crisis, global health, etc., etc. But let’s use one country as a particular example about how a nation can react to protectionism.

So we have the U.S. tariffs, which in 90 days will come into effect beyond the 10% that Donald Trump has placed. Let’s take two rich countries: UK and Singapore will stay at 10%. Bangladesh and Botswana will both go up to 37%. Laos will be 48%. Syria will be 41%. Lesotho in Southern Africa will be 50%.

In 2023, the U.S. exported to Lesotho $7.33 million worth of goods. Lesotho in that same year exported to the United States $228 million. The U.S. GDP per capita in 2023 was $82,800 per person. In Lesotho, it was $916.

Gentlemen, how does a country like Lesotho deal with the protectionism coming from the U.S.?

Well, uh, look—protectionism is an external shock, meaning it’s not a decision by, you know, the counterparty. It’s—it’s essentially—so how do you deal with it?

I guess, uh, you focus on regional integration. I mean, as an antidote to protectionism. So regional connectivity, regional integration would be one way forward. So, you know, instead of globalization on a big scale, you focus on how you can deepen and broaden your ties with your immediate neighborhood or countries that are still willing to entertain rule-based trade.

So I think that’s the only way. Um, again, this is a major shock for many countries.

I think global supply chains are going to suffer. This will lead to—I mean, already I think—the risk is that capital will be misallocated. Take us—I mean, take Turkey for example. We are the world’s second-largest exporter of white goods. We need chips—basic ones. Nothing sophisticated. We’re not talking about four nanometers. We’re talking about, you know, 30, 40, 70 nanometers.

If we’re worried that countries are not going to supply that, even though it may not be the most efficient way, we may have to go into a very large capex to see if we could produce them.

We are good at something; other countries are better at something. So we would rather trade. And this is a very simple, you know, economics theory. Everybody benefits.

So I don’t think, you know, X country or Y country—there’s not much they can do except to look at ways in which they could mitigate the fallout from not being able to sell goods to the United States.

But professor, that takes a long time to arrange, because of course the shock is immediate. You can’t make deals that quickly, can you?

I think the particular tariff rates that Trump announced last week that led to that financial bloodbath are not going to come back. So I don’t think we’re going to hear again about those numbers after 90 days. Ninety days in U.S. time now is infinity—it’s eternity.

We’ll never hear those numbers again.

Where did those numbers come from? Something, again, so stupid you can’t believe that any country—any country—would do this.

But the idea is the following. As I said, if you want to know what your trade balance is—you earn some income. So you sell some services to somebody, and you buy things. And if you spend what you earn, you’re in trade balance—technically, you’re in current account balance.

Now most of us—I work for one employer, my university—so I run a big trade surplus with my university. And then I run a pretty big trade deficit with the grocery store that we buy our groceries from. And if I have to buy shoes, I run a trade deficit with the shoe store, and so forth.

Trump’s idea—just to add to the craziness of it—is that you should run a trade balance with everybody. Not an overall trade balance, but a trade balance with everybody.

So you should sell a little bit—you should work a little bit for your shoe store. You should work a little bit for your grocery store. You should go around—anytime you want to shop, you trade something. “I’ll write you an essay if you’ll sell me shoes.”

And you make your living somehow trying to balance your trade with all of your counterparts.

Well, this is insane. This is why we have a market economy. You don’t have to have balance with every transaction that you do with somebody.

But what Trump said was, “Oh, Lesotho—they sell us more than we buy from them, so they’re cheating us.”

That’s literally what he said. Literally what he said.

Okay—is it completely delusional or rhetoric?

It’s delusional. Okay, just so you know. It’s weird.

But anyway. Now then, he calculated a formula. “Okay, Lesotho—we have to tax them by the amount to reduce the imports from them so that we have balance with Lesotho.” And then they made some absolutely stupid formula that you would not accept in a first-year, third-week class.

It came out of the U.S. Trade Representative’s office. They probably were told, “Do it overnight, the boss wants it,” and then they came up with a list of tariffs country by country based on the bilateral trade balance.

You cannot make this stuff up.

This is not a—it used to be not a Mickey Mouse country—my country. But this is Mickey Mouse.

And I’m sorry—I apologize to Mickey Mouse. He would not do this. Mickey Mouse is smarter than this.

So we are in a crazy land, actually, with this.

Now, it stopped for a moment. We’ll never hear those numbers again.

I don’t know what we’ll hear in three months. God help us, really, because it probably won’t have to do with trade—it’ll have to do with something else.

But we can’t normalize this as “What’s the rationale? How to negotiate? What to do?”

Of course, 60 countries immediately said, “We’ll rebalance with you.”

And the President of the United States literally used the language I’m about to use—I’m quoting him, because otherwise I would never say this. He said:

“Sixty countries are coming to kiss my ass.”

He said that in a public speech—the President of the United States.

So this is—I’m sorry, I apologize, but it’s presidential language. Okay? I’m only speaking at high political terms.

So we cannot normalize this.

We have to say no.

We didn’t spend 100 years—or 200 years—2,007 years since David Ricardo put forward the idea of comparative advantage, okay? And we have been building the trade system since the ruins of World War II for 80 years.

And we have been building the World Trade Organization, which the U.S. led the creation of—I think it’s fair to say—for 31 years.

This should not be normalized—to try to figure out what is the theory of this.

And it’s a more fundamental point, ladies and gentlemen.

The United States is a rogue nation right now.

On many things.

Not just on trade, but on making Gaza into the U.S. Riviera. On whatever it wants to say.

It’s a little bit of a rogue nation.

For the world to hold together, the rest of the world has to say, “We’re not going down crazy lane. We’re going to be responsible. We’re going to go to the UN. We’re going to go to the World Trade Organization. We’re not going to get into this downward spiral.”

Because if we normalize craziness, there is no way out.

Uh, you mentioned Mickey Mouse, but there’s a kind of a theme here from Bloomberg—the news agency. These are its headlines in the morning and the afternoon of Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday.

Tuesday morning: “This is madness.”

Tuesday afternoon: “A clown show.”

Wednesday morning: “Stocks keep falling.”

Wednesday afternoon: “Could have been worse.”

Thursday morning: “Assessing the damage.”

Thursday afternoon: “Trump blinks.”

And, by the way, if I may—because it’s interesting, because I’m living in this crazy world—the Secretary of the Treasury then, with all deference to a person who has a very hard job, he says, “This was planned all along,” when Trump dropped this.

Can you imagine? He couldn’t say anything else though.

Well yeah, I know—but to hear this from your Treasury Secretary is not also reassuring, because all you hear is a crazy land, rather than what we need to hear, which is rationality.

Okay, so let’s make it more general for the moment—and by the way, ladies and gentlemen in the audience, I’ll give you a few minutes at the end if you want to ask our two panelists a question. We’ll try to get a few questions in from the audience.

So to broaden it out—

Minister, as the professor says—and pretty much everybody agrees—protectionism doesn’t make economic sense because, in the longer term, it’s going to cost everybody. So what’s driving increasing protectionism—not just in the United States but in other nations as well? Because if it doesn’t make economic sense, does it then become a political statement from the person imposing that protectionism to almost appear as a nationalist moment, to bring people toward that decision maker politically rather than economically?

Well, it’s easy to explain. I think what is driving the current, you know, what seems like a fundamentally flawed set of policies is—first of all, let’s set the scene. I mean, there’s a geostrategic competition between China and the United States. We know that.

China has what it takes to become a superpower, because it has human capital, it has state-of-the-art infrastructure, and now it’s catching up in technology.

The United States considers itself as the hegemon power. So we know from history there’s always been tensions between existing superpowers and emerging ones.

It doesn’t have to end this way—meaning in a trade war or any other force—but it does. In the past, I mean, history tells us that we more frequently see tensions rather than cooperation.

So what lies behind this? Very simple.

Go back 20 years ago, roughly speaking—China accounted for about 8% of global manufacturing. Today, China accounts for more than 30% of global manufacturing.

Who lost ground? United States, European Union, and Japan.

United States clearly also sees this. Again, go back to 20 years ago and just visualize a world map. Which country commands as the main trading partner of the rest of the world? Maps are all over the place.

Clearly, it was the United States 20 years ago. Today, it’s China.

Now normally, the way you would respond—the way I would respond—is that, “Look, we need sound policies, structural reforms to regain ground.”

Instead, it looks like this rivalry—combined with lack of, obviously, clear understanding—leads to going after quick fixes.

And quick fixes, which are also to do with populism, nationalism, is to blame others and to present it in a simple fashion.

The reality is—you have to be more competitive. You have to invest in upskilling, reskilling your population. You have to invest in your infrastructure. And you have to—you know, there’s a long list of homework.

But those are politically difficult to deliver. They take time. And they’re difficult.

So structural policy has been lacking in most countries. And when you can’t deliver structural transformation, then you go—either you rely on monetary policy to fix things (you know, monetary policy in many parts of the developed world has been doing the heavy lifting over the last couple of decades in the face of difficulties).

So my point here is that I think we know what drives it: it’s losing ground.

But how do you regain ground?

Again, the sophisticated way would be to do the right thing and deliver on reforms.

The easy way would be to blame everyone else and come up with high tariffs as a fix.

Let’s see.

Okay, so protectionism is also not helping your friends—to concentrate more on yourself rather than the outside world.

We know that the dramatic, drastic cuts to USAID—the Agency for International Development—has already, or is going to, cost lives.

Myanmar’s recent earthquake—the Americans have been for decades maybe the most important first responder, sending hundreds of rescue workers. They sent three administrators. They didn’t send a single rescue worker.

They laid off recently some people working for the federal government on the U.S. nuclear program. They realized very quickly, within a couple of days, that it was actually a national security issue. So they were told to come back to their office.

The office said, “Sorry, they’ve been excluded from their federal email, so we can’t get in touch with them.” So they couldn’t re-employ them.

Professor Sachs, when you were president of the Earth Institute at Columbia University...

It focuses—I’ve got to read this from the notes—it focuses on sustainable development, this institute at Columbia, including research in climate change, geology, global health, economics, management, agriculture, ecosystems, urbanization, energy, water—everything that we need to live.

So how does protectionism affect these kinds of relationships between one country and another country?

Yeah, I want to answer that by continuing on with the brilliant explanation that the minister just gave about the hard stuff and the easy stuff.

So, just to say—in American politics, the swing states in the presidential elections in the last three elections in particular have been the Midwestern states. So those are states like Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Minnesota.

These are states that can go either way. And those states did suffer a decline of employment in manufacturing—not only or even mainly because of trade, but also heavily because of automation over the last 40 years.

I come from Detroit, which is Motor City—used to be—and I used to go, when young, on school field trips to see the assembly lines. And there were actually workers on the assembly line. But now, if you go to an automotive plant, it’s all robots. Very, very few people inside.

That’s not because the jobs went overseas in that case. That’s because the assembly line itself became an automated phenomenon.

So Trump is giving an answer to those swing states: “It’s China’s fault. It’s Mexico’s fault. It’s Lesotho’s fault.”

What the minister said is really important. That—when he said that trade benefits the economy, but it could hurt some sectors. And what you do is not stop the trade, but you make sure that you pull everyone along—maybe in a regional policy, or maybe in job reskilling, or maybe in some other kind of public investment or education policy.

Here’s where the U.S. really failed over the last 40 years. We let the inequalities widen and widen—partly because of automation, partly because jobs did go overseas—but for the right reason. They had comparative advantage in those jobs. Skilled people got better and better salaries. Lower-skilled people had their living standards fall.

The gap widened. By the way—not just the income gap. The life expectancy became 10 years or more.

So many of our epidemics, so many of our social problems relate to this widening inequality. The United States political system didn’t address it at all—for 40 years.

And that comes to what I mentioned—the corruption of the political system. When candidates of both political parties are paid by rich donors for their re-election campaigns, and both parties then become the agents of tax cuts and no real addressing of the social conditions—you end up with a Donald Trump coming in and selling a pseudo-explanation: “It’s all China.” And selling a pseudo-remedy: a trade war.

What the autoworkers are going to learn right now is they’re going to lose jobs by even the tariffs that have been put in place—because we need the intermediate parts brought in from elsewhere. Now they face higher costs.

And the United States can’t compete at all with Chinese electric vehicles. China—the United States has basically handed China the electric vehicle market for the next 20 years. So did Europe, by the way. Europe delayed the transformation to electric vehicles. Said, “We produce great internal combustion engines—we’re going to continue to do that.”

The world actually needs electric vehicles because of the climate crisis.

So all of this is to say—the real hard work is to think ahead.

The country, by the way, in my experience of working all over the world in the last 40 years that thinks ahead the most—is China.

China’s success is not random.

China’s success actually is a lot of forward-looking planning.

In 2014, China issued a document called Made in China 2025. And it wasn’t a protectionist policy—it was, “We need to invest in the technology so we can be at the forefront.”

I think in eight of the ten sectors that were identified there, China succeeded in reaching the forefront.

In 2017, China made a plan for artificial intelligence—this is already eight years ago. DeepSeek didn’t just come out of nowhere—it came out of a long-term strategy.

So this is hard work that actually pays off.

This is what every government should do. This is what every country should do—is look ahead.

Now, you mentioned a very interesting idea—we got a president who doesn’t understand and maybe doesn’t care about the future in the same way.

But just to say—the biggest issue on the planet should be the climate crisis—not all the things we’re endlessly talking about. And every part of the world is going to suffer terribly by what has been built in—terrible, very dangerous climate change.

It’s out of the headlines—but you know, I had a very difficult job. I was the director of an institute with 300 climate scientists for 14 years—some of the world’s leading climate scientists.

The reason it was a hard job is that every week they came up and told me, “It’s worse than we thought.” They would give me endlessly grim news.

And the lead climate scientist at Columbia University is a man named James Hansen, who I regard as the world’s leading climate scientist. And he produced a study in January that said: “It’s much worse than we had thought. The world’s temperature has gone up by 0.3 degrees Celsius in three years. We have had 21 months of the last 22 above 1.5°.”

That’s the new baseline, by the way. That’s not because of an El Niño effect. That’s the new baseline. We already blew the limit that we set 10 years ago in Paris—that we said we would not exceed. We’re already above it.

And what Hansen says is—we’re rising at an accelerating rate. Now the average rate is probably between 0.3 and 0.4 degrees Celsius per decade now—on average.

So we’ll be at 2° excess.

What all of this means is profound danger—20 years from now, 25, 30. But we’re already seeing terrible danger today.

I don’t want to minimize what’s already happening. Los Angeles burned down. Massive forest fires in Korea last week. It’s everywhere.

My wife and I are non-stop traveling. Every single place we go is some kind of climate crisis. Literally—in some it’s a drought, it’s floods, it’s heat waves, it’s pest infestations, it’s forest fires.

And the sea level is going to rise by many meters, which is not great for Istanbul, by the way—and not great for coastal areas. It’s very dangerous, what is built into the system now.

What is Trump’s answer for this?

Yesterday, King Donald issued an executive decree to bring back coal.

It’s willful destruction of well-being. Willful.

And that is—again, he pulled out of the Paris Agreement.

What I’m hoping, ladies and gentlemen, is the other 192 members of the UN have to say, “No. We’re not entering a crazy land. We’re going to take care of our future right now.”

I live in a crazy land. But the rest of the world has to avoid the crazy land—has to avoid normalizing this.

I don’t know if any of you saw it—during the height of the coronavirus pandemic, an Australian cartoonist drew a cartoon which had the first tidal wave, kind of a tsunami, of economic recession.

There was a bigger tidal wave tsunami behind it, which was COVID-19.

And then a huge one over both of them—which was the climate crisis.

So get ready.

I’ll give you a chance to ask a few questions, but I just wanted to address one final issue to the minister—and I was getting a bit depressed, professor, when you were talking about that.

I tell my kids, since they were born—they’re now 21 and 19: "Live anywhere you want in the world, but don’t live near the coast or near a river."

The professor is saying that the climate crisis is going to be one of the—probably (I’m kind of, you know, putting words into your mouth, professor)—that deglobalization, if it becomes more and more of a popular sentiment and policy, the climate crisis will be affected because of a lack of cooperation through deglobalization.

Minister, what other big dangers do you see if the trend of deglobalization gathers pace?

Well, as I mentioned earlier—in addition to the impending climate crisis, which could have a devastating impact on the future of humanity—I think we are faced with significant headwinds that already exist. But some of them could become more complicated.

One of them is high global indebtedness.

If protectionism, you know, clearly goes the way it is today—meaning if we really go into these trade wars—and if this leads to higher inflation, even for a couple of years, if that’s the case—then that means long-term interest rates are likely to rise.

And if that is so, then many countries that are already struggling to manage their debt service, you know—global indebtedness, if you look at it overall—indebtedness was 328% last year. Three hundred twenty-eight percent of GDP.

Yeah. This is huge—when interest rates are very low.

But when rates go up, clearly that’s a big issue.

I mean, look at—you know, look at the Turkish scene. Yes, we’ve had a, you know, domestic—you know, I mean, domestic issue that led to some market turbulence.

But what happened post–April 2? CDS have gone through the roof. CDS are counter-risk premium. You know, our external bond yields—10-year, 5-year—they’ve all gone up significantly on the back of these tariffs.

I think there are already many countries, according to the UN, that pay more in interest on debt than what they are able to earmark for education and healthcare combined.

So I think, you know, we already have issues such as indebtedness that could—the current, you know, trend could exacerbate.

I mean, aging population already could create huge constraints on public finances going forward.

So those are some of the additional headwinds that exist—that could actually serve as a speed limit or a drag on growth.

So I think, you know, the world—and I agree with the professor—the world has to, you know, rather than going down this path, we need to cooperate more. We need to work more closely on climate change, on how to address other problems.

Because protectionism will also lead to probably global inequalities. You know, if you don’t allow AI chips to be freely available to everyone, clearly that’s a big issue.

Because then many countries will be left behind in terms of tapping this—you know—AI that has immense potential to boost productivity.

You know, protectionism is not limited to trade of goods and services. It’s now associated with financial flows, you know, with diffusion of technologies through FDI.

So clearly, I think we’ll be worse off unless we cooperate—unless we return to multilateralism.

But sadly, right now, it’s all about a shift to minilateralism—you know, a few countries getting together. But that’s not enough.

I think issues are too big for a few countries to address. I think, you know, the rest of the world should come together.

Audience Q&A Segment Begins

Yes, there are significant challenges.

When you mentioned aging population—I have a good example from Europe.

Only two countries on the entire continent are having enough babies to sustain their population level. That’s Ireland and Portugal.

So you imagine the pressure on the taxation system and the spending on those other countries that are not sustaining their population levels—and are just getting older and older and older.

Okay, let me look at the back as well—if anybody has any questions. We’ve got about seven minutes left. And please—make it a question, not a lecture. Because if it’s a lecture, I’ll have to stop you.

Gentleman over there, and gentleman over here.

Okay, please introduce—oh, there’s a microphone, thank you very much.

Audience Member 1:

Doesn’t work—yeah, it does work. Okay, thank you very much.

I have a question for Mr. Jeffrey Sachs. My name is Sarcer, and I’m from Haraji News.

So you mentioned that we shouldn’t look for a rationale behind the actions of Donald Trump. But just to be a devil’s advocate—I just want to understand their point of view, which they mention: yes, trade deficit and the national debt of the United States, but also they mention the hard industries that left the United States back in the day.

So, what I’m trying to understand is—if the United States gets into a confrontation with global powers such as China or Russia or any other state—maybe even Europe one day—is it wrong for them to want their hard industries back?

And this is their rationale to put these tariffs on, because Donald Trump mentioned that we are buying cars from Canada that we could have been producing before.

So is there a rationale behind—at least on the hard industry part?

Jeffrey Sachs:

Yeah, you know, in trade theory or trade concept, there is the national security rationale. So you may want to procure domestically to have an armament industry.

That’s quite different from imposing tariffs on 150 countries in a completely arbitrary way. In fact, the right policy might be local procurement from domestic industry—that has nothing to do with trade policy at all.

So that is not an argument for what he’s doing.

But I would add one more point—we don’t need an arms race. And we don’t need a war.

Actually, diplomacy is really cheap compared to war. That’s why we’re at the Antalya Diplomacy Forum—not the Antalya Military Forum.

So if Trump really wanted to save some money—we have almost 800 overseas military bases in 80 countries. This is crazy.

So if you wanted to save money and close the budget deficit—I would close hundreds and hundreds of military bases, and leave all these countries at peace. Because wherever there’s an American military base, there’s a big headache. Believe me, sir.

Moderator:

Okay—is your question to the finance minister? Is your question to the finance minister or to the professor? Because I want to even things up. I would come back to you if it was for the professor, but if you—

Audience Member 2:

Okay, let’s address it to the finance minister.

Audience Member 2:

One, two, one, two. My name is Realel Miller, formerly of the OECD, formerly of UNESCO, and formerly an adviser to finance ministers—so I can address my question to a finance minister.

One of the things that’s tremendously tempting—and it was really in part what the last question was about—was the hard industries, right?

So now let’s go back to being an extractive economy. Coal mining, you know. In Canada—I’m Canadian originally—beaver skins, right? That we sent over. So, resources.

Right now, we have seen in the past, historically, when there was a move from natural resources to manufacturing, it was quite difficult for the society and the politics to change. Because the oligarchs of resources were not the oligarchs of manufacturing.

So I have a question which relates to the historical context we’re in: what if we’re moving to intangible economies?

What if we’re moving away from tangibles in general? And those robots are going to take care of producing intangibles?

How do we talk to people who are nervous and worried because they’re accustomed—

I go to Germany, and I say, “Can Germany be rich without producing cars?” And they go, “Never.”

I say, “Could Britain be rich without producing coal?” “Never.”

And so we have this historical difficulty of making the transition. And I wonder what you can say in a country like Turkey, where you are making the transition through industry—and China through catch-up and convergence—but can we begin to talk about going beyond the tangible economy?

Finance Minister:

Of course we can imagine. Because if you look at the last couple of hundred years, there have been significant trends.

I mean, if I’m not mistaken, if you go back 200 years ago, 90% of employment was in agriculture. Today, in the developed West, it’s about 1%, 2%. But we are much better off.

So I think we can extrapolate.

It’s true that we may achieve artificial general intelligence soon—meaning within a year or two. And, according to experts, maybe artificial superintelligence within five years.

And assuming that also gets converted in robotics and advanced manufacturing—chances are the traditional employment will no longer be there.

So we have to come up with obvious—

That’s why I think, you know, it seems like today’s debate—considering what is ahead of us—is a bit outdated.

So, I hear what you’re asking. And it’s really complicated. We all have to think.

I remember attending a Global Economic Symposium in Kiel back in 2007. And one of the sessions—because I was finance minister and, you know, well, treasury—they put me in that session, in that panel. And the question was: “When do we start taxing robots?”

So look—yes, I do see that happening. I don’t have the answer. But certainly, we have to think about it.

Moderator (light-hearted):

It’ll be interesting to know if a robot will need a work permit as well, right?

Moderator:

Okay, that’s it. The time is up, ladies and gentlemen. It was always going to be too brief with these two particular gentlemen.

I have to wonder what score Trump would earn on a test of US Civics.