War of the States

By: Steven Melanga

Nowhere is the dichotomy between how red and blue states have handled Covid more obvious than in even a cursory glance at how Florida and New York handled the pandemic, a dichotomy I call the tale of two states .

Earlier this week, Stephen Moore wrote on internal migration in America:

War of the States

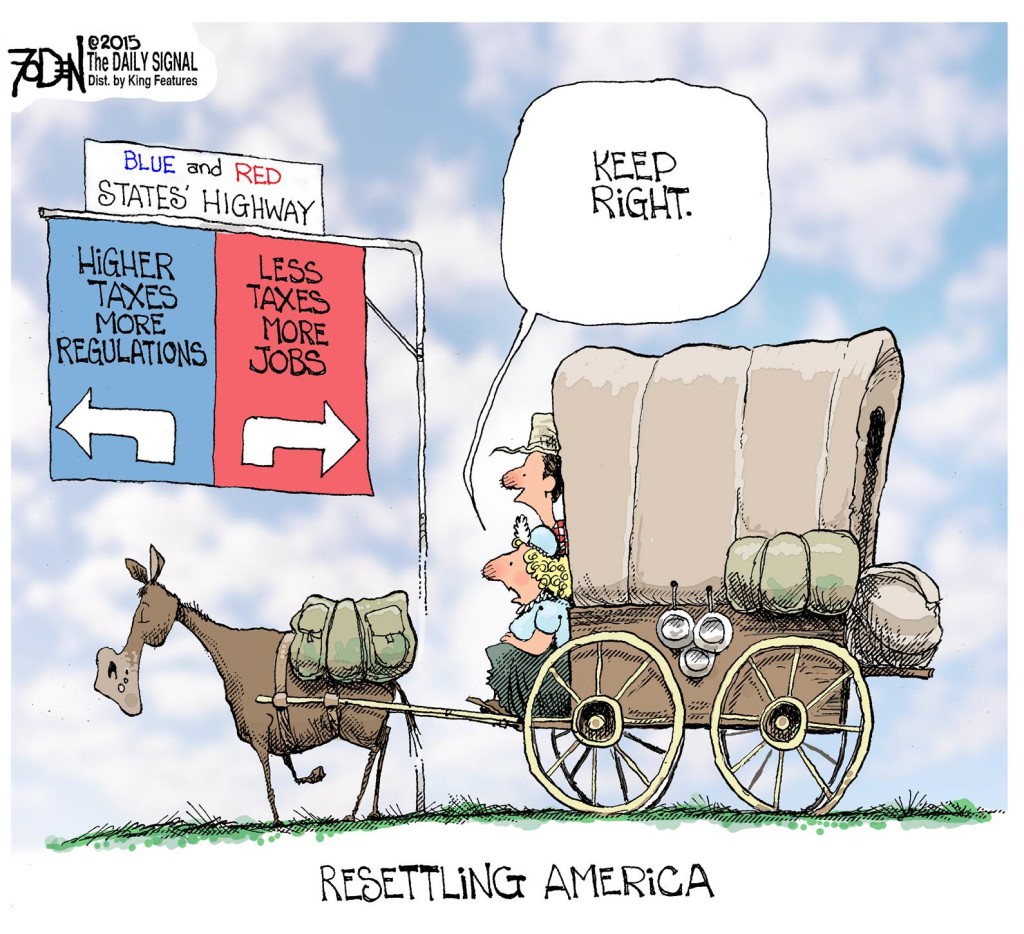

In a battle for jobs and people, Republican governors challenge the Biden agenda with tax-cutting and deregulation.

Steven Malanga is the senior editor of City Journal and the George M. Yeager Fellow at the Manhattan Institute .

I n 2009, facing a revenue drop-off from the previous year’s recession, states raised taxes collectively by $29 billion—at the time, the largest annual hike in history. Many of the biggest increases occurred in Democratic-leaning states, including New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, which targeted businesses and upper-income residents especially, even as newly inaugurated president Barack Obama touted a similar agenda in Washington. What seemed like a new taxing trend dissipated, however, after the 2010 midterms, when Republicans captured seven governorships and full control of 23 state governments, up from just ten before Obama’s election. The newly elected governments quickly began cutting taxes and reducing business regulations, setting off an intense, often acerbic, state competition to attract wealthier residents and employers. This battle transformed the American economic map, right up to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Now, with another pro-tax Democrat, Joe Biden, in the White House and a lockdown-induced recession in the rearview mirror, another clash among the states is breaking out. Several Democratic strongholds, claiming fiscal stress and the need for “equity” in taxation, have initiated big increases on individuals and firms. Meantime, a group of largely Republican-leaning states have cut levies. The rise of remote work and the vastly different Covid strategies that states have adopted have added unique elements to this conflict. The Biden administration has also joined the fray. Having learned from the Obama years how effective the GOP strategy can be, Biden is trying to blunt some Republican state economic policies through federal mandates. But only a year after Biden’s victory, Republicans have already won the governorship and legislative control of one solidly Democratic state—Virginia. The battle over states’ futures will intensify in the run-up to November’s elections, with 36 governorships and more than 6,000 state legislative seats in play.

I t’s hard to overestimate the influence that the 2010 state elections had on America’s political and economic landscape. Republicans went from complete control of just one-fifth of state governments to nearly one-half, and that momentum kept building until the GOP had won 33 governorships by 2016. The party also gained a remarkable 900 additional state legislative seats.

The policy results : tax cuts, regulatory reform, and constraints on the growth of government spending—sometimes in surprising places. After New Jersey elected Republican Chris Christie in November 2009, he and a moderate Democratic legislature cut the state corporate tax and capped the rise of local property taxes. Michigan Republican Rick Snyder, elected governor in 2010, scrapped the costly Michigan Business Tax, an old-fashioned levy on gross receipts, and replaced it with a modern, less onerous corporate income tax. Later, Snyder reduced personal income-tax rates. Maine’s Paul LePage reduced corporate and individual income taxes and eliminated taxes entirely for 70,000 low-income families.

Republican governors also battled unions to slash costs and ease regulations. Indiana’s Mitch Daniels, facing opposition from government worker groups for his efforts to reduce spending, rescinded, via executive order, the right of public employees to bargain over his reforms. In Wisconsin, Governor Scott Walker caused a national furor when he enacted legislation to end public unions’ ability to bargain collectively over benefits. The law also let government employees opt out of union membership. Among other changes, the measure nixed a sweetheart deal that the state’s teachers’ union had negotiated requiring local school districts to buy health insurance at uncompetitive rates from a union-controlled firm.

The regulatory face-off extended to private unions. Over five years, beginning in 2012, five states passed right-to-work laws ending mandatory unionization and allowing workers to opt out of membership in labor organizations, bringing to 27 the number of right-to-work states. What prompted that flurry of lawmaking—the previous five states to adopt right-to-work measures took nearly a half-century to do it—was the growing perception that companies were becoming reluctant to locate jobs in states that forced unionization on workers. Indiana’s Daniels, who previously had displayed little interest in right-to-work legislation, signed such a bill in 2012, his final year in office. “During the debate, which was very contentious, I was urging both sides not to overreact or exaggerate,” Daniels said . “But I may have underestimated the impact. We have had a flood of calls and inquiries [from businesses], starting literally the day I signed the bill.” Nearby Michigan and Wisconsin soon enacted similar legislation.

A right-to-work environment has become a key factor in location decisions for industrial companies in particular. Right-to-work states accounted for nearly 70 percent of manufacturing’s jobs recovery from the recession through 2019. Indiana gained 50,000 manufacturing jobs from the time of its right-to-work conversion through 2019. Its next-door neighbor Illinois, once the Midwest’s manufacturing powerhouse but a required unionization state, added just 6,000 jobs over the same period.

The impact of right-to-work has become even clearer over the longer term. A study by consulting firm NERA of economic growth over 15 years in right-to-work states found that private-sector employment expanded in those locales by nearly 27 percent from 2001 through 2016, compared with 15 percent gains in other states. Personal income rose by 6.3 percent in right-to-work states, compared with just 0.2 percent in other states. Even during downturns, right-to-work states proved better at retaining jobs than other states, the study found. No wonder, then, that these states keep attracting investment. Recently, Ford and a foreign partner agreed to spend about $11 billion to build two electric vehicle battery plants in Kentucky and an assembly facility and battery maker in Tennessee, which collectively will employ more than 10,000. General Motors is spending $2.8 billion on a new Tennessee plant, while Volkswagen is investing $800 million to expand its facility in the state.

T he state battle over jobs has become intense and sometimes personal, as Republican governors from pro-business states now openly woo firms and residents from Democratic states. When Texas ran provocative radio ads in the Golden State in 2013, inviting businesses to move South, then–California governor Jerry Brown derided the effort as “barely a fart.” The media jumped to California’s defense, with the Sacramento Bee editorializing about Texas’s high rate of prisoner executions and low rates of health insurance.

“In 2020, firms announced 781 new projects in the Lone Star State, compared with just 103 in California.”

Despite such dismissals, poaching GOP states have benefited at California’s expense—especially recently. A new study by Stanford University’s Hoover Institution found that the persistent pace of companies relocating out of California accelerated during the pandemic. From 2018 through mid-2021, 265 California firms moved operations out of the state, with those in Los Angeles and San Francisco Counties leading the way. Over more than a year of harsh lockdowns in California, the study found, monthly relocation announcements had doubled. Only 27 of the businesses tracked by the study, moreover, moved to states that are not right-to-work. Instead, places like Texas, Tennessee, and Arizona have grabbed the most California exiles. Though derided by the Bee , Texas was overwhelmingly the preferred destination, attracting 114 firms, including blockbuster moves by Oracle and Hewlett Packard Enterprise.

Texas has also vastly outperformed California in drawing new investment, as tracked by Site Selection magazine. In 2020 alone, firms announced 781 new projects in the Lone Star State, compared with just 103 in California. None of this is surprising if one listens to what company executives say about business conditions, particularly now. Asked by Chief Executive during the pandemic where they were most likely to locate new facilities, the top officers at America’s biggest companies selected Texas as the top destination , with California mentioned least often. Right behind Texas were Florida, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Indiana. The executives mentioned taxes, regulations, and availability of talent as key factors in their decisions, but how states handled Covid also mattered significantly. Virus lockdowns, the magazine noted, made executives “an increasingly restless bunch,” open “to all kinds of new ideas about how—and, more to the point—where to do business.”

States that remained more open for business tended to rise in executives’ estimation. South Dakota, for instance, improved 12 spots from the previous magazine poll. “We’ve been free to operate as we choose, not just through the pandemic, but long before as well,” Travas Uthe, the CEO of Trav’s Outfitter, in Watertown, South Dakota, told Chief Executive . Blue states like Rhode Island that were more open than their neighbors also benefited.

The struggle over Covid restrictions between executives and state officials sometimes turned nasty. Early in the pandemic, Elon Musk denounced California’s decree that shut his Tesla manufacturing facility in Fremont as “fascist.” Musk is now building a new Tesla facility in Austin and located his high-profile space-exploration venture, SpaceX, in Brownsville, Texas. (See “ Liftoff in Brownsville ,” Spring 2021.) Recently, he announced that Tesla’s headquarters would move from California to Texas. Memories of extreme Covid restrictions may last for years, one relocation expert told Chief Executive . “States that had strong and balanced leadership during Covid will probably be the best positioned for short- and long-term economic growth.”

Technological adjustments that companies made during Covid lockdowns are adding new twists to relocation battles. Remote work gives businesses far more flexibility in where they put jobs, which will almost certainly make executives more inclined to consider low-tax, low-regulation places. A recent Moody’s Analytics study looked at concentrations of jobs in industries where employees are most likely to work remotely—including finance and business services—and ranked cities by such factors as quality of life and cost of living. The winners in this new work world, Moody’s suggested, will probably be small and midsize cities in the South and West, while the losers will be big northeastern cities—including New York and the greater Washington, D.C., metro area. Similarly, office-occupancy numbers in major U.S. cities during the pandemic have consistently shown that workers were far less certain to be in the office in the biggest downtown markets, like New York, Chicago, and San Francisco, than on average in other cities.

Partially in response to remote work, smaller cities with a high quality of life are shifting economic-development priorities from attracting companies to attracting their employees. Chattanooga and Tulsa, for instance, have begun offering remote workers up to $10,000 to relocate. Some developers in places like Ogden, Utah, are even embarking on combined residential/commercial projects designed to attract remote workers. And it’s not just northeastern cities that this realignment threatens. Recently, venture capitalist and Democratic strategist Bradley Tusk wrote that Silicon Valley firms looking to exit California are eyeing cities in Republican-governed states, including Texas, Arizona, Tennessee, and Georgia. Though some cities in these states, like Austin, are progressive politically, Tusk noted, low state-tax rates are a big attraction for firms.

I ndeed, tax cuts remain a powerful tool to entice people and firms, and the pandemic has triggered a new tax war. After the lockdowns, states and cities predicted unprecedented revenue drops. One estimate put state-tax losses at $150 billion in fiscal 2021. California projected a $40 billion shortfall. Instead, economies bounced back quickly from the pandemic, partly because of widespread adoption of remote work and extensive federal aid from the Trump and Biden administrations—hundreds of billions of dollars in unemployment benefits (which kept individuals spending money), business loans, and funding for local governments to fight Covid. The March 2021 Biden stimulus then provided local governments with an unprecedented $350 billion to bolster their budgets. The revenue gusher has produced state budget surpluses where experts had only recently predicted steep deficits.

Nearly a dozen states, mostly Republican-governed, have used the windfall to cut taxes. Idaho reduced its corporate and individual tax rates and shrank its income-tax brackets from seven to five, producing a $163 million tax cut for residents and businesses. The state also sent $220 million in rebates to everyone who filed tax returns in 2019. Iowa used its unexpected surplus to push forward already-planned tax cuts, saving taxpayers $298 million next fiscal year. Governor Pete Ricketts signed legislation cutting Nebraska’s corporate-tax rate twice over the next two years. Ohio dropped its top income-tax rate and raised the minimum level at which lower-income residents must pay taxes from $21,100 to $25,000—providing tax relief at both ends of the income spectrum. Other states lowering taxes included Arizona, Wisconsin, Louisiana, and Oklahoma.

These moves may be only the beginning of the tax-cutting wars. Several Republican governors have said that they want to eliminate their state’s income tax eventually. West Virginia’s Jim Justice, reelected in November 2020, argues that ending the tax is necessary to reverse the state’s population decline and spur new investment. He’s angling for phased-in cuts, starting with a 60 percent reduction, until income taxes are gone. Republican legislative leaders in Mississippi are looking at something similar, backed by Governor Tate Reeves. The aim, Reeves has told the press , is to help Mississippi compete with other no-income-tax states like Texas and Florida, whose economies have been booming. Currently, seven states have no income tax, and two others—Tennessee and New Hampshire—don’t tax wages.

Count Virginia’s new Republican governor, Glenn Youngkin, as another potential tax-cutter. Though the fight over parents’ education rights drew the most national attention during the state’s November 2021 election, voters said that the economy was the biggest issue , and taxes ranked third, after education, in importance. Youngkin’s agenda includes tax cuts that he estimates would save the average household $1,500 a year, including eliminating the state sales tax on groceries, suspending gas-tax hikes for a year, cutting income taxes by doubling the standard deduction that Virginia filers can take, and requiring that voters approve local property-tax hikes. His chances of enacting these items improved substantially after Republicans also retook Virginia’s state legislature, part of a statewide GOP sweep. That victory, moreover, means that Virginia will remain a right-to-work state for the foreseeable future. Democratic gubernatorial candidate Terry McAuliffe, by contrast, had criticized right-to-work.

Former governor Rick Perry sparked controversy back in 2013, when he tried to lure businesses to Texas in ads that ran in Democratic states. (ERIC GAY/AP PHOTO)

Former governor Rick Perry sparked controversy back in 2013, when he tried to lure businesses to Texas in ads that ran in Democratic states. (ERIC GAY/AP PHOTO)

T he Republican moves contrast sharply with those of Democrats in high-tax states. Despite $12 billion in Biden stimulus, New York heaped a $4.3 billion new tax burden on residents, largely focusing on the wealthy. Several other blue states tried to raise taxes, only to be thwarted by residents. Illinois governor Jay Pritzker lobbied for a $2 billion tax increase, which would have required changing the state constitution, but voters soundly rejected the idea in November 2020. A California ballot initiative, which would have rolled back provisions of the 1978 Proposition 13, resulting in an estimated $12 billion tax increase on businesses, was similarly rejected by voters, despite the backing of key state Democrats. Now, Massachusetts Democrats seek their own $2 billion hike via a ballot initiative asking voters to approve a graduated income tax so that legislators can raise levies on upper-income residents.

The next battleground may be unemployment taxes—a significant cost for many firms. The spike in lockdown-caused joblessness has drained state unemployment trust funds. As of early 2021, the funds in 37 states had fallen below minimum levels , as determined by the U.S. Labor Department, and 22 states collectively had to borrow some $45 billion from the federal government to maintain payments. Now the bill is coming due. While some states, including Ohio, Virginia, Arizona, Utah, and Nevada have used Biden stimulus money to replenish their funds, several Democrat-led states, including New York and New Jersey, have opted to direct all the stimulus into other spending and set big increases in taxes on businesses. New Jersey, for instance, boosted its unemployment taxes by 20 percent, or $252 million, in 2021, part of a series of phased-in increases. New York businesses, for their part, face hikes ranging from 26 percent to a staggering 160 percent of previous tax rates, according to state comptroller Thomas DiNapoli .

Advocates for higher taxes often say that the levies don’t drive away wealthy individuals or businesses. When New Jersey raised taxes on the wealthy in November 2020, Democratic governor Phil Murphy said, “When people say folks are going to leave, there’s no research anywhere that suggests that happens.” Yet New Jersey, with taxes on the wealthy and on businesses long ranking among the nation’s highest, ranked a dismal 42nd in economic growth over the five years preceding the pandemic, according to one study, and it has been an economic laggard for two decades. Voters in this overwhelmingly Democratic state showed their disapproval in giving incumbent Murphy an extremely narrow victory in his November reelection bid. Polls showed that most voters favored the Republican position on cutting taxes over Murphy’s.

True, other factors beyond taxes, such as workforce quality, can drive economic gains and business-location decisions, but what high-tax advocates ignore is that fiscal policy doesn’t exist in a vacuum. High taxes typically reflect a philosophy of government that also imposes heavy regulations, which raise the cost of living for residents and the cost of doing business. In fact, virtually every state that ranks among the highest-taxed —including New York, New Jersey, California, and Connecticut—shows up among the top ten in regulatory burden and overall cost of doing business, too. The inhospitable climate drives away businesses and residents alike.

O ne key progressive regulatory issue increasingly affecting business is the expensive effort in places like California and New York to move away from fossil-fuel power before alternative-energy supplies are reliably available and affordable. To meet state-imposed mandates for renewable energy, California utilities have invested heavily in new generating projects, and passed the cost on to consumers. Even before recent spikes in worldwide energy prices, rates for Californians were soaring . Between 2011 and 2019, energy prices rose by 30 percent in the Golden State, while remaining flat in the U.S. on average. Though California residents use about half the energy of the average American household because of the state’s mild climate, it costs about the same percentage of family income to power a home in California as it does in most states in the Northeast, where chilly winters drive up energy use.

More regulation and higher costs are imminent. California municipalities, including Berkeley, Menlo Park, and San Jose, have nixed new natural-gas hookups, forcing construction of more-expensive-to-operate all-electric homes and commercial buildings. Towns in Silicon Valley, including Cupertino and Mountain View, homes of Apple and Facebook, respectively, have joined the bans. Big energy users have responded to the high rates and growing unreliability of the state’s electric system by locating new facilities elsewhere. Google has constructed giant server farms in Oregon. Intel, after complaining about the energy chaos that struck California in the early 2000s, built a $3 billion chip-production facility in Phoenix in 2008, and the firm recently broke ground on two new chip-manufacturing plants in Arizona—a $20 billion investment.

New York, already labeled by business executives as one of the worst states to operate in, is moving in California’s direction. Former governor Andrew Cuomo sacrificed thousands of energy jobs in economically struggling upstate communities when he banned fracking. Though New York’s electricity rates for industrial companies are already 50 percent higher than the national average, Cuomo also closed the massive Indian Point nuclear facility in Westchester, which generated about one-quarter of New York City’s energy, in favor of using unreliable renewable sources. He also refused to let energy firms build natural-gas pipelines to expand supply to the state. That prompted Con Edison, a downstate utility, temporarily to halt natural-gas hookups in portions of its area in 2019 because it couldn’t assure adequate supplies—a situation that the Business Council of Westchester described, in testimony before the state Public Services Commission , as “a serious threat to the future development and the economic health not just of Westchester, but across the entire metropolitan area.”

Energy constraints have already harmed local economies. A moratorium on gas hookups in upstate New York prompted cancellation of a new medical facility in Lansing, which would have employed 100, and it stalled the opening of other new businesses there, creating a local economic crisis. Power-grid operators in the Northeast warn that without greater supply lines, New York soon could face rolling blackouts.

F acing an increasingly stark competitive divide among the states, the Biden administration now seems intent on trying to level the playing field. The stimulus bill, passed after it was obvious that state revenues were rebounding, contained unprecedented language prohibiting states from using any of the money “directly or indirectly” to cut taxes. Republican attorneys general in 21 states sued to invalidate that provision, arguing that Washington was seeking unconstitutional constraints on a power traditionally reserved for the states. In particular, the lawsuits claimed, the notion that states couldn’t indirectly use Biden dollars to fund cuts—in other words, couldn’t reduce taxes if they accepted federal stimulus money, even if they had a budget surplus generated by their own tax revenues—would have made virtually any tax-cutting impossible. A federal judge agreed and issued an injunction against the rule.

Similarly, the administration’s proposed Protecting the Right to Organize, or PRO Act, would eliminate the right-to-work provisions of the Taft-Hartley Act, a move that legal experts have called “the most significant change to United States labor law in decades.” The measure would end the right of employees to opt out of joining a union if their workplace is organized. It would also single-handedly deprive right-to-work states of one of the most significant characteristics that manufacturing firms look for in deciding where to situate their plants these days. The probable effect would not be to shift production to blue states but to drive it overseas instead.

Thirty-six governorships are up for grabs in November’s elections. In 2008, after Obama won his first term, Republicans resided in just 21 governor’s mansions. Republicans now hold 28 governorships, which is why the new battle for jobs among the states has heated up more quickly in this election cycle. Though there may be fewer competitive governors’ races this year than in 2010, thousands of legislative seats are also in contention. Even a few major Republican victories could supercharge the already-electric competitive environment among states.

Republicans know that they have a playbook that works. Democrats were reminded of that in last November’s elections. The stakes this November will be even higher.

Article is LOCKED by author/seeder

Article is LOCKED by author/seeder

Tags

Who is online

46 visitors

The red states are totally winning the economic debate with the blue ones. From tax rates to regulations, to energy issues, to how the China virus was dealt with, people are voting with their feet and u-hauls and moving from unfree blue states to free red ones and even to red areas within some of the larger blue states. Not to mention that the red states have more family friendly communities with a different pace of life, better k-12 schools, and great small town and exurban places where a single family home with some land, lots of parks for kids and families, just enough shopping and plenty of recreation available nearby.