'The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man' Review: Paul Newman's Verdict

By: Michael O'Donnell (WSJ)

A handful of natural gifts elevated Paul Newman's career above the ranks of the mere movie star. What first won him notice were his eyes. They brought the young actor his smoldering fame: cerulean, intense and steady, they dared you to look away while he filled the screen. In films like "The Long, Hot Summer" and "Cat on a Hot Tin Roof," both from 1958, Newman's baby blues launched him into the zeitgeist alongside Marlon Brando and James Dean as a matinee idol full of rebellion and edge.

Much later in his career, Newman's voice became an equally striking feature. Unlike the eyes, the voice had to be earned; it was no pretty boy's birthright. Decades of smoking, drinking and pain produced a rusty baritone that could narrate its way to the very soul of a man's regret. Newman's voice settled into its terminal register in the 1980s, in movies like "Absence of Malice" and "The Color of Money." His world-weary characters could still get the girl, but the right one had long since gotten away. By the end of his career, Newman spoke with a lovely white-haired softness as a sort of national grandfather, teaching a boy to use a watch in "Nobody's Fool" (1994) and describing the rules of the road in Pixar's animated "Cars" (2006). Millions of children know him by his voice alone.

Newman (1925-2008) might have resented the notion that a pair of physical features bookended his career. He worked hard to get out from under his looks, and tried to maintain distance between his personal life and onscreen persona. But to the public, Paul Newman the commodity was an integrated, iconic whole. In a posthumous memoir, he writes that “what people were clamoring for was not me. It was characters invented by writers. It was the wit and ability” of others. Yet this sort of dissection can help explain a man weighed down by his own mythology.

“The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man” is all voice—which is to say, it is Newman at his best. It is based on five years of transcribed conversations between the screenwriter Stewart Stern, who died in 2015. The project had been abandoned by its co-creators in 1991, but was resuscitated after Newman’s death by his children. Interspersed into the narrative are reflections from directors, friends and family. The end product, compiled and edited by former Simon & Schuster publisher David Rosenthal, is twice the book one could have dared to hope for, a narrative that is astute, introspective and surprisingly graceful.

For a man so handsome and accomplished, Newman breathed in insecurity and exhaled doubt. He worried over his failings as an actor, husband and father. His 50-year marriage to Joanne Woodward—recently explored in Ethan Hawke’s lovely documentary series “The Last Movie Stars”—deserves our admiration. But Newman rues that it began with an infidelity that meant leaving his first wife and their three children. He describes his and Ms. Woodward’s ups and downs and their general volatility. Yet his summation reads like the mission statement for a romance well-lived: “Whatever it is, it’s wonderfully equal.”

Parenthood is the source of the most regrets. Of his own aloof father and possessive mother, Newman has bitter words. As a parent himself, he observes, “I was thought of as distant and reserved; well, that happened not because other people’s arms were too long but because mine were too short.” His son Scott, who died of an overdose in 1978, is the subject of anguished confusion. Newman describes failing to realize that the boy “might not want to be like me and ride in a race car or on a horse,” he writes. “I never did think to say to him: ‘Scott, would you like to go out on a horse? And it’s no big deal if you don’t want to do it.’ ”

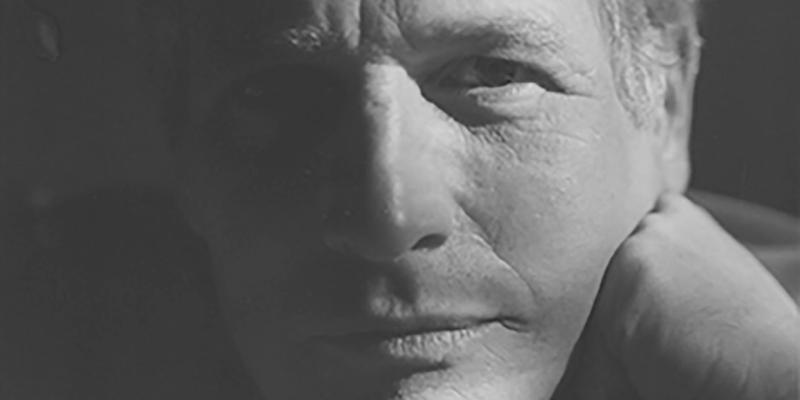

Paul Newman in 'Cool Hand Luke' (1967). PHOTO: ALAMY

Paul Newman in 'Cool Hand Luke' (1967). PHOTO: ALAMY One of the keenest observers in the book believes that Newman’s effort to master his insecurities produced a unique brilliance onscreen. “Paul is an exceedingly inhibited person, and painfully shy,” writes Stuart Rosenberg, who directed Newman in “Cool Hand Luke” (1967). “He fights all the time, fights all of his nervous qualities. But a strange thing happens when you fight like that and win. . . . What makes Paul so terribly interesting as an actor is there is always this desperation to win that battle.”

Desperation is the right word. Newman was at his best onscreen when playing hopeless cases, comeback kids or outright losers. He may not have performed a better scene than as a lawyer in “The Verdict” (1982) after learning that his star witness has abandoned him on the eve of trial. The crumpled look on his face is devastation personified. “The weak—the weak have got to have somebody to fight for them,” he tells his date in earlier in the movie. “Maybe,” he concludes, looking wistfully over the ruins of a futile life, “Maybe I can do something right.”

“Cool Hand Luke” anchored Newman’s second act and relied the power of another of his singular gifts: an explosive, infectious laugh. Here was Paul Newman as charisma bomb. Full of swagger and overflowing with bonhomie, he projected merriment even when facing down a bully or jumping off a cliff. “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” (1969) and “The Sting” (1973), both directed by George Roy Hill, completed the trio of iconic movies from this period. Both also co-starred Robert Redford, a golden god even better looking than Newman himself. The partnership helped him stop relying on his looks and lean into his chops.

A pair of witnesses testify in the book to Newman’s fundamental good nature during these years. Hill observes that “one of the great things about working with Paul is that, after a take, you can always say, ‘That’s terrible,’ to him. He’ll just shrug and laugh.” Newman’s friend Harold Willens writes about the actor’s delight surprising other drivers by gunning a Volkswagen that he had specially fitted with a Porsche engine. “That’s a lasting vision of him, this little boy having fun, roaring with laughter.”

Those were also the days in which Newman took his famed drinking to saturation levels. “I marvel that I survived them,” Newman admits. In “The Hustler” (1961), his pool prodigy blows his first chance to beat the great Minnesota Fats by drinking his edge away while Fats prepares for the next game. Life imitated art. Ms. Woodward observes in the book: “I used to think the only peace Paul ever found was that peace he used to find in being dead drunk. Now he finds it in racing cars.” As enduring an image onscreen as Newman’s smile is seeing him plunge his face into an ice bath to ease his hangover.

When we meet our heroes on the page, we want them to have something thoughtful to say—to make good on the admiration their outsize performances have won. Newman always seemed likely to pass that test, with his self-aware persona, storied marriage and generous charitable activities. Still, to see it come true in this rich book somehow imbues his characters’ pain and joy with fresh technicolor. He would have been the first to second-guess his own worthiness. “If I had to define ‘Newman’ in the dictionary,” he writes, “I’d say: ‘One who tries too hard.’ ” Yet even this constantly self-critical performer might have allowed that, with age, he began to learn the art of ease.