'Roald Dahl' Review: Giant Writer, Not Always Friendly

By: Meghan Cox Gurdon (WSJ)

In 'In Search of Lost time,'Marcel Proust warns of the futility of regretting one's past. "We are not provided with wisdom," he writes, "we must discover it for ourselves, after a journey through the wilderness which no one else can take for us."

By middle age, Roald Dahl (1916-1990) was thought by many who met him to be abrasive, arrogant and spiteful. He had carried out adulterous dalliances with married women and practiced other deceits. He had suffered pain and loss: the premature deaths of his father and a sister; brutal canings at British public school; a wartime crash-landing in the Libyan desert that left him temporarily blinded and disfigured. Dahl might have wished that his journey through the wilderness of life had been smoother.

Yet if Proust is to be believed, we can credit the hardships Dahl endured and his character flaws for fashioning him into the storyteller he became. Matthew Dennison’s biography, “Roald Dahl, Teller of the Unexpected,” makes it clear that without the unfortunate things that went into Roald Dahl, we might not have got out of him such delightful things for children as “James and the Giant Peach” (1961), “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” (1964), “The BFG” (1982) and “Matilda” (1988). Many of his books rank as modern classics. His oeuvre is widely loved in original book form and more widely known through adaptations for the stage, screen and radio.

Not every child adores Dahl, it must be said. The extremes of his fancy, the terrible persecutions of his protagonists and the yet more terrible fates of their persecutors can alarm and overwhelm. Not every adult likes him either. Dahl trafficked at times in racial, sexual and sectarian stereotypes, and his moral universe could be bleak. Mr. Dennison notes the dichotomy: “At its best, Roald’s writing both for children and adults is lyrical, hilarious, vivid, unpredictable, tender, and utterly absorbing; his darkest fictions portray without regret a world of cruelty, cynicism, misanthropy and caprice.”

Roald Dahl began life in Cardiff, Wales, the only son in a passel of daughters of wealthy Norwegian parents. His father, who had a romantic streak, named him after Roald Amundsen, the Norwegian explorer. His mother, regarded by her children as “practical and fearless,” enthralled young Roald with Scandinavian tales of witches, trolls and giants.

This maternal storytelling went into her son’s writing for children, as did his outrage at the perverse violence of adults in the schools he attended. In Dahl’s 1983 novel “The Witches,” a young English orphan learns at his Norwegian grandmother’s knee that secret societies of child-hating witches operate all over the world. Thanks to his grandmother, the boy is prepared when he discovers a witchy plot to transform the children of England into mice—so that their own parents will exterminate them.

In “The Witches,” as in all the best of Dahl, those who are brave and good ultimately triumph over wicked, greedy grotesques. Dahl’s baddies are indeed stupendously bad, but their power to affright in his books is tempered by Quentin Blake’s gloriously explosive ink-and-watercolor artwork. Blake’s pictures enrich all but one of Dahl’s 21 books for children and, Mr. Dennison notes, express “in a different idiom their combination of otherworldly mischief and spirited fantasy.”

Writer Jenny Uglow devotes a chapter to the men’s collaboration in “The Quentin Blake Book,” a handsome 90th-birthday celebration of Mr. Blake’s life and work. She relates a revealing story about the “The BFG,” which was already at the printers when Mr. Blake learned that Dahl was displeased. “Dahl was unhappy,” Ms. Uglow explains, “not with the illustrations, but because there weren’t enough of them.” Mr. Blake went back to the drawing board, Dahl went back the text, and between them they tweaked the story in image and word. They decided to eliminate the Big Friendly Giant’s leather apron because in the pictures it obstructed his movement, but they couldn’t come up with suitable footwear. Dahl declared his knee-length boots “dull.” Various ideas were tried without success, “until one day Quentin received a parcel in the post, containing a large, strange sandal; it was Norwegian and one of Dahl’s own. The BFG wore them straight away.”

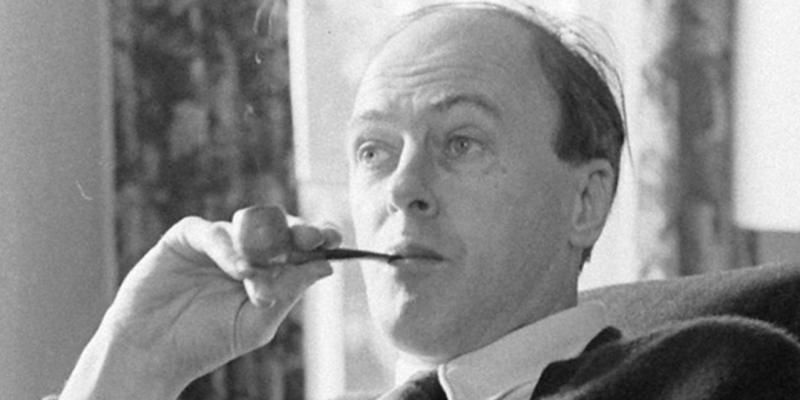

For all Dahl’s facility with language, he didn’t impress his teachers, and he didn’t go to university. Mr. Dennison relates that, after a sojourn in Newfoundland, the pipe-smoking, motorcycle-riding youth took a job in East Africa with Shell Petroleum, where he alternated between luxuriating in colonial comfort and motoring from farm to farm delivering fuel. With the advent of World War II, Dahl joined the Royal Air Force. On Sept. 19, 1940, the young pilot took off from an airstrip in Egypt. “Above the featureless sands he was swiftly adrift and, as the light thickened and the fuel gauge dipped, he became convinced he could not regain his course” and attempted a forced landing.

The plane smashed into the ground, and Dahl was badly mangled. A plastic surgeon had to reconstruct Dahl’s nose (using Rudolph Valentino as a model, Dahl claimed). After a long recuperation, Dahl rejoined his squadron and shot German planes out of the sky over Greece. In 1942, the RAF sent him to Washington to drum up support for the British war effort.

Dahl didn’t get on with people at the British Embassy, according to Mr. Dennison, but with his long-limbed good looks he made a splash in Washington society. As a habitué of the Georgetown scene, he played the swordsman with a series of wealthy and politically influential married women. (He complained that Clare Boothe Luce wore him out.) When Franklin Roosevelt invited Dahl to spend the weekend at Hyde Park, his country house, the Englishman recorded his observations in a 10-page memo for his colleagues at the embassy. In time he became an actual (if allied) spy, reporting on Americans to British intelligence.

It was while living in Washington that Dahl discovered his métier. The British adventure writer C.S. Forester was in town and asked Dahl to lunch. The young attaché struggled to describe his experiences in North Africa extemporaneously, so he sat down that night with pencil and paper to try again. “He wrote quickly,” we read. “At midnight, after five hours, the story was finished. Roald remembered its genesis as life-changing, akin to a mystical experience.” The amazed Forester passed the story straight to his agent, who sold it to the Saturday Evening Post.

Thus began Dahl’s career as a writer. His war stories brought him to the attention of Walt Disney, who dubbed the 6-foot-5 writer “Stalky” and hoped to make a film out of Dahl’s tale of pilot-tormenting gremlins dressed in suction boots and green bowler hats. The picture was never completed.

Over the next decade, Dahl moved between the U.S. and the U.K., chasing success. At this point in Mr. Dennison’s biography, the reader enters the kind of narrative purgatory that so often attends the life story of an aspiring creative type. There are the premonitory flashes of talent, a lucky break or two, and then a long period of sustained effort before the big famous thing happens. So it goes here. Dahl sells a story to the New Yorker. He adapts Somerset Maugham’s short stories for radio. He toils over two novels, neither any good.

In his personal life, things appeared happier. In 1953 Dahl married the American actress Patricia Neal, whom he’d met at a party organized by the playwright Lillian Hellman. It was not a joyous match, though it lasted three decades. Neither was in love with the other, and Dahl came to resent his wife’s wealth and fame. Soon the couple faced tragedy heaped on tragedy. In 1960 their infant son was nearly killed when a New York taxi hit his pram. In 1962 their 7-year-old daughter died of measles. In 1965 aneurysms ruptured in Patricia’s brain. She recovered eventually. The Dahls’ marriage never did. Roald embarked on an 11-year affair with a younger woman, Felicity “Liccy” Crosland, and in 1983 he divorced his wife to marry his mistress.

None of this makes for jolly reading, not least because Mr. Dennison’s pen does not always glide smoothly. At one point he discusses a dispute between Dahl, who had written the screenplay for Ian Fleming’s novel “Chitty Chitty Bang Bang,” and the film’s director, Ken Hughes. Dahl didn’t like the way Hughes had overhauled his script. Mr. Dennison writes: “If Hughes’s claims to authorship are correct, retrospective criticism of Roald on grounds of anti-Semitism in the characterization of the Child Catcher, the film’s villain who is not present in the novel—part of a wider criticism, which emerged later, of Roald’s anti-Semitism—appears unfounded.” It isn’t a fun sentence to read. It cannot have been a fun sentence to write. There’s regrettably little in “Roald Dahl, Teller of the Unexpected” to match the sprightliness and color that Mr. Dennison brought to “The Man in the Willows,” his 2019 biography of children’s author Kenneth Grahame.

The latter half of Dahl’s life proved cheerier and more orderly than the first, though he underwent many surgeries and was often in pain. Content with Liccy at Gypsy House, his home in England, he experienced what Mr. Dennison calls “creative and commercial apotheosis.” His books were selling like mad, and he was inundated with letters from enthusiastic young readers.

In the year he died, four of Dahl’s titles were the top bestsellers in British children’s fiction, and he was named the British Book Awards’ author of the year. Near the end, his biographer writes, Dahl became “less testy, more demonstrative, as serene as an immoderate nature that revelled in provocation could be.” His books, thank goodness, will never be serene.

Mrs. Gurdon, a Journal contributor, is the author of “The Enchanted Hour: The Miraculous Power of Reading Aloud in the Age of Distraction.”

I never knew his background. What a life it was! All I knew of him was that he wrote children's stories that had to have been far more interesting to children than just about all the kids books written before he came along.

The Book is:

Roald Dahl: Teller of the Unexpected: A Biography

By Matthew Dennison

Pegasus Books

272 pages