'Lives of the Wives' Review: Literary Spouses, Silent Partners

By: Heller McAlpin (WSJ)

When one of my undergraduate professors heard that I planned to attend a graduate writing program, he said, "I have one piece of advice for you." His counsel was not academic, but personal. "You're going to meet and fall in love with another writer. My advice is not to marry him. One writer in a family is bad enough."

I am reminded of his warning 46 years later—nearly 45 of them happily married to an architect—after reading "Lives of the Wives," Carmela Ciuraru's portraits of five 20th-century literary marriages, each awful in its own way.

Ms. Ciuraru, a critic who has edited two poetry anthologies and authored a book about pen names (“Nom de Plume”), sums up her attitude on the very first page: “The problem with being a wife is being a wife.” She continues: “In the marriages of celebrated literati throughout history, husband is to fame as wife is to footnote.” The literary wife’s role, Ms. Ciuraru explains, is to attend to “the outsize needs of the so-called Great Writer.”

Troubles arise when the wife, too, has artistic ambition and talent, triggering spousal resentment and jealousy that run both ways. This is especially true of the unions Ms. Ciararu considers, which span the years from 1914 to 1983. (A notable exception is the partnership of Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne, who fueled each other’s creativity.) But, Ms. Ciuraru wonders, “why does there exist, in many literary couples, an unspoken noncompete clause for the wives?”

“Lives of the Wives” owes much to Phyllis Rose’s eye-opening 1983 book, “Parallel Lives: Five Victorian Marriages,” which examined fluctuating power dynamics in a handful of prominent 19th-century couples. Like Ms. Rose, Ms. Ciuraru is intensely interested in the vicissitudes of relationships over time. But although she accepts Ms. Rose’s contention that unhappy marriages feature two narrative constructs which essentially present two conflicting versions of reality, her focus is mainly on the wife’s perspective.

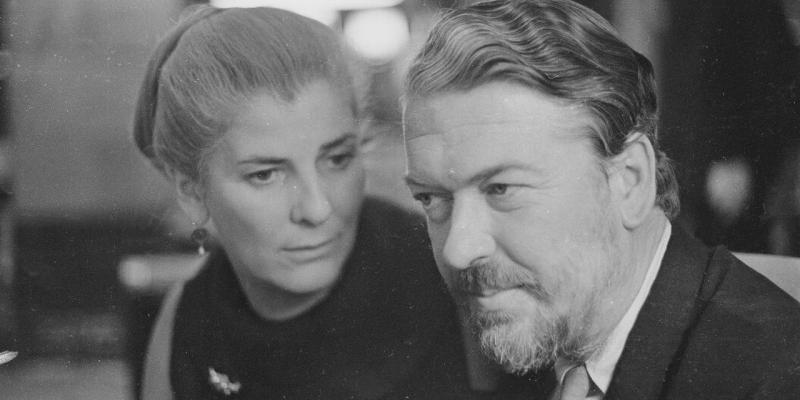

Refreshingly, Ms. Ciuraru has chosen to “steer clear of the all-star wifely roster”—Zelda Fitzgerald, Véra Nabokov, Nora Barnacle, Sofia Tolstoy, plus Hemingway’s four wives, Bellow’s five and Mailer’s six. Instead, she has handpicked five accomplished duos whose stories are less widely familiar, although all were considered power couples in their time: Una Troubridge and Radclyffe Hall, Elsa Morante and Alberto Moravia, Elaine Dundy and Kenneth Tynan, Elizabeth Jane Howard and Kingsley Amis, and Patricia Neal and Roald Dahl. Unusually for the time, these women, who all struggled to maintain their identity in marriage, kept their own names (though in Una Troubridge’s case, it was that of her first husband).

Ms. Ciuraru sketches cradle-to-grave portraits of each of her subjects, with a focus on their relationships—and the effects on the wife’s work—as they devolve from initial infatuation to bitter disillusionment. Although Ms. Ciuraru doesn’t draw explicit connections, there are striking similarities between her subjects. For starters, many endured difficult childhoods, often characterized by harsh parenting and early loss. Two of the men, Kenneth Tynan and Roald Dahl, were also scarred by their experiences of corporal punishment in boarding school.

Of the four women who had children, three—Una Troubridge, Elaine Dundy and Elizabeth Jane Howard—were less-than-ideal mothers. (Despite her busy acting career, Patricia Neal was devoted to her five children, as was their father, Roald Dahl.) Elizabeth Jane Howard was considered imperious by many and absentee by her daughter, but her stepson, Martin Amis, has credited her with shaping his life by turning him on to great literature. (“Turned out bloody well really!” Howard later said of Martin—long after she’d left hard-drinking Kingsley.)

Ironically, the most conventional and longest-lasting union, at nearly 30 years, was between the lesbian writers Radclyffe Hall and Una Troubridge. Hall, who liked to be called John, identified as male, and in current times might very well have transitioned. Una, born Margot Elena Gertrude Taylor in 1887, was a talented artist who, after her father’s death, abruptly married Ernest Troubridge, a widowed naval officer more than twice her age. He gave her a daughter—and syphilis. She hated her “wifely duties” and “found motherhood overwhelming.” When she met Hall in 1912, Una was instantly smitten and had few compunctions about displacing Hall’s longtime partner. Una happily gave up her artistic ambitions to serve “John” and manage her career; in fact, she supplied the titles for all of Radclyffe Hall’s books, including “The Well of Loneliness.” She was devastated when Hall, after falling for a young Russian gold-digger, predeceased her. Yet Troubridge managed to land on her feet and find happiness during her last 20 years.

The Italian novelists Elsa Morante and Alberto Moravia had a particularly miserable dynamic. Moravia—easy-going, prolific, and supportive of his wife’s work—was a font of successful novels and screenplays, including “The Conformist” (1947) and “Contempt” (1954). Morante, whose challenging novels about ordinary people living through times of crisis, including “House of Liars” (1948) and “History” (1974), have been hailed as an influence on Elena Ferrante, was the more difficult writer to live with and to read. Ms. Ciuraru writes about her pronounced nasty streak: “She seemed to derive pleasure and energy from altercations. She was trying to goad her avoidant husband to anger.” When he failed to react, his “incurable detachment” drove Morante into a rage.

New to me was Elaine Dundy, née Brimberg, who grew up wealthy in Manhattan but was traumatized by her father, a violent bully who set the stage for her turbulent marriage to the British theater critic Kenneth Tynan. His penchant for vicious takedowns unfortunately extended into his personal life—along with his flagellomania and masochism. Initially, the couple were madly in love and much in demand socially, but their already strained marriage took a turn for the worse after Dundy’s first novel, “The Dud Avocado,” was published in 1958 to great acclaim. When Tynan threatened divorce if she wrote another book, Dundy started “The Old Man and Me” immediately.

As Dundy’s story illustrates, “Lives of the Wives” is in part a “project of reclamation and reparation” driven by indignation over the subjugation of women’s talent. Amid the sometimes disheartening marital warfare, there are plenty of pleasant benefits in this deeply researched book, including enticing descriptions of forgotten literary gems. These include Elizabeth Jane Howard’s structurally innovative second novel, “The Long View”(1956), a dissection of a failed marriage told in reverse, and Dundy’s “The Dud Avocado,” about the Paris exploits of a young American who evokes Daisy Miller, Holly Golightly and Bridget Jones. Both novels are clever and still surprisingly fresh.

It should be noted that Ms. Ciuraru’s compulsively readable book examines these unions from a 21st-century vantage point, holding them up against the current ideal of marriage as an “egalitarian, sexually fulfilling, and mutual supportive alliance.” Her approach takes into account the recent exposure of high-profile cases of sexual abuse. She maintains, “We can no longer indulge or swat away misconduct because the offender crafts beautiful sentences. We must continue to interrogate the use of virtuosic literary achievement to justify monstrous behavior.”

A word of warning: Ms. Ciuraru’s dishy tales of marital misery might be better appreciated following a breakup than in anticipation of tying the knot. Not surprisingly, none of the wives she profiles remarried after these marriages ended, but several found contentment. As Ms. Ciuraru puts it, “For the wife, ‘happily ever after’ often means ‘happily ever after the divorce.’ ”