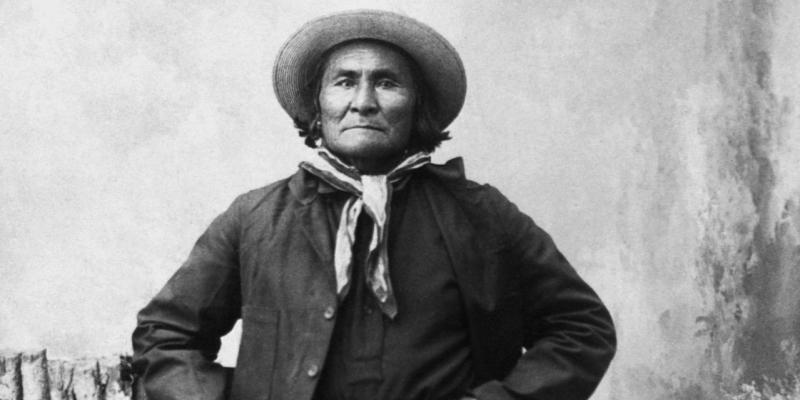

'The Last Campaign' Review: Battles of Sherman and Geronimo

By: Andrew R. Graybill (WSJ)

One of the enduring pleasures of "Heat," director Michael Mann's 1995 crime-noir thriller, is the opportunity to watch actors Robert De Niro and Al Pacino interact onscreen for the first time in their storied careers, if only in two—extended but pivotal—scenes. That, however, is considerably more overlap than between the protagonists featured in H.W. Brands's latest book, "The Last Campaign: Sherman, Geronimo and the War for America." Despite their twin billing, the general and the Apache leader do not cross paths in the book, and apparently never met. Moreover, while "Heat" remains original and taut (despite its nearly three-hour runtime), "The Last Campaign" is predictable and baggy, following an established path now beaten to dust by generations of professional and popular historians.

At first blush, author and subject seem well matched. Mr. Brands, who holds an endowed chair in history at the University of Texas-Austin, has published an astonishing array of volumes about the American past, ranging from the Revolutionary era to the late 20th century, and he has twice been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize (for his studies of Benjamin Franklin and Franklin Delano Roosevelt). He has also written several multicharacter biographies, including an exploration of the fraught relationship between Gen. Douglas MacArthur and President Harry Truman, and, more recently, a consideration of the different approaches to antislavery and abolition held by John Brown and Abraham Lincoln. Mr. Brands is a talented storyteller, with a novelist's feel for pacing and detail.

There are virtues to “The Last Campaign,” chief among them Mr. Brands’s linking of the histories of the South and the West, suggesting the ways that, in the words of a fellow scholar, “the Civil War bled into the Indian Wars.” After all, the reconstruction of the former Confederate states was only part of the federal government’s project of nation-building in the wake of crushing secession and ending slavery; incorporating the trans-Mississippi West was the other side of the same coin, which meant the subjugation of Native peoples from the Great Plains to the Pacific. Additionally, the strategy of total war that Sherman unleashed on Georgia and South Carolina in 1864—with its targeting of civilian as well as military populations—was imported to the postbellum West. Take, for instance, the Battle of the Washita in 1868, when Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer attacked a Cheyenne winter camp in western Oklahoma, killing as many as 150 people before burning the Indians’ provisions and slaughtering hundreds of their ponies, all in a bid to stymie the Natives’ ability to resist.

Alas, the weight of the book’s shortcomings keeps it earthbound. For one thing, Mr. Brands frames his story solely in terms of conflict, starting with the opening sentence, when he declares that “the war for America likely commenced early in the human history of the Americas,” from the moment humans crossed the Bering Strait into what is now Alaska. No doubt there was plenty of fighting across the millennia, as different groups struggled for control of territory and resources. But there were also extended periods of compromise and cultural exchange. None of this nuance, the stuff of human relationships outside the brutal confines of warfare, seems to interest Mr. Brands. For another, “The Last Campaign” is strictly narrative, a series of (often well-told) episodes rarely squeezed for their significance. To wit: Mr. Brands mentions some of the circumstances that exacerbated conflict between Natives and whites during much of the 19th century—above all the tendency of Euro-American colonizers to encroach on Indian lands, as well as the collapse of the bison herds on which Plains Indian societies depended—but rarely pauses to root these observations in context.

At times it seems as if Mr. Brands is almost allergic to analysis, a quality stemming in part from his habit of quoting the actors in his drama at excessive length. On the one hand, this permits readers to hear both sides in their own words, as when Gen. Ulysses S. Grant explains to a correspondent in 1867 that the war should be prosecuted “until all the Indians or all the whites . . . are exterminated,” or as Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce insists to treaty commissioners several years later, “the white man has no right to come here and take our country . . . we will defend this land as long as a drop of Indian blood warms the hearts of our men.” But too often Mr. Brands’s narrative is drowned by a tsunami of excerpted primary material, to such an extent that his own voice, as the expert, is all but imperceptible, leaving the audience to wonder what, if anything, is new or distinctive about his interpretation of this turbulent and tragic era.

But the biggest problems with “The Last Campaign” are structural and extend well beyond the misleading suggestion of the relationship between the main characters—or even the fact that one of them, Geronimo, disappears altogether for more than half the book. Mr. Brands devotes substantial attention to less familiar, and arguably less consequential, episodes such as the Modoc War along the California-Oregon border (1872-73) or the Second Battle of Adobe Walls in the Texas Panhandle (1874), while limiting his discussion of, say, the Sand Creek Massacre (1864) to just a few scant pages, when the butchery of Cheyenne and Arapaho people by Colorado volunteer soldiers led to a general Indian uprising on the Southern Plains. Likewise, though Apache resistance ended in 1886, most historians peg the conclusion of the Indian Wars to the slaughter at Wounded Knee Creek in South Dakota four years later, an event that earns but a sentence from Mr. Brands.

At the end of “Heat,” Robert De Niro’s character perishes in a shootout rather than return to prison. Geronimo made a different choice, surrendering to U.S. troops at Skeleton Canyon in Arizona and accepting confinement at a series of reservations: in Florida, Alabama and Oklahoma. He was never repatriated to the Southwest. Mr. Brands writes of this elegiacally, but acknowledges also that, even in detention, “the Indians retained a certain autonomy,” which permitted many of the tribes to maintain their language and culture in defiance of a system meant to turn them into what one historian has termed “brown white people.” In this sense, the war for America—as Mr. Brands appears to concede—looks more like a protracted stalemate than an unqualified triumph for Gen. Sherman and his colleagues.

Mr. Graybill is a professor of history and director of the William P. Clements Center for Southwest Studies at Southern Methodist University.

Tags

Who is online

538 visitors

The complaint seems to be that the history being told is very basic.

The Book is:

The Last Campaign: Sherman, Geronimo and the War for America

By H W Brands