'Shortchanged' Review: Technically Advanced

By: Jonathan Marks (WSJ)

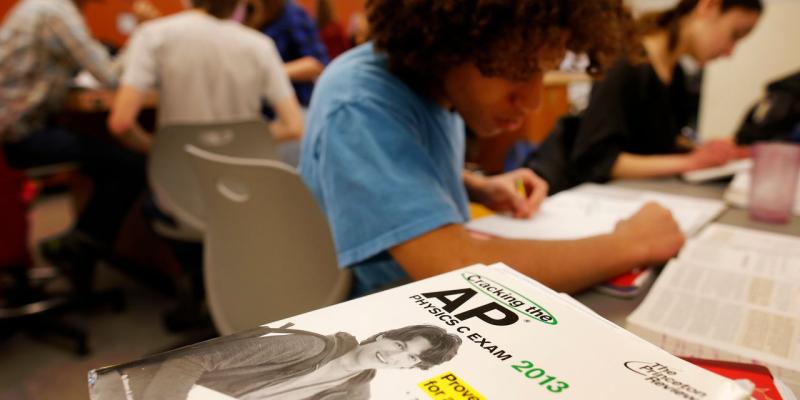

At a Valentine's Day news conference this year, Florida's Gov. Ron DeSantis floated a breakup with the College Board. The College Board, a nonprofit founded in 1900, dwarfs its competitors in the field of helping high-school students stuff their resumes and earn college credit. In 2022 it administered almost five million Advanced Placement (AP) tests in 38 subjects. Noting the board's outsize role in defining college-level work, Mr. DeSantis asked: "Who elected them?"

This was Mr. DeSantis talking, so progressives rallied around the board. But Annie Abrams, a high-school English teacher, suggests that even those on the left need not view the College Board as a friend. In "Shortchanged: How Advanced Placement Cheats Students," Ms. Abrams considers what the public gets from the AP program. Should we buy the board's line that educational equity demands the purchase of more $97exams? Ms. Abrams thinks not and believes that the promise of the AP program's "original vision" has been betrayed.

That vision, Ms. Abrams explains, was sponsored by the Ford Foundation in “response to concerns about the Korean War, Communism, and increased demands for a well-educated polity.” Under the influence of Robert Hutchins, the Ford Foundation’s associate director at the time and a former president of the University of Chicago, the foundation established in 1951 the Fund for the Advancement of Education. (After a pilot phase, the program was handed over to the College Board in 1955.)

The Ford Foundation was but one player in education reform. But it supported the two groups most responsible for giving intellectual shape to the AP program, the Blackmer and Chalmers committees, led, respectively, by Alan Blackmer, an English teacher at Phillips Academy Andover, and Gordon Chalmers, the president of Kenyon College. The two committees had their differences, but both posed the same question: What education suits the most capable students?

Education in the “liberal and humane tradition” was the answer given by James Conant, the president of Harvard University from 1933 to 1953 and an influence on the members of both committees. Such an education goes beyond good grounding in math, science and language to include “contact with both man’s emotional experience as an individual and his practical experience as a gregarious animal.” William Cornog, the president of Philadelphia’s Central High School and the executive director of the Chalmers Committee, argued that “poetry is more important to our salvation than rocketry.” The education that prepares students to lead the good life, an education that honors the “sanctity of the individual,” Cornog continued, is also the education that prepares them for democratic citizenship. It requires “inquiry and analysis” rather than submission to authority, and favors the contact of souls over rote learning.

The members of the Blackmer and Chalmers committees were, according to Ms. Abrams, overconfident in themselves and not confident enough in nonelite students. But they knew that the ability to benefit from a liberal education was, in Chalmers’s words, “distributed without reference to father’s occupation” and hoped that their program would raise standards for all students. In promoting what Conant called a “soulful, democratic, and multidimensional” education, they set a worthy goal.

Today’s AP program is far removed from that goal. To see this, one need only look at the College Board’s 300-page “AP U.S. History Course and Exam Description.” Compiled by high-school and college educators, it reads as if it were produced by bureaucrats and mad scientists. Here history education is divided and subdivided into six color-coded skills, 17 subskills, three “reasoning processes,” 11 reasoning subprocesses and eight themes, all of them spiraling through the course.

This dismal document reflects a technocratic tendency in the program that was there from the start. Conant, despite his praise of liberal education, we are told, “spoke about public education in technical, mechanized terms,” as a “vast engine” to be re-engineered. Frank Bowles, who led the College Board from 1948 to 1963, later admitted that the board tended to “subordinate the humane to the technical.” The Blackmer and Chalmers committees saw exams as necessary to award college credit for high-school courses but were wary of false claims to precision. If the “AP U.S. History Course and Exam Description” is any indication, that wariness has been overcome. The work of history, it implausibly implies, can be analyzed into discrete cognitive operations, which can be aligned with discrete historical skills to achieve discrete historical tasks. Ms. Abrams knows that good teachers get around poorly constructed frameworks. She laments that they have to subvert the AP program to pursue its original purpose.

Ms. Abrams hurts her case, however, by occasionally overstating it. The College Board influences instruction, but it is not a “totalitarian structure.” And her frustration at the “opacity of the organization’s financial relationships” leads her to at least one unworthy speculation. She notes that the Atlantic, which published an essay by the College Board’s CEO, David Coleman, is owned by the Emerson Collective, a for-profit “philanthrocapitalist” organization founded by Laurene Jobs. Ms. Abrams leaves it to her readers to conclude from this innuendo that the editorial process was rigged, a conclusion that insults the integrity of the magazine’s staff. The Atlantic, incidentally, recently published an essay that included some harsh words about the College Board. One of the co-authors was Ms. Abrams.

Such lapses notwithstanding, Ms. Abrams usefully shakes us out of our complacency about a program that seems good enough only because we expect so little of it. It isn’t the College Board’s fault that AP courses and exams are more a hurdle to clear in our brutal college-admissions competition than they are a spur to liberal education. But that competition doesn’t hurt the board’s revenue either. One doesn’t have to be a fan of Mr. DeSantis to think that we can do better.

Mr. Marks, a professor of politics at Ursinus College, isthe author of “Let’s Be Reasonable: A Conservative Case for Liberal Education.”

Who would have thought that American higher education would be in such a predicament.

The Book is:

Shortchanged: How Advanced Placement Cheats Students