Political Neutrality Is What Made American Newspapers Great

By: John Steele Gordon

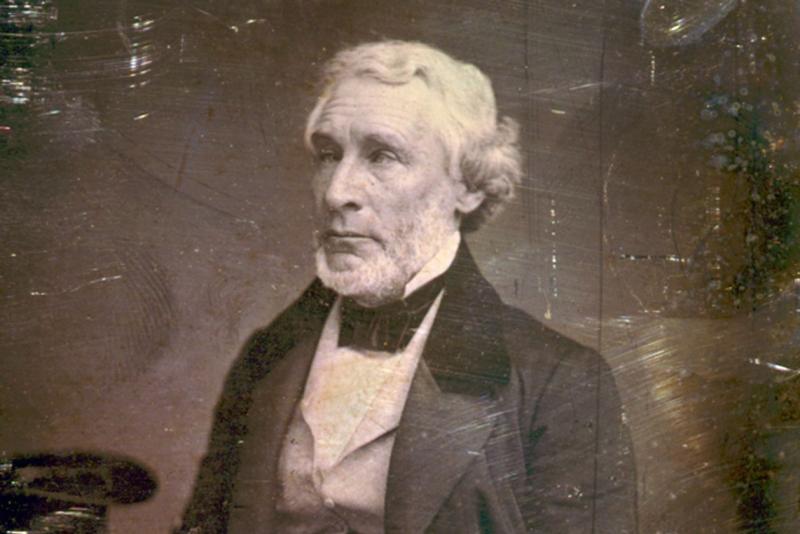

Many of America’s great newspapers have moved away from even the pretense of political neutrality. That tradition dates to 1835, when a Scottish immigrant named James Gordon Bennett founded the New York Herald. He had $500 in capital, an office in a dank cellar, and only himself as staff.

With a dozen other papers in the city, no one thought the Herald would amount to much. But by the time Bennett died in 1872, the Herald had the largest circulation in the world, its advertising revenue was second only to the Times of London, and his power to shape public opinion was immense, as was the fortune he had earned.

The Herald was something new under the journalistic sun. Newspapers had previously dealt either with narrow subjects, such as shipping or financial news, or were openly partisan, sometimes even subsidized by a political party.

Newspapers were also expensive. They usually cost 6 cents when an unskilled workman might expect to make 75 cents a day, so they were mostly read in taverns and coffee houses.

With the flatbed press, which had been in use since Gutenberg, only about 125 copies of a four-page paper could be printed in an hour. But by the early 1840s, when the steam engine was combined with the newly invented rotary press, 4,000 copies an hour became possible. The price of a newspaper soon dropped to a penny, and readership greatly increased.

Bennett was always on the lookout for new ideas. At the Charleston (S.C.) Courier, where he’d worked in the 1820s, he learned how the paper scooped the competition with news of the end of the War of 1812. The editors sent a boat out beyond the bar at Charleston Harbor to pick up the news from a passing ship. At the New York Enquirer, the editor admired Bennett’s talents but didn’t like his abrasive personality. Bennett offered to go to the nation’s capital and report from there, thus becoming the world’s first Washington correspondent.

He noted that Benjamin Day’s New York Sun—the most popular daily in the city, with a circulation of 15,000—was a general-interest newspaper, covering many subjects. But it also appealed to the lowest rung of literate society. The Sun was filled with gossip, lurid crimes and dubious tales of strange occurrences. It was much more like a modern supermarket tabloid than a newspaper.

Bennett anticipated the rising middle class that would dominate the Victorian Age. He wanted to move upmarket from the Sun and produce a mass newspaper that carried serious news about the real world for an upwardly mobile readership.

The Herald got off to a shaky start. Three months after the first issue appeared, Bennett’s printer was destroyed by a fire. But he hit his stride in 1836 thanks to one of the most famous murder cases of the 19th century. Ellen Jewett, a prostitute, had been murdered in her room at an upscale brothel. The madam quickly blamed Richard Robinson, who was young, wealthy and handsome, and whom Jewett had frequently entertained.

Respectable newspapers weren’t supposed to cover such scandalous material, but Bennett, with an unsurpassed nose for news, knew the story was irresistible, with its illicit sex, bloodshed, violence and wealth.

He gave all the details, visited the scene, observed the body, and interviewed the madam, the first time a witness interview—which quickly became a standard journalistic technique—appeared in a newspaper story. The Herald’s circulation skyrocketed, and the other respectable papers had no choice but to cover the story as well. At the height of the affair, the Herald was selling 15,000 copies a day, matching the Sun.

Bennett was responsible for an enormous number of journalistic innovations. The Herald was the first general-interest newspaper to include a weather report, provide sports coverage and include a daily stock table. It was the first to include an illustration in a story.

In a trip to Europe a few years later, Bennett signed up the world’s first foreign correspondents. He became the first journalist to interview a president who was still in office when he nabbed an exclusive with Martin Van Buren in 1839. He immediately exploited the telegraph and set up a pony express to get news of the Mexican War to the nearest city on the telegraph net. He even coined the word “leak” in the journalistic sense.

By the 1850s Bennett’s innovations had utterly transformed American journalism. The Herald had the largest circulation in the country. “No American journal at the present time can compare with it in the point of circulation, advertising, or influence,” admitted the thoroughly respectable Harper’s Weekly.

Newspapers had also become big business. Bennett had started with only $500. The New York Times , founded 16 years later, had needed $70,000 to get started. “The daily newspaper,” the North American Review wrote in 1866 , “is one of those things which are rooted in the necessities of modern civilization. . . . The newspaper is that which connects each individual with the general life of mankind.”

The penetration of newspapers into American life made public opinion a powerful force in politics for the first time. But much of the press’s power to influence public opinion came from what was, perhaps, Bennett’s greatest journalistic idea of all: He made the Herald politically neutral, printing opinion columns only on the editorial page. In his news pages he printed what he thought the readers would want to know, not what he wanted to tell them. Bennett realized that a newspaper that was the mouthpiece of one party would be read only by that party’s adherents. He wanted everyone to read the Herald.

Mr. Gordon is the author of “An Empire of Wealth.”