The End of Death

It was nearing the twentieth anniversary of my friend’s death, and it had been quite a few years since I’d visited his grave. I parked my car, and as I ducked through a gap in the hedge, I noticed preparations being made for a burial later in the day. But the grave I was looking for was near the fence that fronted the road. Heading in that direction, I stepped carefully along the neat cemetery lines.

Ignoring names in favor of dates, I could see from the grave markers that I was in the right general area. But the grave I sought wasn’t in this row. I worked my way along a row from which the creeping grass had not been trimmed. I had to go slowly in order to make out the names, but I didn’t expect that the grave I was seeking would be overgrown. But then, because I didn’t expect it, I was suddenly there. Just a small bit of the marker was visible through the encroaching grass.

Without thinking, I began ripping away the untidy strands. They seemed to fit with a grief, a sorrow, that was now two decades old. I hadn’t brought flowers, but I soon had a small bouquet of grass that I placed neatly beside the marker.

More than death

We all have these kinds of stories. They’re a profound part of what it means to be human. Every religion, philosophy, and culture has had to grapple with this somber human reality. Every grave we stand beside—whether it’s a gaping hole, a pile of fresh earth, or an obscured cemetery plot—challenges the core of what it means to be human and everything we believe about what life is or should be. And, of course, we all have those moments when we contemplate our own death and consider that at some point in the future we ourselves will no longer be part of our present lives.

Unsurprisingly, almost every religion, philosophy, and culture also brings with it a belief in some form of afterlife, the only significant exception being dogmatic forms of atheism.

In the religious sense, believers have often looked for the next life in the form of heaven, reincarnation, or some other story. In some formulations these realms have an influence on our physical and day-to-day world. In others life and death are quite separate. The Bible reminds us that God “has planted eternity in the human heart” (Ecclesiastes 3:11).* And a quick survey of religious and cultural beliefs supports this observation. Faced with the mysteries of death, human beings seem quick to fill the gaps.

Many of these beliefs have two practical results. First, there is often an element of reward or punishment in whatever comes after this life, giving meaning to the right and wrong things we do in this life. And second, these beliefs usually point to something better after death, easing the death process for the dying and the bereaved. We want to look forward to something good beyond death.

The last enemy

In spite of all of these beliefs, we still recoil from death. For a time we may be able to convince ourselves with the theory of a life well lived coming to a peaceful sunset, but we still miss our grandmother after she’s gone. Worse are the unexpected, violent, painful, and untimely deaths.

art of this difficulty is simply the mystery of death. For all our various beliefs and sciences, death remains the great unknown. But it’s even worse than that. In addition to being an insult to all we hold dear, work for, and value, death is an assault on our most basic human instincts. We want to live! Again, the Bible offers an honest summary of our predicament: “the last enemy to be destroyed is death” (1 Corinthians 15:26).

Freed from any pretensions about death being a natural part of life, we no longer have to feel guilty about our inability to come to terms with it. In the Bible’s worldview it’s appropriate to be horrified and heartbroken by death.

Death had no place in God’s original creation. We were created to live eternally, and nothing could be less natural than our lives coming to an end. In the Bible’s story, death and the sin that brought it are tragic aberrations. Indeed, we are right to resist death with all our mortal being.

A different, bigger hope

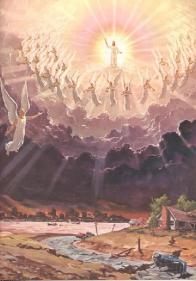

The Bible’s primary hope and promise is for the end of death itself. It isn’t just about each of us going “beyond,” hoping we’ll find something better “on the other side.” The Bible’s big story is about a new creation where “there will be no more death or sorrow or crying or pain. All these things are gone forever” (Revelation 21:4). The Bible points us to a much larger hope.

The Bible describes death as a sleep (Daniel 12:2; John 11:11–14). Like sleep, it’s temporary, and the next thing the sleeper will be aware of is an awakening—the resurrection. Compared to other beliefs and philosophies, there’s no time missed for the departed. Those who remain alive can be comforted that their friend or family member isn’t suffering, nor is he or she observing their sorrows on Earth.

Like many other traditions, the Bible talks about different outcomes after death for the good and the bad, the “righteous” and the “unrighteous.” John 5:29 tells us that there will be two resurrections—one for the righteous and one for the wicked. But the side you end up on is about more than merely doing right or wrong. It’s about choosing right or wrong. Did he choose to accept Jesus’ death on the cross for his sins? Did she choose to follow the principles of God’s law of love? Or did he choose to stick with sin and death?

God’s plan is to end death. That’s what Jesus taught, lived, and died for: “Everyone who believes in him will not perish but have eternal life” (John 3:16). In rising from the dead, He proved that death can be, and now is, defeated.

Our experiences of life are so familiar with death that it can be hard to imagine life without it. But when we reflect on the variety of hopes and beliefs about what happens after death, the biggest possible hope is that death itself will be no more.

And that’s what the Bible promises. Ultimately, “death and the grave [will be] thrown into the lake of fire” (Revelation 20:14). Led by the resurrected Jesus, the human race that chooses to be part of this death-defeating project will overcome and destroy death together in a glorious resurrection.

Back in the cemetery

I paused at my friend’s grave for just a few minutes, then, noticing others arriving, returned to my car. But walking away, I took a quick look back. Then as I started the car, a song began on my radio—“Shadows,” by the David Crowder Band: “Life is full of light and shadow. O the joy and O the sorrow. . . . When shadows fall on us, we will not fear. We will remember.” I remember the shock and challenge that my friend’s death was to me 20 years earlier, while I was still in school. There had been others, but they’d been more expected. This death was shocking, horrible. I still have questions and hurts about it, yet, “when all seems lost, when we’re thrown and we’re tossed, we remember the cost. We rest in Him, shadow of the cross.”

And 20 years later there’s still more to the story: death has been—and will be—defeated. And when it is, I hope and believe that our friendship will resume.

http://www.signstimes.com/?p=article&a=40050816129.786

Ignoring names in favor of dates, I could see from the grave markers that I was in the right general area. But the grave I sought wasn’t in this row. I worked my way along a row from which the creeping grass had not been trimmed. I had to go slowly in order to make out the names, but I didn’t expect that the grave I was seeking would be overgrown. But then, because I didn’t expect it, I was suddenly there. Just a small bit of the marker was visible through the encroaching grass.

Without thinking, I began ripping away the untidy strands. They seemed to fit with a grief, a sorrow, that was now two decades old. I hadn’t brought flowers, but I soon had a small bouquet of grass that I placed neatly beside the marker.

More than death

We all have these kinds of stories. They’re a profound part of what it means to be human. Every religion, philosophy, and culture has had to grapple with this somber human reality. Every grave we stand beside—whether it’s a gaping hole, a pile of fresh earth, or an obscured cemetery plot—challenges the core of what it means to be human and everything we believe about what life is or should be. And, of course, we all have those moments when we contemplate our own death and consider that at some point in the future we ourselves will no longer be part of our present lives.

Unsurprisingly, almost every religion, philosophy, and culture also brings with it a belief in some form of afterlife, the only significant exception being dogmatic forms of atheism.

In the religious sense, believers have often looked for the next life in the form of heaven, reincarnation, or some other story. In some formulations these realms have an influence on our physical and day-to-day world. In others life and death are quite separate. The Bible reminds us that God “has planted eternity in the human heart” (Ecclesiastes 3:11).* And a quick survey of religious and cultural beliefs supports this observation. Faced with the mysteries of death, human beings seem quick to fill the gaps.

Many of these beliefs have two practical results. First, there is often an element of reward or punishment in whatever comes after this life, giving meaning to the right and wrong things we do in this life. And second, these beliefs usually point to something better after death, easing the death process for the dying and the bereaved. We want to look forward to something good beyond death.

The last enemy

In spite of all of these beliefs, we still recoil from death. For a time we may be able to convince ourselves with the theory of a life well lived coming to a peaceful sunset, but we still miss our grandmother after she’s gone. Worse are the unexpected, violent, painful, and untimely deaths.

art of this difficulty is simply the mystery of death. For all our various beliefs and sciences, death remains the great unknown. But it’s even worse than that. In addition to being an insult to all we hold dear, work for, and value, death is an assault on our most basic human instincts. We want to live! Again, the Bible offers an honest summary of our predicament: “the last enemy to be destroyed is death” (1 Corinthians 15:26).

Freed from any pretensions about death being a natural part of life, we no longer have to feel guilty about our inability to come to terms with it. In the Bible’s worldview it’s appropriate to be horrified and heartbroken by death.

Death had no place in God’s original creation. We were created to live eternally, and nothing could be less natural than our lives coming to an end. In the Bible’s story, death and the sin that brought it are tragic aberrations. Indeed, we are right to resist death with all our mortal being.

A different, bigger hope

The Bible’s primary hope and promise is for the end of death itself. It isn’t just about each of us going “beyond,” hoping we’ll find something better “on the other side.” The Bible’s big story is about a new creation where “there will be no more death or sorrow or crying or pain. All these things are gone forever” (Revelation 21:4). The Bible points us to a much larger hope.

The Bible describes death as a sleep (Daniel 12:2; John 11:11–14). Like sleep, it’s temporary, and the next thing the sleeper will be aware of is an awakening—the resurrection. Compared to other beliefs and philosophies, there’s no time missed for the departed. Those who remain alive can be comforted that their friend or family member isn’t suffering, nor is he or she observing their sorrows on Earth.

Like many other traditions, the Bible talks about different outcomes after death for the good and the bad, the “righteous” and the “unrighteous.” John 5:29 tells us that there will be two resurrections—one for the righteous and one for the wicked. But the side you end up on is about more than merely doing right or wrong. It’s about choosing right or wrong. Did he choose to accept Jesus’ death on the cross for his sins? Did she choose to follow the principles of God’s law of love? Or did he choose to stick with sin and death?

God’s plan is to end death. That’s what Jesus taught, lived, and died for: “Everyone who believes in him will not perish but have eternal life” (John 3:16). In rising from the dead, He proved that death can be, and now is, defeated.

Our experiences of life are so familiar with death that it can be hard to imagine life without it. But when we reflect on the variety of hopes and beliefs about what happens after death, the biggest possible hope is that death itself will be no more.

And that’s what the Bible promises. Ultimately, “death and the grave [will be] thrown into the lake of fire” (Revelation 20:14). Led by the resurrected Jesus, the human race that chooses to be part of this death-defeating project will overcome and destroy death together in a glorious resurrection.

Back in the cemetery

I paused at my friend’s grave for just a few minutes, then, noticing others arriving, returned to my car. But walking away, I took a quick look back. Then as I started the car, a song began on my radio—“Shadows,” by the David Crowder Band: “Life is full of light and shadow. O the joy and O the sorrow. . . . When shadows fall on us, we will not fear. We will remember.” I remember the shock and challenge that my friend’s death was to me 20 years earlier, while I was still in school. There had been others, but they’d been more expected. This death was shocking, horrible. I still have questions and hurts about it, yet, “when all seems lost, when we’re thrown and we’re tossed, we remember the cost. We rest in Him, shadow of the cross.”

And 20 years later there’s still more to the story: death has been—and will be—defeated. And when it is, I hope and believe that our friendship will resume.

http://www.signstimes.com/?p=article&a=40050816129.786

Who is online

59 visitors