'I think I’ve written more Sherlock Holmes than even Conan Doyle': the ongoing fight to reimagine Holmes

By: Alison Flood

Arthur Conan Doyle’s master detective has been endlessly rewritten.

But nearly a century after the author’s death, how new writers portray him remains contested.

I've read all of Doyle, of course... and Laurie King and recently Enola, and Carole Nelson Douglas, and... so many that I have long since forgotten...

I liked best W. S. Baring-Gould's The Annotated Sherlock Holmes , with the whole canon re-written as a biography, including footnotes.

The first ever mention of Sherlock Holmes came in A Study in Scarlet , published in Beeton’s Christmas Annual of 1887. Dr Watson is looking for lodgings, and meets an old acquaintance who knows of someone he could share with, but does not recommend.

Young Stamford looked rather strangely at me over his wine-glass. ‘You don’t know Sherlock Holmes yet,’ he said; ‘perhaps you would not care for him as a constant companion.’

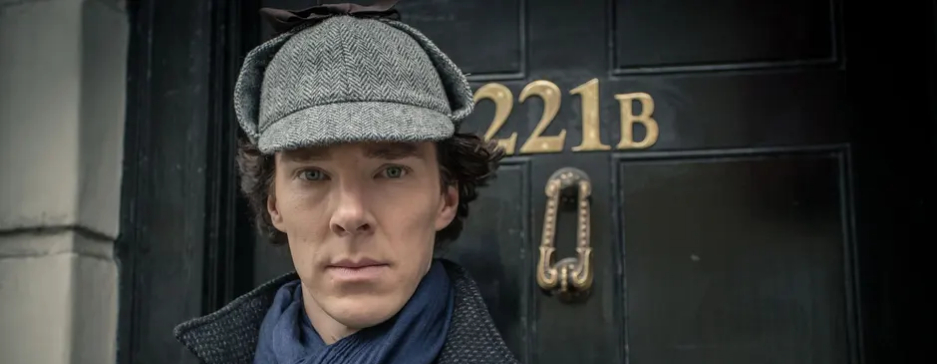

More than 130 years on, Holmes remains Watson’s, and our, almost constant companion. Arthur Conan Doyle’s detective landed a Guinness World Record for the most frequently portrayed human literary character in film and television in 2012, beaten only by the (non-human) Dracula. He remains enduringly popular on screen: when Benedict Cumberbatch plunged off the roof at the end of the second series of BBC1’s Sherlock, more than nine million viewers tuned in to find out what had happened to him . Last year, Netflix estimated that , in just four weeks, 76 million households watched Enola Holmes, starring Millie Bobby Brown as the sleuth’s little sister and Henry Cavill as Sherlock.

Alex Bailey/Netlfix/AP

And then there are the endless literary takes. There are Anthony Horowitz’s sequels, or Andrew Lane’s tales of a teenage Holmes. Star basketball player Kareem Abdul-Jabbar has written novels about Holmes’s older brother Mycroft; Nancy Springer wrote the Enola Holmes books, giving Holmes and Mycroft a younger sibling. James Lovegrove has combined the worlds of Holmes and HP Lovecraft in the Cthulhu Casebooks. Nicholas Meyer’s forthcoming The Return of the Pharaoh is drawn “from the Reminiscences of John H Watson, MD”, while Bonnie MacBird’s The Three Locks , a new Holmes adventure, is out in March.

“My step-grandmother, Dame Jean Conan Doyle, tried hard to stop the world doing what it liked with her father’s fictional characters. In the end she realised this was a fruitless exercise,” says Richard Pooley, director of the Conan Doyle estate and step- great-grandson of the author. “Instead she focused on giving her approval to those Holmes pastiches which were well-written and did not stray too far from Doyle’s characterisation. We have tried to do the same.”

The estate has authorised Horowitz’s sequels and Lane’s stories, but most Holmes adaptations come without the estate’s stamp of approval – not that that appears to put readers off. Pooley says that its approval comes down to the quality of the writing, and if the writer stays “true to Doyle’s depiction of Holmes’s and Watson’s characters” – meaning they don’t mind if Cumberbatch’s Holmes lives in modern London, or if Holmes and Watson are women, as in HBO Asia’s Miss Sherlock .

But not all spin-offs are equal in the eyes of Conan Doyle’s estate, and writers can run into quicksand when reimagining the beloved detective. “Putting the politest construction on it, they regard themselves as sort of custodians of the character and his world,” says Lovegrove, author of the Cthulhu Casebooks novels, which pit the detective against eldritch entities from the world of Lovecraft, and seven straight Holmes novels, most recently Sherlock Holmes and the Beast of the Stapletons.

One recent example was Netflix’s Enola Holmes. While most of Conan Doyle’s Holmes tales are in the public domain, the later stories, the last of which was published in 1927, remain under copyright in the US. When Enola Holmes was released last year, the estate argued that the film had infringed copyright by depicting a warmer and more emotional version of Holmes – traits the estate claimed were only revealed in the later stories. The case was eventually dismissed . The US copyright on the last Holmes stories will expire in 2023, after 95 years of copyright protection.

“They see themselves as keeping the flame alive and that’s why they’re doing these lawsuits,” says Lovegrove of the estate. “They’ve got these 10 stories and the things in those stories, like Watson’s second wife and his love of rugby, they’re saying these are still under their control.”

“This isn’t the first time the estate has put pressure on creators,” Klinger said at the time. “It is the first time anyone has stood up to them. In the past, many simply couldn’t afford to fight or to wait for approval, and have given in and paid off the estate for ‘permission’. I’m asking the court to put a permanent stop to this kind of bullying.”

Holmes and Watson, he argued, “belong to the world, not to some distant relatives of Arthur Conan Doyle”. The case went as far as the US supreme court, which concluded that the characters are in the public domain, with the exception of the final stories .

“The estate continues to try to squeeze the last few drops out of their lemons, I guess,” says Klinger, a leading Holmes expert. “Back then we thought they were behaving so outrageously that we were angered by it. We were totally unrealistic about what it was going to cost.”

He and King have continued to put out Holmes-inspired anthologies, most recently In League With Sherlock Holmes. “I think they’re over and done with us, I think they’re petrified by us at this point, it’s like whatever you do, don’t piss off Klinger and King,” says Klinger. He served as a technical adviser on Enola Holmes, and was involved in the Netflix lawsuit: “[The estate] had this whole ridiculous notion that Holmes was only emotional in the remaining copyright stories. Utter nonsense – emotions were widely on display in many other stories.”

King also writes the Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes series, about a 15-year-old who becomes the protege of Holmes, now retired. It isn’t only the estate that can prove thorny for those writers tackling such a hallowed character: when the first Mary Russell books were published in the 90s, she was “flamed” online by passionate Holmes aficionados.

“Ah, the bliss of ignorance! I think I was so focused on Russell, it never occurred to me that there would be people out there who felt protective about Holmes,” King says.But within a few years, Sherlockians understood her respect for Conan Doyle; King is now a card-carrying member of both the Baker Street Irregulars and the Sherlock Holmes Society of London.

“‘My’ Holmes begins in 1915, when Conan Doyle has finished with him,” she says. “But because these are not pastiches, I can let Holmes change and grow into the 20th century.”

One thing the authors and the estate can agree on is why Holmes has endured. “He is an archetypal figure: a human superhero, whose powers could be ours, who uses tools of science and observation available to us all,” says King. “We could be him, if only we were a little more clever, a little more dedicated. He throws himself against evil with all his strength and wits. And if we would rather he had a slightly more human face when he did so, that’s what Watson – or Mary Russell – is for.”

“Somewhere in the contrast, something wonderful happens,” agrees Lovegrove. “Holmes on his own would be absolutely unbearable. With Watson there to humanise him, he’s actually quite acceptable. You can’t have one without the other.” Like so many authors taking on Holmes, Lovegrove is a lifelong fan: “Every time I write Sherlock Holmes or Dr Watson, I get this little tingle in my stomach – that hasn’t really gone away. I think I’ve now written more Holmes, just in terms of words, than even Conan Doyle himself.”

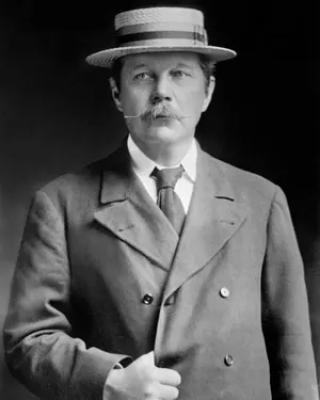

‘Tired of his money-spinning creation’ … Arthur Conan Doyle.

IanDagnall Computing/Alamy

Soon King, Lovegrove or whoever else so desires, will be able to mention Watson’s second wife, his love of rugby, and Holmes’s softer side. All of the remaining stories will be in the public domain in the US after 2022, 95 years after the final story was published. (Holmes’s UK copyright expired in 2000.)

Is Klinger planning an anthology featuring stories about Watson’s love of rugby, to celebrate? “I love the idea, if I can just find somebody who will write it – it won’t be me,” he laughs.

All the way back in 1881, Conan Doyle famously wrote to his mother: “I think of slaying Holmes … winding him up for good.” He would continue to tell his stories of the great detective for decades, but even Pooley believes his ancestor wasn’t that fussed over the last handful. “I believe he had grown so tired of his money-spinning creation that he put little effort into writing the final stories,” he says. “Doyle must have known anyway that Holmes had already taken on a life of his own and nothing he wrote about him would change the world’s view of Holmes as the brilliant, unemotional superhero.”

If you haven't read Laurie King's The Beekeeper's Apprentice... you should...