'American Catholic' Review: Doctrine and Democracy

By: Barton Swaim (WSJ)

In October of 2019, in an address to the de Nicola Center for Ethics and Culture at the University of Notre Dame, Attorney General William Barr defended the American tradition of religious freedom in forceful terms. "The imperative of protecting religious freedom was not just a nod in the direction of piety," he observed. "It reflects the Framers' belief that religion was indispensable to sustaining our free system of government." The attorney general went on, in his characteristically dry tone, to inveigh against attempts by American progressives to use the law to punish religious people for holding views that offend the latest liberal consensus.

Mr. Barr's identity as a Roman Catholic was barely remarked upon in the commentary after the speech, but that small fact was—from an historical viewpoint anyway—one of the most interesting things about it. For a millennium or more the Roman church viewed itself, and in many ways still views itself, as an institutional check on societal excesses and governmental abuses. The duty of political rulers was not to foster "religion" in general, or to ensure that "religious viewpoints" held a place in the "public square," as Mr. Barr put it in his address. Their duty, in the Roman Catholic view, was to guard the truth and combat error—"error" meaning heresy.

Sixty years ago, the older understanding of Rome's proper role in the world still prevailed sufficiently to make voters suspicious of a presidential candidate who belonged to the Roman Catholic Church. "I do not speak for my church on public matters," John Kennedy told the Greater Houston Ministerial Association in 1960, "and the church does not speak for me." The charge that a Roman Catholic president would feel obliged to follow dictates from the Vatican on matters of public policy had been made as well against the first Catholic presidential nominee, Al Smith, in the 1928 election—this despite the fact that Smith knew little about Catholic social teaching. "What the hell is an encyclical?" he once asked.

The sort of anti-Catholic animus that forced Smith and Kennedy to insist on their independence from Rome isn't quite a thing of the past, but nowadays it's employed for exclusively partisan ends (think of Sen. Dianne Feinstein's weird assertion to Amy Coney Barrett that "the dogma lives loudly within you"). That Joe Biden's Catholicism was hardly mentioned during the 2020 presidential campaign is a measure (a) of how little both voters and politicians care about confessional religion in the 21st century, but also (b) of how much Catholic doctrine on church-state relations and liberal democracy has changed since the middle of the last century.

The transformation of Catholic political thought, both within the church hierarchy and among Catholic intellectuals in the United States, is the story of D.G. Hart's "American Catholic: The Politics of Faith During the Cold War." Mr. Hart, who teaches history at Hillsdale College, writes perceptively and with a cold analytical eye; his narrative is free of ax-grinding and point-scoring. "American Catholic" is intellectual history of an excellent sort.

The anti-Catholic bigotry of midcentury WASP critics like Paul Blanshard, author of "American Freedom and Catholic Power" (1949), was ugly and narrow-minded but not, Mr. Hart rightly notes, completely irrational. In his "Syllabus of Errors" Pope Pius IX anathematized many components of modern liberal politics as heretical—separation of church and state, for example—and in 1899 Pope Leo XIII condemned, among other things, freedom of the press ("the assumed right to hold whatever opinions one pleases upon any subject and to set them forth in print to the world").

Leo termed liberal democratic conventions "Americanism." By the time of JFK, Mr. Hart writes, Americanism was "a low-level heresy that had hung over American bishops and priests since the 1890s." The key figure in the work of reconciling Americanism with official Catholic teaching—Mr. Barr alludes to him in the abovementioned speech—was John Courtney Murray (1904-67), a Jesuit priest who taught theology at a Maryland seminary. Murray believed that, at a time when atheistic totalitarian regimes were on the rise around the globe, the Church had a duty to affirm the ideals of political freedom and religious pluralism. In the mid-1950s Murray was told by Church authorities to refrain from publishing in official Catholic journals, but in 1960 he brought out the collection of essays for which he is best remembered, "We Hold These Truths: Catholic Reflections on the American Proposition."

The question for Murray and other American Catholic intellectuals, Mr. Hart writes, "was how a church that had opposed most modern politics could approve the very liberties that had once seemed so antithetical to Christendom's social order and the papacy's central place in it." The answer came through a complex and sometimes convoluted debate among theologians, politically conservative journalists, popes, Church councils and Catholic politicians.

Murray won the debate in important respects. In December of 1965 the Second Vatican Council passed the "Declaration on Religious Freedom," and subsequent popes, especially John Paul II, repeated the Church's condemnation of communism and—implicitly at least—embraced democracy, pluralism and free markets. But of course a host of questions would remain unsettled, chief among them the place of socialism in Catholic teaching. In 1961 Pope John XXIII promulgated the encyclical "Mater et Magistra" (Mother and Teacher), in which the pope seemed to endorse statist economic policies at the expense of policies broadly known as capitalism. That prompted William F. Buckley, Catholic editor of the conservative political magazine National Review, to publish a scathing editorial in which the magazine called the encyclical "a venture in triviality." A later issue quipped, "Mater, si, Magistra, no." Catholics on the political left jumped to the pope's defense. So began, or rather continued, a long and complex debate involving, inter alia, conservative Catholics who reject Church teaching on economic policy, progressive Catholics who reject Church teaching on social policy, and traditionalists who accept, or at least try to accept, both.

That debate rages on, with the current pope appearing to welcome a new and extreme form of social Americanism even as he abandons the principles championed by John Courtney Murray. Meanwhile secularism continues its long march through Europe and the Americas.

In an earlier book, "The Lost Soul of American Protestantism" (2002), Mr. Hart contended that both liberal mainline and evangelical churches in America lost their cultural and political "relevance"—a vogue term from the '60s to the '90s—precisely by seeking it so diligently. I wonder if I'm right to read "American Catholic" through the lens of that earlier book. Has the Church of Rome committed a similar error? The spectacle of Pope Francis endorsing disgraced economic theories and suggesting the Church approve same-sex civil unions long after developed nations have embraced full-on marriage for same-sex couples is enough to make one question the whole premise that religious bodies have any special wisdom in the sphere of politics.

"Catholicism is the majority religion of Italy, Spain, and nearly all Latin American countries. In 2001, about 24 percent of Americans identified themselves as Catholic, making Catholicism the largest Christian denomination in America (if the Protestant denominations are counted individually). "

.

I think it is fair to say that the Catholic Church's influence among the faithful is waning and it's influence politically is almost at zero. The above mentioned Latin American Catholics maybe being the exception. The current Pope being the most political, yet least influential.

Just one man's (Catholic's) opinion.

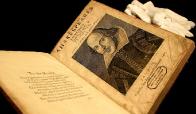

The book is:

AMERICAN CATHOLIC

By D.G. Hart

Cornell, 261 pages

Islam, however, continues to consume a higher percentage of the world's religious. Isn't that just peachy?

I'm not much of a fisherman, but I have a feeling that there's a lot of chum in the water.

I didn't bother raising the Constitutional concerns of AG Barr in places like Nevada which continues to restrict in-person worship services while moving to a phased reopening of shuttered businesses.

You see AG Barr with be cleaning his desk out in a matter of months and I don't think anybody will be concerned with religious liberties after that.