'Poverty, by America' Review: Poverty Is Your Fault

By: Leslie Lenkowsky (WSJ)

In his State of the Union address in 1964, President Lyndon Johnson famously called for "an unconditional war on poverty." Since then, according to the Census Bureau, the proportion of Americans with incomes below the official poverty threshold has fallen from 19% to 11.6% (in 2021). Using a broader measure of income, one that includes social-welfare benefits such as food stamps and housing subsidies, the share is lower still: 7.8%.

To Matthew Desmond, these results, as impressive as they might seem to be, are not even close to good enough. In "Poverty, by America," he begins by asking why there is "so much poverty in the United States." He then proceeds to describe, in sometimes harrowing detail, the hardships of American poverty and to advance his own explanation for poverty's persistence.

For Mr. Desmond, a sociology professor at Princeton and the author of “Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City” (2016), poverty persists not because of the personal failings of the poor or even because of the insufficiency of government social programs. Rather, the blame rests on the entire society—that is to say, on those of us who are not poor. There are too many poor people in the U.S. today, Mr. Desmond argues, citing Tolstoy, because too many aspects of American life “make them poor.”

Mr. Desmond’s culprits are mostly familiar. Large corporations, like Amazon or Walmart, pay their employees too little and resist unionization that might improve working conditions. Banks are inhospitable to the poor, making saving and obtaining credit more difficult than it should be and driving the poor to use “payday loan” shops that charge exorbitant interest rates. Zoning laws restrict the availability of “affordable housing” and make the amenities that come with livable neighborhoods—good schools, accessible health care, safe streets—less possible or likely.

Consumers, for their part, don’t give enough priority to shopping at stores that treat their employees fairly or that support progressive policies. “My family,” Mr. Desmond writes, “stopped shopping at Home Depot after learning about the company’s hefty donations to Republican lawmakers who refused to certify the results of the 2020 presidential election.”

Not surprisingly, Mr. Desmond is all in favor of raising taxes on the wealthy to pay for increased assistance to the poor. But his criticisms of existing social programs are not quite so predictable. While ultimately endorsing an increased minimum wage, Mr. Desmond acknowledges—though he doesn’t accept—research showing that raising the minimum wage can be harmful to workers, by reducing the number of jobs. He views programs that aid low-income workers, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit and the child tax credit, as essentially subsidies to employers, allowing them to pay low wages. Though he recognizes that the U.S. is now spending much more on poverty than it used to, he says that the spending isn’t having the effect it should “because the American welfare state is a leaky bucket.” Much of the money, he says, goes to people who are not poor, including lawyers who sue the government for benefits.

What is needed most of all, in Mr. Desmond’s view, is a shift in perspective or a change of consciousness. We all need to become “poverty abolitionists,” he writes, “unwinding ourselves from our neighbors’ deprivation and refusing to live as unwitting enemies of the poor.” He isn’t calling for us to follow Tolstoy and take vows of poverty; he even says that he’s not calling for more income redistribution, since America already manages to do a fair amount of it, though in the wrong direction—toward the better-off, not the needy. He argues instead that, by changing how we shop, reside, invest, donate and spend public funds—by redefining the norms that guide our lives—we can help the poor enjoy the kinds of choices that other Americans have today.

For Mr. Desmond, in fact, poverty is less a matter of insufficient income than insufficient options. The poor, in his portrait, are basically compelled to work in low-paying jobs, live in rundown communities and make use of high-cost banks. It’s almost as if they aren’t allowed to do otherwise. Yet in his discussion of the ways in which the poor might be empowered, he overlooks school vouchers, which enable low-income families to bypass neighborhood public schools if they wish. He also gives short shrift to similar programs—aimed at helping the poor—in housing and health care, such as the Affordable Care Act, which was meant to aid the uninsured but which, he tells us without explaining why, has left 30 million Americans uncovered a decade after its enactment.

Nor does Mr. Desmond consider whether the poor might sometimes prefer to stay in their “segregated” neighborhoods (as he calls them) rather than move next door to people with whom they have little in common, as he thinks they should be encouraged to do. As for turning companies like Amazon or Walmart into union shops, he doesn’t say how doing so would create more job opportunities rather than limit them to those who hold a union card.

Since it is meant to be a call to action more than a plan for achieving it, “Poverty, by America” doesn’t dwell on problems like this or on the feasibility of other proposals. Mr. Desmond believes that we still live in the world that John Kenneth Galbraith characterized, in 1958, as “private affluence amid public squalor.” The resources for eliminating poverty are bountiful, Mr. Desmond maintains, and need only to be put to better use. Gone are the messy complications of politics and economics or the actions of the poor themselves: The high rates of school failure or drug use in poor communities, for instance, barely warrant attention. In Mr. Desmond’s view, we have “so much poverty” because we lack the will to have less of it. If only that were so.

A better title would have been "Marxism at Princeton."

So much for the idea that life should be devoid of consequences for poor decisions.

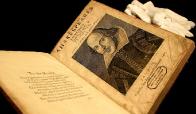

For those interested the book is:

Poverty, by America

By Matthew Desmond

Crown

Nothing that the author Desmond says is untrue. But, a lot of people, certainly the majority, dont want to hear it. It reminds me a little of the white response to black history - you're correct but so what?

Capitalism REQUIRES poverty. Without poverty there could be no "race to the bottom" for wages. Even with all the government spending on social programs, poverty in America has never gone below 10%. And it never will. Without the social programs the poverty level would be 16 or 17 percent, or higher, which is what it was prior to the "Great Society". The idea that everyone can pull themselves out of poverty by their bootstraps is nonsense. "Anyone" can, but not "everyone". Poor people make the system that makes people rich possible. As a society we should be willing to help them as much as possible.

Typical.

"Why take a hand up, when it is far easier to take a hand out"

The perfect leftist mantra.

Let's say the haves provide half of what they have to the have-nots. Then the haves will still have and have-nots will become the have-somethings.

So... a professor in his ivory tower is eager to spend other people's money and direct other people's activities to affect a theoretical "solution" that completely ignores reality.

He'll now earn book royalties and speaking fees to go around validating the feelings of limousine liberals.

I wonder how he intends to spend the money.