The Enigma of Robert E. Lee

By: By MACKUBIN THOMAS OWENS

O f all the American icons that have been pushed off their pedestals lately, none has fallen farther and harder than Robert E. Lee. Over the years, Lee was admired by even those who certainly had no sympathy for the cause for which he fought. Long viewed as an exemplar of soldierly virtue, integrity, magnanimity, and humanity, Lee has recently come under relentless attack and his alleged virtues have been called into question.

He was once regarded as not only a regional but even a national hero, a Christian gentleman as well as a magnificent commander who eventually succumbed only to an army with superior resources. Now we are treated to essays such as “The Myth of the Kindly Robert E. Lee,” accusing him of being a racist slave-beater, as well as to denunciations by Army officers such as David Petraeus who, having once lauded him, now dismiss him as a traitor.

Fortunately, Lee is the subject of a new biography by the prolific Allen C. Guelzo, one of our most accomplished Civil War historians and a foremost Lincoln scholar. Guelzo, the senior research scholar at the Council of the Humanities and the director of the Initiative on Politics and Statesmanship in Princeton’s James Madison Program, is the first three-time winner of the Lincoln Prize, for, among other works, his Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America (2005), which remains the definitive treatment of that document.

As a staunch Lincoln man, Guelzo might be expected to join in the Lee-bashing. But that is not his style. He has instead provided a fair treatment, placing Lee’s remarkable life in its proper context. He praises what should be praised and criticizes what should be criticized.

Guelzo seeks to address the “mystery” of Robert E. Lee: How did a man whose character, dignity, rectitude, and composure created a sense of awe in most of those who observed him also exhibit characteristics such as insecurity, petulance, impatience, contempt, and, on at least one occasion, violent anger? Also, how did a man of honor commit the crime of treason?

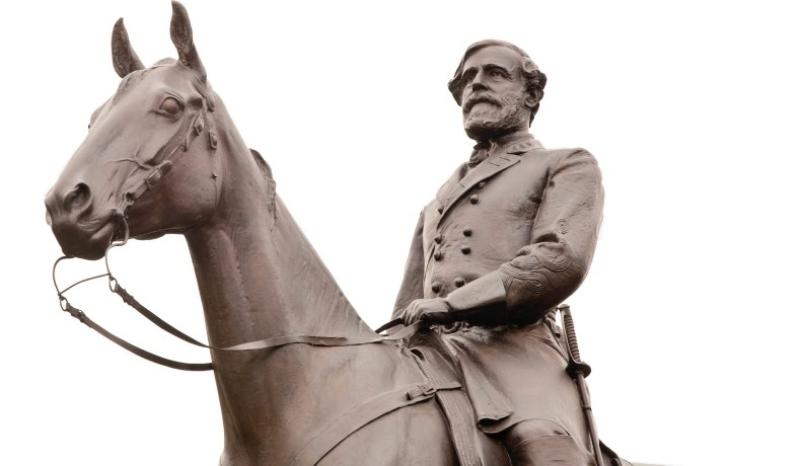

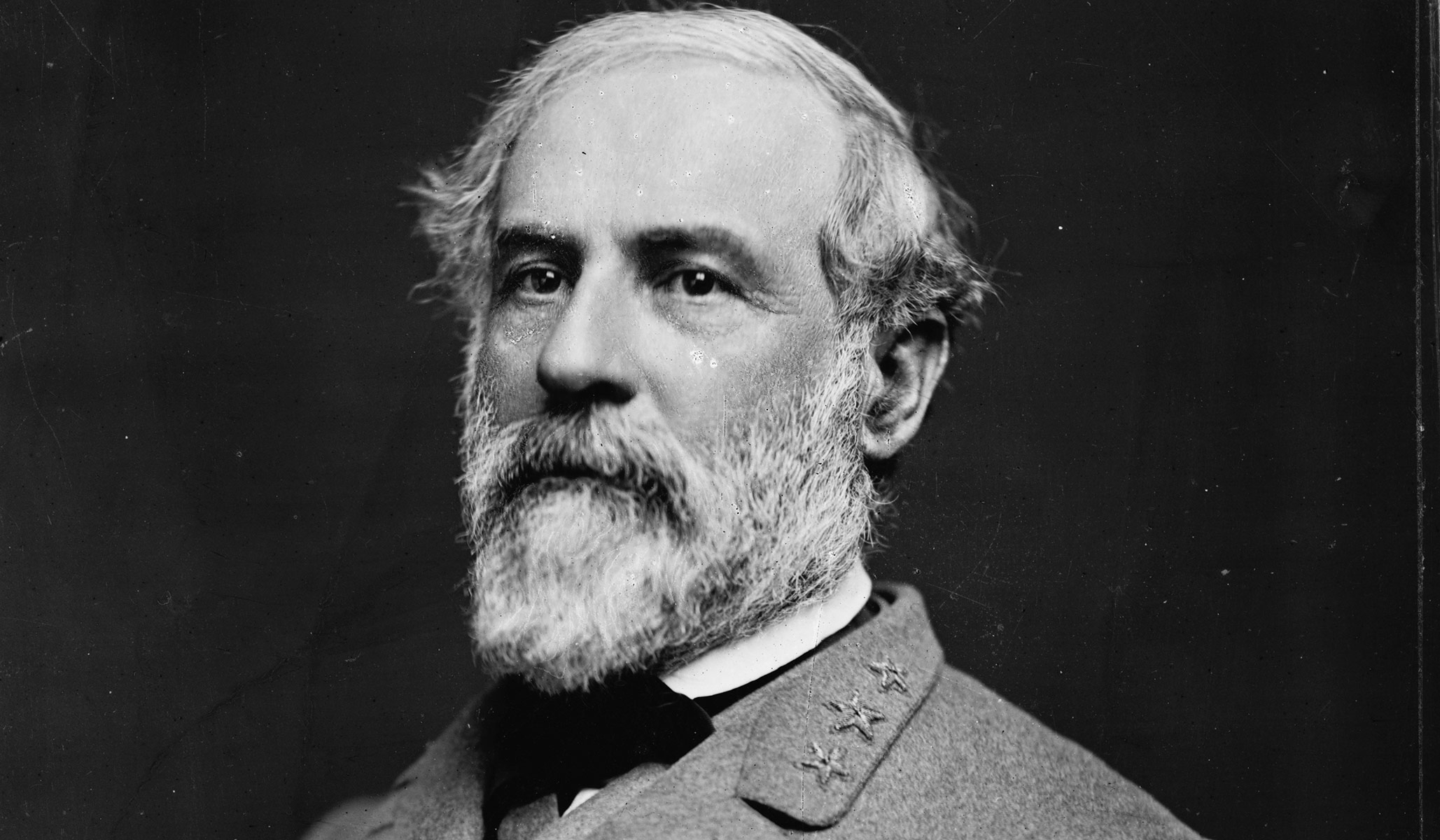

General Robert E. Lee, March 1864.

Library of Congress

As Guelzo notes, since the publication of Thomas Connelly’s critique of Lee as a “marble man,” critics of Lee have argued that the reality is at odds with the image created by his admirers. But by treating the image of Lee as simply false, they have missed the man’s complexity. Guelzo contends that “casting Lee in contradiction — as either saint or sinner, as either simple or pathological — is, in the end, less profitable than seeing his anxieties as a counterpoint to his dignity, his impatience and his temper as the match to his composure.”

The key to unlocking the mystery of Lee is to understand three factors that shaped his personality: his pursuit of “redemptive perfection,” his yearning for independence, and his quest for security. Guelzo contends that all of these arose from the trauma of his father’s abandonment of the family when Robert was only six years old. His father, Henry Lee, was a hero of the Revolution and one of Washington’s favorite officers.

“Light Horse Harry” Lee served as governor of Virginia, but his ardent Federalism alienated the Jeffersonians who dominated Virginia politics. It wasn’t politics, however, that did him in; it was a series of financial scandals after the war. Indeed, he sought to ensnare Washington in one of his investment schemes. After a stint in debtors’ prison, he decamped for the West Indies. Guelzo, like others before him, believes that Lee’s famous rectitude was an attempt to atone for Harry’s sins, to “perfect the imperfections that Light Horse Harry had visited on the family.”

Throughout his life, Lee’s pursuit of redemptive perfection shaped his character. This pursuit, and the tensions that it created, is a dominant theme of Guelzo’s biography. Lee was pulled between his duty to his family on the one hand and the demands of Army service on the other. After he married the daughter of Washington’s adopted son, George Washington Parke Custis, both she and his father-in-law pressured him to leave the Army and assume responsibility for Arlington, the Custis home overlooking the Potomac. As it was, Lee was forced to carve out an inordinate amount of time from his U.S. Army duties to attend to the affairs of his father-in-law, whose fecklessness regarding the management of money was a constant problem for Lee.

Given the recent charges against Lee, the most important parts of the book are Guelzo’s discussions of Lee and slavery, especially his relationship to the slaves at Arlington, his decision to follow Virginia out of the Union, and the charge of treason.

Lee has often been described as an opponent of slavery, but Guelzo shows that his views mirrored those of many other Southern whites: Slavery was particularly regrettable as a burden on whites rather than as an injustice to blacks. He recognized the evils of slavery but concluded that there was little that could be done to dismantle the institution.

His dislike of the institution was exacerbated by his efforts to execute his father-in-law’s will, which manumitted his father-in-law’s slaves. Because of legal issues arising from that will, Lee was unable to free them before January 1, 1863, the day that Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation took effect.Although he accepted the outcome of the war, he continued to believe that blacks were incapable of self-government. He opposed granting the franchise to the freedmen and came to criticize democracy itself. He was certainly no advocate of black equality, as some have suggested.

Did Lee commit treason? According to its definition in the Constitution, the answer would seem to be yes. Guelzo agrees, but he also provides facts that might absolve Lee. Although Guelzo is critical of Lee’s decision to turn against the Union, he makes it clear why Lee did. Lee may have served in a nationalizing institution, the U.S. Army, but he was also bound to his state by virtue of his old Virginia family.

For Lee, as for many others at the time, the United States as a unified entity was at best an abstraction. The patriot’s true loyalty was to one’s place: where one was born, where the family hearth was to be found. For Lee, that was Virginia.

The issue for Lee and others who followed their states out of the Union was its dual nature. As James Madison observed in Federalist No. 39, “the proposed Constitution . . . is, in strictness, neither a national nor a federal Constitution, but a composition of both.” At a time when the states have become little more than administrative units and tax collectors for the national government, it is hard for us to realize the degree of sovereignty that was reserved to the states before the Civil War. For instance, John Brown was convicted and executed for the crime of treason against not the United States but Virginia.

The wording of the oath that Lee took also suggests that the officer’s loyalty was to the United States not in a singular but in a collective sense: “I . . . do solemnly swear or affirm (as the case may be) to bear true allegiance to the United States of America, and to faithfully serve them honestly and faithfully, against all their enemies or opposers whatever” (emphasis added). One could infer, and many did, that loyalty to one’s state was at least equal to one’s loyalty to the national government, if not paramount. Because of this ambiguity, the oath was changed in 1862.

What of Lee’s military prowess? Although some military historians, such as the British writer J. F. C. Fuller in the 1930s and more recently Connelly and Alan Nolan, have criticized his generalship, his martial reputation has remained fairly high. Guelzo concurs, observing that Lee managed Confederate military affairs with “extraordinary skill.”

Lee has been both the beneficiary of the “Lost Cause” school of Civil War historiography and its victim. Clearly his elevation to the status of a nationally honored secular saint owes much to the triumph of that school for a century after the war. But as the school came under attack, so did Lee’s reputation. There are two components of the Lost Cause school. The political component — the notion that the cause of the war was not slavery but the central government’s oppressive power, against which the South wished only to exercise its constitutional right to secede — is clearly false. But there is a great deal of truth to the military component. The South did fight at a material disadvantage, and Lee overcame immense odds on battlefield after battlefield.

There is one great irony of Lee’s life that Guelzo does not address, one I have pointed out in the past. In June 1862, when Lee assumed command of what would soon be called the Army of Northern Virginia, the Confederacy was on the brink of defeat. Union forces had advanced deep into western Tennessee and the Mississippi Valley, and a Union army was at the gates of Richmond. Had Richmond fallen in the spring or summer of 1862 — had Lee not changed the character of the war by inflicting defeat after defeat on Union forces — the rebellion might well have ended then, with the seceded states returning to the Union, possibly leaving slavery intact. The irony is that Lee’s choice to turn against the Union and his subsequent prowess forestalled this outcome. And so by ending slavery, the war made the Union, in Lincoln’s phrase, “worthy of saving.” It is the sort of occurrence that summons up the idea of Providence.

In a short review, it is impossible to do justice to Guelzo’s splendid work. He has done what we ask biographers to do: provide an incisive look at a complex man, neither secular saint nor moral monster. Of course, complexity is the human condition. Thanks to Allen Guelzo for providing the definitive look at the life of a complex man who mostly deserves our respect.

MACKUBIN THOMAS OWENS is senior national-security fellow of the Foreign Policy Research Institute (FPRI) in Philadelphia, editing its journal Orbis from 2008 to 2020. A Marine Corps infantry veteran of the Vietnam War, he was a professor of national-security affairs at the U.S. Naval War College from 1987 to 2015. He is the author of US CIVIL–MILITARY RELATIONS AFTER 9/11 : Renegotiating the Civil-Military Bargain .

We leave the final verdict to those who read and understand history.

The book is

Robert E. Lee: A Life ,

by Allen C. Guelzo

www.washingtonpost.com /outlook/a-southerner-who-abandoned-the-lost-cause/2021/02/04/5d01effc-5031-11eb-bda4-615aaefd0555_story.html

A Southerner who abandoned the Lost Cause

John Reeves 6-8 minutes 2/4/2021

In January 1872, Jubal Early, a former Confederate corps commander, delivered an address at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Va., to honor Robert E. Lee, who had recently died. Believing that Lee was one of the finest military leaders in history, Early declared, “Our beloved Chief stands, like some lofty column which rears its head among the highest, in grandeur, simple, pure and sublime, needing no borrowed lustre; and he is all our own.” In subsequent years, Early and several elite ex-officers would deify Lee while creating the Lost Cause interpretation of the Civil War. According to that view, the war wasn’t about slavery but rather states’ rights. And the North won only because of its superior resources. An additional tenet is that Lee was the greatest soldier in the war on either side.

At the same time the Lee myth was being created, former rebels began reinforcing white supremacy all across the South. In Walton County, a rural community in Georgia, the Ku Klux Klan terrorized freedmen after the war. In 1871, Jake Daniels, an African American blacksmith from the county, was killed by 20 disguised men after refusing to repair a buggy for a White man, who still owed him money from previous jobs. The Klansmen showed up at Daniels’s door in the middle of the night. Daniels went outside but quickly recognized the danger. He tried to reenter his house but was shot in the back of the head. The men then shot him five or six more times before leaving the scene.

This type of violence was not uncommon in the South in the 19th and 20th centuries. In Georgia alone, 589 people were lynched between 1877 and 1950. As Ty Seidule writes in his powerful new book, “ Robert E. Lee and Me ,” “If Lee and Confederate worship created one side of the white supremacy coin, violent terror to enforce racial domination provided the other side.”

Seidule tells the story of his transformation from a believer in the Lost Cause to a critic. Growing up in Virginia and Georgia, he worshiped Lee. It was only later, as the head of the history department at the U.S. Military Academy, that he discovered the truth about Confederate myths. Seidule writes: “I grew up with a lie, a series of lies. Now, as a historian and a retired U.S. Army officer, I must do my best to tell the truth about the Civil War, and the best way to do that is to show my own dangerous history.”

Seidule has written a vital account of the destructiveness of the Lost Cause ideology throughout American history. He shows how films, textbooks and memorials promoted white supremacy by glorifying traitors and enslavers like Lee and other Confederate leaders. Perhaps the best attribute of this fine book is the author’s honesty. When talking of his personal metamorphosis, he vows to “quit hiding behind the impartial, know-it-all historian and open up about the southerner, the boy who grew up on Lee idolatry, and the man who wrapped his identity around the heroes of the Confederacy. Be honest. Be vulnerable. Above all, tell the truth.”

Initially, telling the truth mustn’t have been easy for Seidule, who admits, “I grew up on the evil lies of the Lost Cause.” His early life was shaped by white supremacy at every turn. Seidule, whose father was a teacher, lived for a while on the campus of a school in Alexandria, Va., that one historian called a “Lost Cause denominational high school.” Later, he attended George Walton Academy in Monroe, Ga. — a school that had one purpose, according to Seidule: “Ensure white kids didn’t have to go to school with Black kids.”

It would be many years before he learned of the racial terror that persisted in Monroe after the Civil War. After a quadruple lynching in 1946, The Washington Post published an op-ed describing Monroe as “lynchtown.” Eventually, Seidule attended Washington and Lee University, where Lee served as president from 1865 to 1870 (when the institution was called Washington College). Remarkably, the school still has a chapel dedicated to the former rebel chieftain, with a statue of Lee prominently displayed. As Seidule dryly notes, “My school worshipped Lee, literally.”

The key to Seidule’s rejection of the Lost Cause was his realization, while teaching military history at West Point, that the Confederate leadership committed treason “to protect and expand chattel slavery.” As a scholar, Seidule could no longer make excuses for the violent and degrading slave culture of the South. Describing an antebellum plantation, he imagined “coffle, rape, torture” and came to believe that plantations should be called “enslaved labor farms” instead. He also points out that there were eight colonels from Virginia in the U.S. Army on the eve of the war. Seven remained loyal to their oath, while only one, Lee, betrayed his country. The common belief that Lee did what every other Southern officer did isn’t true. “We must remember,” Seidule reminds us, “Lee fought for perpetual slavery.”

While at the U.S. Military Academy in 2006, Seidule had an “aha!” moment that revealed an important question, if not the answer: Why were there so many monuments to Lee at West Point? He headed to the archives to learn more. From his research, he gained an invaluable insight: A barracks had been named after Lee just one year after 44 Black cadets entered the academy. “I have no ‘smoking gun’ that academy officials named Lee Barracks because of the tenfold increase in African Americans,” he writes, “but I keep finding Confederate memorialization whenever West Point increases integration.”

Seidule noticed a similar process in Virginia during the 1960s and 1970s. Just as the state was being pushed toward integration, it began introducing textbooks that inculcated the Lost Cause view of the Civil War. “The Virginia textbooks formed one of the most powerful testaments to white supremacy, an insidious monument that poisoned children’s minds for a generation,” he writes.

It’s difficult to imagine a more timely book than “Robert E. Lee and Me.” At this pivotal moment, when we are debating some of the most painful aspects of our history, Seidule’s unsparing assessment of the Lost Cause provides an indispensable contribution to the discussion. “We find it hard to confront our past because it’s so ugly,” Seidule concludes, “but the alternative to ignoring our racist history is creating a racist future.”

Robert E. Lee and Me

A Southerner’s Reckoning With the Myth of the Lost Cause

St. Martin’s.

291 pp. $27.99

An interesting and balanced book. Thanks for sharing the review.

traitor.

That is accurate.

Lee was a traitor and slaver, simple as that.

He would have been much better off following the actions of Robert Carter III and the gift of deed when it came to owning slaves.

One of the most objectionable things Lee said, in my opinion is when he told his wife, in a letter, that slavery would end in God's good time. (Not his exact words, but that was the meaning.)

How was Lee to keep his humble home up all alone?

The left is still trying to rewrite its racist past, which continues into the present.

that argument today is yet another lost cause...

I do not understand that statement given the context of the book that Vic presented.

History is not cast in bronze; it is writ in words of generations past, present and yet to come … it is organic and at its best, revisionist; the last page of one historian always leading to the first page of another. These are the true monuments, not the bronzes which are at best book jackets with a synopsis of ‘I was here’.

Nor is it to be trivialized or distorted by ideologues.

Ideologues sport a variety of beards ... it can be hard to differentiate between Lenin and Durham.

Looks like an interesting, nuanced book. Good to see something more thought out and reactionary than thinking one word captures a person.