Coffee under threat Will it taste worse as the planet warms?

Coffee drinkers could face poorer-tasting, higher-priced brews, as a warming climate causes the amount of land suitable for coffee production to shrink, say scientists from London’s Kew Gardens.

Coffee production in Ethiopia, the birthplace of the high quality Arabica coffee bean and Africa’s largest exporter, could be in serious jeopardy over the next century unless action is taken, according to a report , published today.

“In Ethiopia and all over the world really, if we do nothing there will be less coffee, it will probably taste worse and will cost more,” Dr Aaron Davis, coffee researcher at Kew and one of the report’s authors, told the BBC.

Consumption is forecast to outstrip production for the third consecutive year, according to figures from the intergovernmental body for coffee, the International Coffee Organization (ICO). So far, stockpiles accumulated in high production years have avoided any coffee shortages or price hikes.

But as exporters have been forced to tap into those supplies, their stock levels of coffee are currently low, the ICO says. Longer-term climate change worries aside, initial fears about this year’s weather in Brazil and Vietnam, the world’s two biggest coffee producers, have eased. Concerns remain though that any unforeseen weather events there in the next few months may mean a short-term bean shortage.

However, it is the longer-term outlook that is a greater cause for concern to farmers and coffee drinkers alike.

As Dr Tim Schilling, director of the World Coffee Research institute , an organisation funded by the global coffee industry, says: "The supply of high-quality coffee is severely threatened by climate change, diseases and pests, land pressure, and labour shortages - and demand for these coffees is rising every year". In some coffee areas, temperatures have already risen enough to begin having quality impacts, he adds.

“The logical result of that is that prices will need to rise, especially for the highest quality coffees, which are the most threatened,” he adds.

Consumption is forecast to outstrip production for the third consecutive year, according to figures from the intergovernmental body for coffee, the International Coffee Organization (ICO). So far, stockpiles accumulated in high production years have avoided any coffee shortages or price hikes.

But as exporters have been forced to tap into those supplies, their stock levels of coffee are currently low, the ICO says. Longer-term climate change worries aside, initial fears about this year’s weather in Brazil and Vietnam, the world’s two biggest coffee producers, have eased. Concerns remain though that any unforeseen weather events there in the next few months may mean a short-term bean shortage.

However, it is the longer-term outlook that is a greater cause for concern to farmers and coffee drinkers alike.

As Dr Tim Schilling, director of the World Coffee Research institute , an organisation funded by the global coffee industry, says: "The supply of high-quality coffee is severely threatened by climate change, diseases and pests, land pressure, and labour shortages - and demand for these coffees is rising every year". In some coffee areas, temperatures have already risen enough to begin having quality impacts, he adds.

“The logical result of that is that prices will need to rise, especially for the highest quality coffees, which are the most threatened,” he adds.

Ethiopia: The home of coffee

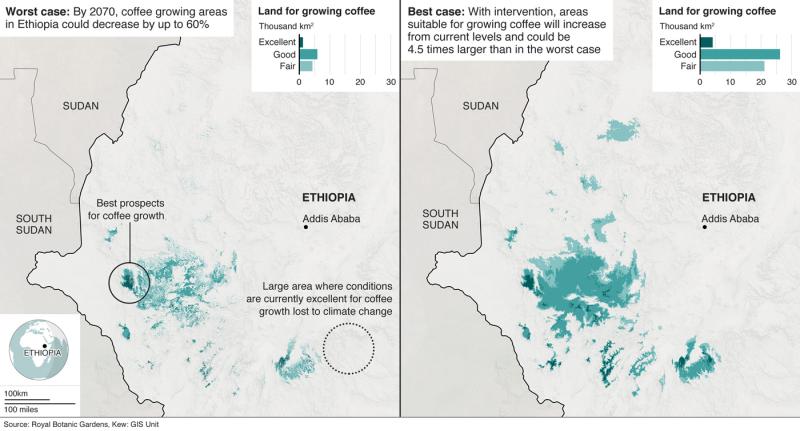

Current coffee growing areas in Ethiopia could decrease by up to 60% given a temperature rise of 4C by the end of the century, the study by Kew Gardens and collaborators in Ethiopia predicts.

The 4C temperature increase is based on a scenario in which greenhouse gas emissions remain high from now until 2100. The forecast is one of the high-range greenhouse gas emission forecasts from the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

However, even when testing using a more conservative climate change scenario, the current coffee growing areas in Ethiopia would still shrink by 55%, Kew say.

“A 'business as usual' approach would be disastrous for the Ethiopian coffee economy in the long-term,” say’s Kew’s Justin Moat, another of the paper’s authors.

I can't support or provide for my family Jamal Kasim, Ethiopian coffee farmer

But Kew’s researchers are keen to stress that if action is taken, this situation can be avoided. Relocation of coffee-growing areas, combined with forest conservation and replanting, could see substantial growth in the area suitable for growing coffee in Ethiopia.

“There is the potential to mitigate some of the negatives and actually increase the coffee-growing area by four-and-a-half-times compared with maintaining the status quo,” Dr Davis says.

Coffee provides a livelihood for close to 15 million Ethiopians, 16% of the population.

Farmers in the eastern part of the country, where a warming climate is already impacting production, have struggled in recent years,and many are currently reporting largely failed harvests as a result of a prolonged drought.

In the past 10 years, farmer Jamal Kasim has noted significant changes to his coffee harvest.

"In the first few years they bore a lot of fruit, but now they've become barren. I can't support or provide for my family," he says.

Brazil: The world's top coffee producer

Ethiopia may not be alone in experiencing potential problems with its coffee production. Research published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) , a United Nations-backed expert panel, outlines similar worries for Brazil.

For the past three years we have had rain levels below the average and the crops are suffering Inacio Brioschi, Brazilian coffee grower

A 3C rise in temperature and a 15% increase in rainfall from pre-industrial levels in two of the country’s major coffee-producing states, Minas Gerais and Sao Paulo, could see the potential area for production dwindle from 70-75% to 20-25%.

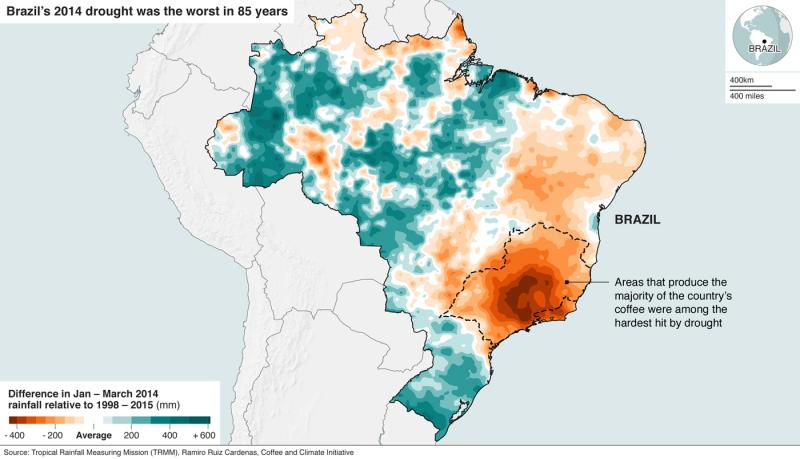

In the last few years, the worst drought in Brazil since records began almost a century ago has plagued the country’s main coffee-growing regions. Earlier this year, Brazil’s government went as far as discussing the possibility of importing coffee beans for the first time, but abandoned plans following opposition from producers.

Production of the higher quality Arabica bean took a hit in the year from July 2014 to June 2015. Prolonged dry spells coupled with high temperatures in the state of Espirito Santo in the two years since have also resulted in lower harvests of the more bitter Robusta bean.

And even now, across the region, reservoirs used by farmers to water their crops remain dry. State officials banned or restricted the use of irrigation in a number of towns during periods of extreme drought, while construction of new reservoirs to ensure water is stored more efficiently during rainy spells is ongoing.

“For the past four years, we have had rain levels way below average. The crops are suffering,” says Inacio Brioschi, a coffee farmer from Espirito Santo.

Brioschi lost half his crop in 2016 and expects production to be 60% below average this year.

A single drought cannot be attributed to climate change, stresses Dr Peter Baker, of the Coffee and Climate initiative, a body funded in part by the coffee industry. However, these extreme weather events constitute a major challenge for the coffee industry.

"It's not just the fact that temperatures are going up steadily, these major climatic events that can last for months are most damaging," Dr Baker says.

Climate-modelling studies support the idea the more extreme temperatures are arising from climate change, according to Richard Betts, head of climate impacts research at the UK Met Office's Hadley Centre.

Droughts coupled with rising temperatures overall means weather events have a greater impact, he says.

"With temperatures rising across the globe, it's fair to say that when droughts occur, their effects are often more intense due to the warming driving more evaporation and drying the land more," Mr Betts says.

Can technology safeguard coffee's future?

While severe weather is impacting coffee farmers in Ethiopia and Brazil and scientists are forecasting a reduction in areas where high-quality coffee can grow, a number of coffee-growing countries are seeing record harvests. The reason, Dr Baker believes, is deforestation.

“In nearly all countries where coffee production is currently expanding rapidly, deforestation is the primary source of new coffee lands. That’s apart from Brazil, where technological improvements can account for any productivity increases,” he says.

In the long term, technology could play an even more important role in ensuring the future of coffee.

In 2014, the complete genome sequence for Arabica was made public, making it easier to select plants able to cope with warmer conditions.

In addition, the World Coffee Research institute is working on a plant breeding programme to “recreate” the Arabica coffee with “better breeding” to increase its diversity, making it more resistant to climatic changes.

But this is not something that will happen overnight – and by then caffeine lovers could face rising prices and declining quality at their favourite coffee shop.

Credits

Design by Tom Nurse, James Offer and Luke Keast. Development by Steven Connor and Becky Rush. Images and videos by Colin Cosier and Rafael Barifouse. Other imagery by Getty. Additional video production by Joe Inwood and Vladimir Hernandez. Written and produced by Nassos Stylianou and John Walton. Brazil satellite images from the Nasa Earth Observatory, captured by Landsat.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-fa38cb91-bdc0-4229-8cae-1d5c3b447337

As the climate changes coffee will become more scarce and more expensive. Someday in the not to distant future it will become a luxury item, like a fine Brandy.

Egads... I need my coffee. I do think that a lot of coffee still comes from S. America though.

I think so too, but if the growing areas shrink, then we'll be getting the bulk of our coffee from Ethiopia. I wonder how it will taste?

The coffee I can buy here tastes like shit anyway. Believe or not, tea can pack more caffeine in a cup than coffee, as it happens.