Romans 13 and the Gettysburg Address

This is a good piece from Robert L. Tsai on “ The Anti-Immigration Bible .” Tsai gives a good overview on the way nationalist Christian groups have traditionally used the Bible to support their nationalism, including their tendency to focus — as Jeff Sessions has — on Nehemiah and Ezra. Such “wall-building” enthusiasts rarely point out, as Tsai does, that the stories of Ezra and Nehemiah end in full-blown ethnic cleansing, including mass divorce and family separation.

Ezra was a monster . Worse than Ahab and Jezebel. There’s a reason so much of the rest of the canon goes out of its way — implicitly and explicitly — to reject and condemn the cruelty of Ezra and Nehemiah’s sins there in Sessions’ pet passage.

One quibble with Tsai, and with most of the rest of the reporting on Sessions’ and Sarah Huckabee Sanders’ attempted appropriation of Romans 13 last week. Tsai writes:

Last week Attorney General Jeff Sessions invoked the Bible to justify a policy that has separated nearly 2,000 border-crossing children from their parents in a mere six weeks. Referencing Romans 13, he stated that everyone must “obey the laws of our government, because God has ordained the government for his purposes.”

But note the full enormity of what Sessions is doing there. He’s not just invoking the Bible to justify this one policy, but to justify — as beyond question and beyond criticism — any and every policy . Yes, specifically he’s claiming the divine right to put children in cages, but more than that he’s claiming to be an agent of God and therefore that whatever he does is divine, and that we mere mortals have no choice but to submit and obey.

Apart from his piss-poor theology and his blood-and-soil hermeneutics, there’s another, deeper, problem with the way Sessions invoked this passage. He cited it as being about some entity called “the government,” by which he meant himself — the Trump Administration, politicians in general. This entity, in Sessions’ view, is a thing separate and distinct from — over and above — the rest of us. We’re subjects to the authority of the government. We are accountable to it, not the other way around.

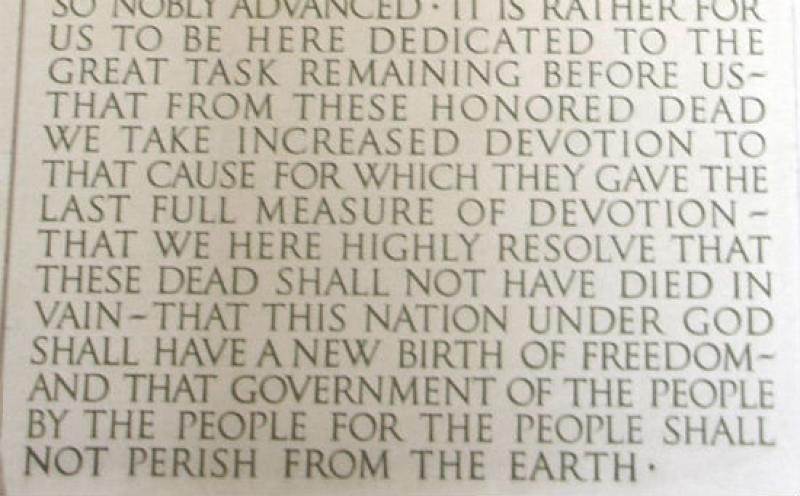

The idea of “the government” that Sessions is asserting — and attempting to sanction with scripture — is not compatible with the idea stated by our greatest Founding Father, Abraham Lincoln, in the Gettysburg Address: “government of the people, by the people, for the people.”

I appreciate that it’s largely viewed as naively idealistic to cite that lovely phrase as anything other than a pipe dream. It’s embarrassingly un-savvy to suggest that it corresponds to anything real or that it could ever be expected to. But this is the ambitious, and necessary idea that has to be asserted and reasserted and continually made more real if we want to live in anything approximating a democracy. The alternative, assumed there in Session’s scriptural grasping at the role of Caesar, is to be subject to the authority of rulers and kings. Nothing serves the Men Who Would Be Kings more than the archly knowing dismissal of the idea of self-government as helplessly naive.

Anyway, my point here is less about American governance than about Christian political thinking, nearly all of which is based on the assumption that “government” is always a matter of kings and rulers and Caesars. This is true not only of reactionary, semi-theocratic theologies, but also of more left-ish, progressive theologies — Anabaptist-y anarchy, Empire criticism, and the like. Whether it regards “The Government” as a divinely ordained ruler or as a beastly oppressor, it tends to present it as some separate entity over there, wholly distinct from us folks over here.

The New Testament writers had a lot to say about our accountability to government — as in both Romans 13 and Revelation 13. Their world did not include the need, or the possibility, of having much to say about government’s accountability to us. But that’s how it’s supposed to work here and now. We don’t have a king or a Caesar, we have us . We are, in this time and place and in this system — however imperfectly realized — the authorities appointed as servants of God to do good.

We must not irresponsibly reject that appointment by reading Romans 13 as though we were first-century subjects of an all-powerful emperor. We shouldn’t be reading that passage for wisdom about our accountability to government, but for wisdom about our accountability as government.

Otherwise we’re conceding the argument to Jeff Sessions and other would-be rulers claiming a divine right to demand our submission. That will make us accountable to him to obey whatever he tells us about children in cages. We need to turn that around. We need to demand that he be accountable to us, and that if what he does is wrong he should fear us, for we have authority and we do not bear it in vain.

See earlier: “Of, by, for”

Tags

Who is online

59 visitors

Like most bibliolaters, our local NT contingent attempts to elevate various verses above Christ's One Commandment . While "Love one another" is an idea that is obviously intemporal... "render unto Caesar" is just as obviously tied to Jesus's epoch... two thousand years ago ...

This is cherry-picking carried to its

highestlowest level...We can lock our doors while opening our borders.

The two have nothing to do with one another.

Sorry, wrong thread...I beg your forgiveness.

But why should we have open borders? Hillary called for that and it's one of the reasons she lost.

Lemme think about it...

I'm not for "open borders" because immigration must be orderly. There are several reasons to raise legal immigration significantly:

- It's the humane thing to do.

- It's better to have controlled immigration than uncontrolled. And they will come regardless.

- American demographics show a need for immigration, as Boomers die off.

- Since there are good reasons to allow immigration, it's particularly stupid to spend enormous sums to prevent it.

I would go one step beyond that offered by Tsai. I say that we should use our ('God-given') brains and relegate the wisdom of the ancient authors of the Bible to that of (relatively) naïve (albeit wise for their time) individuals who wrote based on an agenda. Forget this entirely unsupported Bible is divine nonsense and operate based on contemporary, well-supported information.

So yes there might be a God; it is possible. But if there is a God we do not know anything about this entity nor do we know what it expects of us. So given the absolute lack of information about God maybe the smartest thing we can do is not blindly accept what ancient men have written but rather make decisions based on the best possible contemporary information and our best efforts at objective reasoning.

Seems like a good way to operate (to me).

So... I've spent a few minutes thinking about your post...

My first reaction was, "Oh. OK. ... Rejection en bloc of the Bible as a reference is a reasonable, coherent reaction.

... ... ... but

Then I wondered, "If the Bible is rejected, does that mean that all references are rejected?" Why should any other reference be more pertinent, accurate, whatever... ? If you reject the Bible, then some other person may likewise reject any other reference that is suggested.

Ultimately, is rejecting any particular reference out of hand equivalent to rejecting all references... ??

And how do we begin to navigate without any references at all?

Perhaps it would be better to examine each reference in order to retain whoat is worthwhile, while rejecting what is not. Including... but not limited to... the Bible.

"... as a divine reference ..." is more precisely to my point. I would think a book must first be shown to be divine before it can be properly considered divine. Until the Bible is shown (reasonably speaking) to be divine I will consider it to be a book written by ancient men (that much we do know).

If someone were to suggest the Iliad is divine I would reject it as such due to the lack of evidence supporting the claim. If someone were to offer the Iliad as ancient poetry I would accept that based on the evidence.

IMNAAHO, inerrancy is quickly shown to be logically untenable. So it's easy to reject the Bible as a blueprint.

It remains that the Bible can be a useful reference for other reasons. It describes the epoch, obviously. And various types of linguistic analysis can separate the various authors (and their agendas).

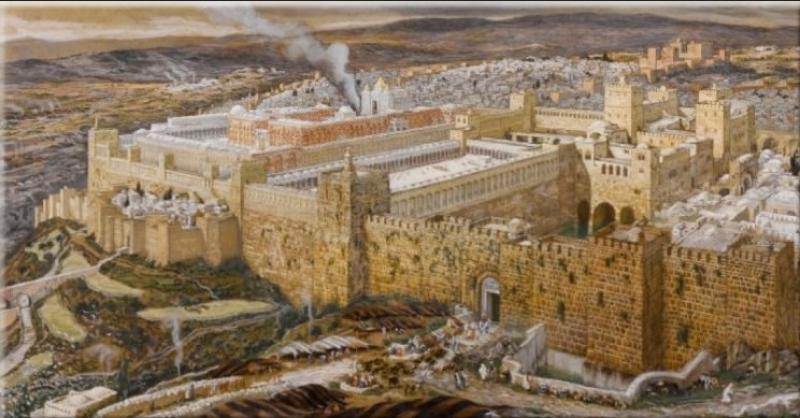

It seems to me that it would be a great waste to not use the Bible as a reference for 1st century Palestine.

I agree. Stated differently in my original post: