Evolution tells us we might be the only intelligent life in the universe

![]()

Author: Nick Longrich - Senior Lecturer, Paleontology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Bath

Article is authorized to be reproduced under Creative Commons license from source

Are we alone in the universe? It comes down to whether intelligence is a probable outcome of natural selection, or an improbable fluke. By definition, probable events occur frequently, improbable events occur rarely – or once. Our evolutionary history shows that many key adaptations – not just intelligence, but complex animals, complex cells, photosynthesis, and life itself – were unique, one-off events, and therefore highly improbable. Our evolution may have been like winning the lottery … only far less likely.

The universe is astonishingly vast. The Milky Way has more than 100 billion stars, and there are over a trillion galaxies in the visible universe, the tiny fraction of the universe we can see. Even if habitable worlds are rare, their sheer number – there are as many planets as stars , maybe more – suggests lots of life is out there. So where is everyone? This is the Fermi paradox . The universe is large, and old, with time and room for intelligence to evolve, but there’s no evidence of it.

Could intelligence simply be unlikely to evolve? Unfortunately, we can’t study extraterrestrial life to answer this question. But we can study some 4.5 billion years of Earth’s history, looking at where evolution repeats itself, or doesn’t.

Evolution sometimes repeats, with different species independently converging on similar outcomes . If evolution frequently repeats itself, then our evolution might be probable, even inevitable .

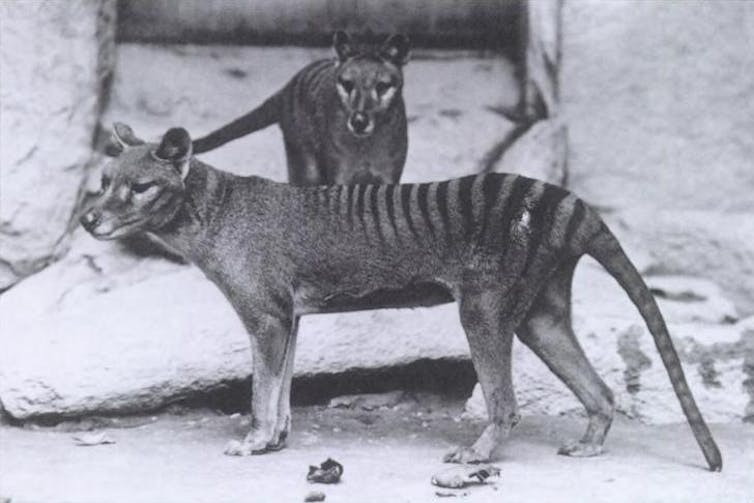

The wolf-like thylacine. Wikipedia

The wolf-like thylacine. Wikipedia

And striking examples of convergent evolution do exist. Australia’s extinct, marsupial thylacine had a kangaroo-like pouch but otherwise looked like a wolf, despite evolving from a different mammal lineage. There are also marsupial moles, marsupial anteaters and marsupial flying squirrels. Remarkably, Australia’s entire evolutionary history, with mammals diversifying after the dinosaur extinction, parallels other continents.

Other striking cases of convergence include dolphins and extinct ichthyosaurs, which evolved similar shapes to glide through the water, and birds, bats and pterosaurs, which convergently evolved flight.

Squid eye. PLoS Biology

Squid eye. PLoS Biology

We also see convergence in individual organs. Eyes evolved not just in vertebrates, but in arthropods, octopi, worms and jellyfish. Vertebrates, arthropods, octopi and worms independently invented jaws. Legs evolved convergently in the arthropods, octopi and four kinds of fish (tetrapods, frogfish, skates, mudskippers).

Here’s the catch. All this convergence happened within one lineage, the Eumetazoa. Eumetazoans are complex animals with symmetry, mouths, guts, muscles, a nervous system. Different eumetazoans evolved similar solutions to similar problems, but the complex body plan that made it all possible is unique. Complex animals evolved once in life’s history, suggesting they’re improbable.

Surprisingly, many critical events in our evolutionary history are unique and, probably, improbable. One is the bony skeleton of vertebrates, which let large animals move onto land. The complex, eukaryotic cells that all animals and plants are built from, containing nuclei and mitochondria, evolved only once. Sex evolved just once. Photosynthesis, which increased the energy available to life and produced oxygen, is a one-off . For that matter, so is human-level intelligence. There are marsupial wolves and moles, but no marsupial humans.

The vertebrate skeleton is unique. Smithsonian Institution

The vertebrate skeleton is unique. Smithsonian Institution

There are places where evolution repeats, and places where it doesn’t. If we only look for convergence, it creates confirmation bias. Convergence seems to be the rule, and our evolution looks probable. But when you look for non-convergence, it’s everywhere, and critical, complex adaptations seem to be the least repeatable, and therefore improbable.

What’s more, these events depended on one another. Humans couldn’t evolve until fish evolved bones that let them crawl onto land. Bones couldn’t evolve until complex animals appeared. Complex animals needed complex cells, and complex cells needed oxygen, made by photosynthesis. None of this happens without the evolution of life, a singular event among singular events. All organisms come from a single ancestor; as far as we can tell, life only happened once .

Curiously, all this takes a surprisingly long time. Photosynthesis evolved 1.5 billion years after the Earth’s formation, complex cells after 2.7 billion years , complex animals after 4 billion years , and human intelligence 4.5 billion years after the Earth formed. That these innovations are so useful but took so long to evolve implies that they’re exceedingly improbable.

An unlikely series of events

These one-off innovations, critical flukes, may create a chain of evolutionary bottlenecks or filters . If so, our evolution wasn’t like winning the lottery. It was like winning the lottery again, and again, and again. On other worlds, these critical adaptations might have evolved too late for intelligence to emerge before their suns went nova, or not at all.

Imagine that intelligence depends on a chain of seven unlikely innovations – the origin of life, photosynthesis, complex cells, sex, complex animals, skeletons and intelligence itself – each with a 10% chance of evolving. The odds of evolving intelligence become one in 10 million.

Photosynthesis, another unique adaptation. Nick Longrich

Photosynthesis, another unique adaptation. Nick Longrich

But complex adaptations might be even less likely. Photosynthesis required a series of adaptations in proteins, pigments and membranes. Eumetazoan animals required multiple anatomical innovations (nerves, muscles, mouths and so on). So maybe each of these seven key innovations evolve just 1% of the time. If so, intelligence will evolve on just 1 in 100 trillion habitable worlds. If habitable worlds are rare, then we might be the only intelligent life in the galaxy, or even the visible universe.

And yet, we’re here. That must count for something, right? If evolution gets lucky one in 100 trillion times, what are the odds we happen to be on a planet where it happened? Actually, the odds of being on that improbable world are 100%, because we couldn’t have this conversation on a world where photosynthesis, complex cells, or animals didn’t evolve. That’s the anthropic principle : Earth’s history must have allowed intelligent life to evolve, or we wouldn’t be here to ponder it.

Intelligence seems to depend on a chain of improbable events. But given the vast number of planets, then like an infinite number of monkeys pounding on an infinite number of typewriters to write Hamlet, it’s bound to evolve somewhere. The improbable result was us.

Simple life might be common, but advanced, intelligent life?

Intelligent life might be less common, but still probable.

Statistically, there is no doubt that it exists. Anyone claiming otherwise fails to comprehend just how big the universe is.

There are estimatedly 100,000,000,000 stars in our galaxy.

There are estimatedly 1,000,000,000,000 galaxies in the universe.

There are therefore estimatedly 100,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 stars in the universe.

Now multiply that number by whatever you think the average number of planets per star are.

Indeed. We already know with 100% certainty life exists in the universe, namely Earth. We know Earth has abundant life in a variety of environments where said life evolved and even thrived. Using Earth a point of reference, and with an infinite universe, it's highly likely life exists elsewhere in the universe.

No doubt? None at all? I mean, statistically speaking, we only have conclusive evidence of life on one little world so far. Weighed against the entire universe those aren't very good odds. Granted, we know next to nothing about potentially life-supporting environments in the rest of our own galaxy, let alone the universe, but based solely on what we actually do know at present can we really say no doubt?

The Fermi Paradox has quite a bit of merit to it. With the universe being almost 14 billion years old, and our own Milky Way galaxy about 13.5, then if there really have been other instances of complex, intelligent, tool-making, technological life like us, then where are they? Given how much time passed before our solar system even existed, there should be technologically advanced civilizations everywhere. There should have been a technological equivalent of the Cambrian explosion across the entire galaxy. Once technology reached a point that allowed any given species to leave its immediate environment they should have exploded everywhere (just like life did here on Earth when biology (instead of technology) reached a certain level of development in the Cambrian). Even if they are only a few million years older than us (when they could be billions), there should have been more than enough time to get everywhere. The Milky Way is only 100,000 light years or so in diameter. They wouldn't even have needed any kind of sci-fi-esque faster than light travel. Low-end sub-light speeds would have done it by now. They should be as prevalent throughout the galaxy as life is on Earth, and life is damn near everywhere on Earth.

Don't get me wrong. I'm not saying they couldn't be out there at all, but like Fermi said, where the hell is everybody?

And on the 1st world that we looked at.

Fermi Paradox has no merit other than a debate point. Fermi Paradox makes the assumption that we would know how aliens communicate and would actually recognize it as communication.

FRB's, alien communication?

Gravitational waves as communication? We can barely detect the strongest waves in the universe.

Something we have not even discovered yet? Quantum physics is showing great promise with superposition, but we would never recognize anything like it as communication at this stage of development.

'No doubt' is clearly too strong since it implies certainty and we have zero supporting evidence of exolife. What we do have, however, is proof that life can exist on at least one planet and to the very best of our scientific knowledge the universe appears to be operating under consistent underlying rules (physics). Thus with such an unfathomably large space populated with ~1021 (sextillion) planets and approximately 13.8 billion years of time and the same physics at play, there is good reason to be optimistic that life of some form exists elsewhere.

Since you are using the time span of 13.8 billion years means the assumption of the big bang, which would mean for life to form ( as we believe so far) we would need to trim a few billion years off that number in which life could even have a chance to start. Another few billion may need to be trimmed off just to get enough building blocks from novas to get the heavier elements required for life, so it is possible that we are the first or among the first intelligence in the universe.

Life formed on our planet within 1 billion years. And we do not have any reason to think that it takes even that long. It might, but we have no basis on which to say it does.

Yup, Carbon comes later in the life cycle. The oldest know star, HIP 11952, is estimated at 12.8 billion years and it has two planets. We do not know for certain when Carbon first formed in the universe.

It certainly is possible. But life could be forming in parallel and there are many billions of years of development time prior to our solar system even showing up.

Given that we might all be at somewhat the same place, time and space are the enemies of us meeting.

And even on this planet, there were many different intelligent (to varying degrees) humanoids. Neanderthal was just as improbable or probable as Homo Sapiens.

We have not figured out how to get to the other end of our solar system, so what you should be asking is how probable is it that there are beings more intelligent than us.

But then again, maybe they have been here and thought us no more worthy than we think an ant is. That is a possibility too.

But that's irrelevant. That would be true either way, whether there's other intelligent life out there or not.

Is this subject not a debate? It's a conversation of competing hypotheticals, anyway. If other intelligent life is out there, and even if it's just a little bit older and a little more advanced than we are, then they should be all over the place.

Hell, we could be at a level of technology that would allow us to live permanently off-world in just another century or so. Add another century to make long, interstellar journeys feasible and the stage will be set for us to spread across the entire galaxy. By the time a million years has passed there could be trillions upon trillions of our descendants all over the Milky Way.

The kind of big structures we'd be building to do that wouldn't just disappear. After a million years of exploration and colonization there should be a million years of space junk in orbit of every star we go to, and plenty of abandoned structures and evidence of resource extraction on the surfaces of various rocky planets and asteroids. Hell, we'd likely still be in the vicinity.

So if there's supposed to be lots of intelligent life out there - I mean, if it's supposed to be the norm, then they've already had millions, if not billions of years to leave behind plenty of evidence of their activity right here in our own backyard. Especially in places without weather to erase traces of it over time, like the Moon or Mars. After all, we have an attractive solar system. Our star is more powerful than most (which are red dwarfs) so solar energy is very abundant. We have high elemental complexity throughout, lots of heavy elements and water. Surely some of that presumably abundant intelligent life would have come here after all of this time, and surely we would have noticed some evidence of it by now, right?

Possible, I suppose, but we almost have them figured out as a natural phenomenon - Astronomers now think they can explain fast radio bursts.

Pointless. You'd need to manipulate lots and lots of mass, which would be highly inefficient, and gravity is restricted to the speed of light anyway, just like everything else. Might as well use light.

I'd go with that one. Absolutely.

But communication aside, like I said above, activity over potentially very long periods of time (possibly billions of years) would leave other kinds of evidence all over the place, material evidence. We have none.

Unless the rumors about Roswell and Area 51 are true.

If we could only get past the problem of unfathomable distance we might come across some of that evidence.

I was trying to say that it shouldn't be hard. If intelligent creatures like us are assumed to be a common, natural product of life and evolution, then given the age of the galaxy there should be some material evidence right here in our own immediate vicinity. Our solar system is younger than the galaxy itself and still has a strong, hot sun and a full Periodic Table of stable elements. We're young enough to still have plenty of heavier, unstable elements as well. Older regions with older material from older supernovae don't have the same metalicity. We should be an attractive destination. So, if exo-intelligence is not supposed to be in doubt, then it should have exploded across the galaxy long before now. It should be here in our own system. At the very least there should be material evidence, maybe on Mars or the Moon, or being dragged along in a Lagrange point or two. We should be able to see it. It should be obvious because there should be so much of it after so much time.

The fact that we don't see it locally after billions of years of possible habitation should, to me at least, be taken as some pretty good evidence that even if simple life is common in the universe, advanced creatures like us might not be. Especially considering the evolutionary one-off flukes mentioned in the article.

Finding evidence of primitive exolife is very difficult to do since we have to take physical samples. Intelligent exolife would be easier but we still need to get close enough to the planetary body to detect the evidence. Technologically advanced exolife, however, would have a much broader range and we should be able to detect evidence via electromagnetic patterns.

But we must have our detecting instruments trained at the right spot. One analogy offered for how much of the universe we have explored is a glass of water out of the ocean. If the ocean is the universe, we have directly looked in a single glass of its water. The universe (like the ocean) might be full of life, but sporadic and out of range of our detection methods.

Yeah, but it was fun to say....

Yes it is, but we are debating the reality of it, aren't we? The Fermi Paradox (which I have always had problems with) leads with one rather large assumption, that alien life isn't really that alien. It assumes that we would understand and comprehend that life and its actions.

Aliens may very well have the equivalent of lighthouses out there broadcasting their existence, trouble is that we may be the equivalent of a "blind" race unable to see those lighthouses.

I read an article recently that stated the exact same thing about FRB's that you just did about them being natural phenomenon, however it also pointed out that we have started seeing repeatable FRB's that would not fall under the natural phenomenon theory.

So, who knows.

You are putting human restrictions on "alien" motivations. Perhaps these aliens have a natural, biological, version of gravity detectors or something else that would make gravitation waves preferable to light. Remember, they're alien...

Also they don't need that much mass or power to create, they just need that much for our current technology to detect. Gravitational waves are everywhere, we just can only see the largest at this time.

Quantum gives me headaches. Double slit experiment took me weeks to get over....

We've only been in space for about 60 years. I did some poking around and found that in that relative blink of an eye we've put thousands of artificial satellites in orbit around Earth. We've sent dozens to other planets, a few asteroids, the sun, and one comet. Aside from that there are thousands of pieces of space junk floating around - boosters and other pieces of spacecraft debris like discarded cowlings. Even a glove. The Space Surveillance Network tracks over 21000 objects larger than 10 cm around Earth.

Again, that's in just 60 years, and the numbers are only going to increase.

So if intelligent biological life like us is assumed to be likely and relatively common, and it does what successful life as we know it tends to do (reproduce, increase population size, and expand everywhere it can survive), then it would have become space faring long ago and had billions of years to reproduce and spread everywhere.

Everywhere, including here.

Billions of years (can't stress that enough).

There should be ancient structures and space junk all over the place right here in our own system. Dead satellites, probes, orbital habitats, orbital solar collectors, scrapped spacecraft, derelict equipment, maybe a glove or two, the kind of stuff that we'd be able to detect and track. We should have noticed it by now, but we haven't. It doesn't seem to be there.

So what is one to conclude? Life like us could be exceedingly improbable and thus exceedingly rare. We really could be the only example in our entire galaxy.

After all, something like 5 billion different species are thought to have evolved in Earth's history (and maybe many, many more), but creatures like us only happened once. Once. Our lineage is the only example on a planet as rich in life as this one is. We're a rarity. A highly successful rarity that has spread across and dominated the entire planet, but still a rarity. A singular rarity in fact (on the tree of life).

If the kind of intelligence that gives rise to highly technical civilizations were a likely, common result of evolution, then we shouldn't even be alone here on Earth. Life has been magnificently rich and successful on this planet, and yet here we are, alone, the only example.

Don't you agree that the odds do not seem to favor creatures like us?

But we're talking about the possibility of biochemical life, right? It would be comprehensible. To leave its natural environment and become space faring it would need things like ships with engines and artificial habitats. It would be building those things out of matter, just like we do. It would need lots of energy, just like we do. Probably much more than we do. Maybe we couldn't comprehend its language or means of communication, or some of its actions, but the physical, material, engineered structures it would require to survive away from its home world would be completely comprehensible to us.

All Fermi's Paradox says is, "Hey, if life is as common as a lot of people think it should be in the universe, and if civilization-building, space faring advanced life is a normal, likely result of biological evolution, then where are all these civilizations hiding? They should be literally everywhere by now, given the extremely long time spans involved."

I'm paraphrasing there, of course, but I don't see why anyone should have a problem with it. It's strikes me as a perfectly sensible question.

You're not alone in that.

In my opinion, intelligent life is rare. It is, however, likely because of the unfathomably large number of environments in our very large universe. In other words, I find it unlikely that in the entire universe the only environment that produced intelligent life is ours. The fact that we exist says that intelligent life is possible. Why would we think it unique?

Why? Our nearest solar system, Alpha Centauri, is about 4.4 light years from us. That is a massive distance for material. Our nearest galaxy, Andromeda, is about 2 million light years away. Those our our neighbors! There are hundreds of billions of galaxies in the universe. Why would we think that this space junk would find its way into our tiny, little speck of the universe (and that we would be able to detect it)?

The fact that our universe can produce creatures like us is very significant. If it can do it once, why not multiple times? I agree that the process is complex and most likely rare, but the number of environments in the universe is staggeringly large. I just do not see it likely that every one of those environments have failed to do what our environment has done.

The odds (speaking in the abstract) do not favor intelligent life because, it seems to me, intelligent life is rare. But the odds that we are unique in the universe seem to be very low.

We're pretty much in agreement, then. Likely to exist elsewhere in the universe, simply because of the sheer number of possibilities, but improbable and thus rare.

I haven't claimed it's impossible, just likely to be a lot more uncommon than many people seem to think.

We don't need to consider other galaxies or the rest of the universe. There are a few hundred billion stars right here in the Milky Way. If civilization-building, space faring intelligence really was a common result of evolution, then even if only a handful of them emerged billions of years ago, we should know about them today. They should have done what all life tends to do - fill every niche possible. Once large, off-world habitats are technologically possible (self-sustaining cities in space, so to speak), then even at low sub-light speeds the entire galaxy becomes accessible over a few million years.

We are almost at that point, ourselves. A permanent orbital habitat is almost possible in the here and now. We know how to simulate gravity, how to make nuclear and solar electricity, how to grow food in artificial environments, how to make bio-reactors for processing waste and air. Everything would need proving and refining over time, of course, but it would really just be a matter of paying for it, mostly the launches. Lifting things to space is hugely expensive, as I'm sure you know, but once someone starts mining the Moon, with the very low lift costs involved, the price could come down dramatically. It might not be that far off, as long as we can hold things together down here and not self-destruct.

It would have been made here. Lots and lots of it. I keep trying to stress the time spans here - potentially billions of years. For context, we've only been a highly technological species for what, a little over half a century? Look at all the junk we've littered space with already. If intelligence really were a common, likely result of basic life and evolution, then even if it was just a little more advanced than we are now it should have been able to spread everywhere, even at low speeds, given the vast lengths of time involved. And it would be making use of available resources along the way, not trying to bring everything along from its point of origin (which wouldn't make any sense at all). Actually, if they ever existed, the life forms themselves should still be here. But they're not, and neither is any evidence of billions of years of potential habitation, so the conclusion should be that they haven't existed yet.

We may be the only ones in this galaxy, or at least some of the first. If others developed before us it would necessarily have been so recently that they haven't had time to migrate everywhere. Otherwise we'd know. The problem is, that doesn't make a lot of sense, considering our solar system is so much younger than the galaxy itself. If intelligence really were likely and common, it should have happened in some older system and started spreading around the galaxy long before our sun ever formed and ignited.

I do not think technologically advanced exolife (TAE) is common; it seems rare and sporadic.

Depends on where they emerged. We cannot detect even their radiation with our current equipment unless it is relatively close and emerging from an area on which we have trained our sensors. It is near certainty, by your argument, that such life is not in our solar system and unlikely to be in nearby solar systems. The further the distance, the less likely we will see any evidence. Our expanding universe makes detection even more difficult (and in many cases the evidence cannot ever get to us).

Understood. Per your argument, given Andromeda is ~10 billion years old, it could have produced TAE billions of years ago and the evidence of same would have plenty of time to reach us. The Milky Way itself is ~13 billion years old with no signs of debris. So it is not likely that this has occurred in our galaxy or in our nearest galaxy Andromeda. That is a fine argument for the rarity of TAE.

Now, that established, I keep emphasizing the size of the (expanding even) playing field. If TAE has existed for billions of years but is billions of light years away (easy enough given the size of our universe ~93 billion light years), even its radiation would be undetected much less physical evidence. At some distances, the evidence can never reach us.

I think intelligent life is likely but not common. But I am speaking of the universe, not just our galaxy (one of ~100 billion), We exist so clearly the laws of physics enables the existence of intelligent life. TAE is less likely largely due to its ability to kill itself. TAE might have happened in an older system but if that system is not close enough to us we would not (and maybe never) see any evidence of it. To your point, plenty of time exists for TAE to develop and spread but the size and expansion of the universe creates barriers for detection. TAE might be in the 'next room' (cosmologically speaking: millions to billions of light years away) but the spacetime wall (and our very limited sensors) prevents detection.

In short, imagine 100 billion dots (each dot is a galaxy). We know that TAE exists (albeit primitive) on one dot. There are ~100 billion more. Is TAE a 1 in 100 billion shot? Given the same physics throughout the universe (best we can tell) I find it quite likely that we are not alone.

[ Note: I am using your argument that we might be the only TAE in our galaxy. Thus I use galaxies (~100 billion) rather than planets (~100 billion galaxies * ~100 billion stars per galaxy * n planets per star) in my example. That is, I am being conservative. ]

Statistically, your view is unsupportable. Or, to put it differently, there aren't any statistics that support your view concerning the likelihood of life, let alone intelligent life.

You list statistics for the likelihood of planetary bodies. We are indeed developing a statistical analysis for the likelihood of such bodies, but it is still in its infancy. We are getting a lot of surprises in this area.

That said, we have zero statistical data on the likelihood of life on those planetary bodies. You cannot build a statistical analysis off the number one. For instance, you can't reach into an enclosed box with a million socks in it, withdraw one, which happens to be blue, and create any sort of statistical model for how many blue socks the box contains. In order to begin creating a statistical analysis, you have to draw again. The more you draw, the more accurate your statistical analysis becomes.

At the moment, the best we can come up with is, based on what we know concerning the requirements for a life sustaining environment, there are X amount of planets that may be suitable for sustaining life. And even that is a very shaky statistic. But even so, that there are X number of planets, statistically, that may be suitable for life does not in any way statistically predict the number of planets that support life. Right now, the argument is simply something like "it stands to reason". That is not a statistical conclusion.

Now, add in intelligent life. That is even less statistically unsupportable because we don't even know (from a purely humanistic perspective) why there is intelligent life on this planet, let alone another. Paleontologically, intelligence is not at all required for a successful species.

In order to build a statistical argument for the probability of life on other planets one must first determine at least one other planet with life on it. Then, having detected that life, one must determine a reasonable answer as to why that planet has life. With that in hand, one can begin to start talking about statistics. Discovering such a planet would give us a direction to look in concerning discovering other such life bearing planets. The more we discover, the firmer our statistical model becomes.

Until that happens, there are no statistics that support the likelihood of other life out there, let alone intelligent life. Sorry, but that's the way statistics work.

Currently it is estimated that there are ~60 billion habitable exoplanets (planets that could host life as we know it based on what we know is required to host life) in our galaxy. Conservatively, there are ~100 billion galaxies. So, based on the data , there might be ~6 trillion habitable exoplanets in the known universe. Ozzwald's argument could thus be stated in question form (and quite a bit more conservatively) as:

Is it likely that all 6 trillion exoplanets are devoid of intelligent life? 0 in 6 trillion?

Dig has made the point that in our own galaxy we have yet to see any evidence of technologically advanced exolife (TAE). Note, that we earthlings are at best just beginning to qualify as TAE. TAE would be exolife that is sufficiently advanced to travel to other solar systems and leave evidence along the way. So our galaxy may have plenty of intelligent life at or below our technological stage that has yet to produce sufficient outreach for us to detect it. In the ~13 billion years of existence, the Milky Way might have produced many forms of intelligent life that (for one reason or another) failed to survive to a mature TAE that could explore the galaxy and leave evidence.

The lack of evidence in our own galaxy is certainly an indication that TAE is uncommon. But it does not, in any way, suggest that TAE did not or does not exist and certainly says nothing about the existence of intelligent life less advanced than TAE.

Bottom line, nobody knows if we are alone in the universe. But if we are, we are 1 in ~6 trillion.

No argument from me concerning what you posted but it should be noted that it doesn't really address what I was talking about concerning the claim that, "statistically, there is no doubt it (intelligent life) exists".

Further, it should also be noted that estimations of habitable planets are almost certainly based on pretty generous assumptions. I would expect the number to go down significantly as our ability to study exoplanets matures. For instance, I read an article not long ago that says they are finding gas giants much closer to their star (or stars) than was generally accepted to be likely and is suprisingly common. Even in the Goldilocks zone. If I remember correctly, this apparently decreases the likelihood of an Earth type planet in the same zone from developing life.

Also, it is thought that life on our planet may not have developed if we did not have the moon we have. Other criteria may involve the tilt of the planet, does it have a magnetosphere and so on. This is why it bothers me when people say it is statistically likely. We do not have the data to make such a claim. Instead, it seems more a statement of incredulity than a statement of fact.

That said, I don't wish to appear to be against the idea there is other life out there. I'm not. My position is either there is or there isn't. However, I also recognize the possibility that we may be it. We won't know until we find it, or don't.

I purposely avoided the statistics dimension to focus on the question of life and avoid an unnecessary debate on what constitutes statistics and the various statistical models one could offer.

On the flip side, there might be all sorts of exotic life that survives outside of the Goldilocks zone. If we someday discover silicon-based life, for example, would we dismiss it as non-life? (I would not.)

There are no doubt all sorts of conditions that we have not discovered in the ~6 trillion habitable planets. And if we do not limit ourselves to carbon-based life with which we are familiar how many other planets might host life? There are ~1 sextillion stars in the universe so at 1 planet per star the potential landscape is staggering.

True, no way to know for sure until we find evidence. However, given the number of potential hosts, I would be quite surprised if we were alone in the universe.

Depends on what we're examining as a possible life form, in my opinion. A difficult bar to meet since, the last I looked, there seems to be some debate as to what qualifies as life here on Earth. Personally, I think it probably is a case of "I know it when I see it."

True, but one probably would do better not to try to include something exotic such as silicon life forms as trying to detect the life we know and understand (more or less) is proving difficult enough. Just my opinion.

I, personally, don't know whether I'd be surprised or not. Sometimes I think it would be hard to believe we are the only ones. At the same time, I don't have any problem with the possible fact that we are the only ones. To the best of my knowledge, there isn't anything that says there has to be life at all. For instance, with all the possibility you suggest, one could claim that some creature on some exoplanet would fulfill the requirements of being a unicorn. If life populates the universe to the extent some suggest, then the existence of a unicorn is pretty good. Even so, there's nothing I know of that states unicorns must exist.

I was thinking of a creature that can consume fuel, produce waste and reproduce. That gives an exo-plant. If the creature is mobile it is an exo-animal. If it can reason, it is an exo-intelligence. Even if it is made of Silicon instead of Carbon and can survive conditions that would kill any life form we know.

I am just saying that an exotic life form would, to me, be a life form. If we discovered a reasoning life form that had nothing in common with our biology I would have a hard time holding to the notion that we are alone in the universe.

There is a very big difference between hypothesizing the existence of a specific thing (e.g. a unicorn) vs. hypothesizing the existence of life in general.

No argument. I was simply suggesting that detecting the kind of life we know about is sufficiently difficult all by itself. I'm not sure that attempting to detect, purposefully, radically different life forms is advisable.

True, but not the point I was making. Rather, it was that life in general was no more likely than the existence of unicorns. I state this because of the false idea that, because life exists on planet, it necessarily exists on others. The only scientifically supportable conclusion that can be reached is that life exists on this planet. There is not scientifically supportable conclusion that life must exist elsewhere. Hence the unicorn example. They may exist but there is nothing we know of that demands that they do.

And the fact that there is one, means there is more than likely a lot more. If there is any truth at all to the Drake Equation, (which is based on only our galaxy), there should be thousands of sentient species other than us.

Where:

N = The number of civilizations in the Milky Way Galaxy whose electromagnetic emissions are detectable.

R * = The rate of formation of stars suitable for the development of intelligent life.

f p = The fraction of those stars with planetary systems.

n e = The number of planets, per solar system, with an environment suitable for life.

f l = The fraction of suitable planets on which life actually appears.

f i = The fraction of life bearing planets on which intelligent life emerges.

f c = The fraction of civilizations that develop a technology that releases detectable signs of their existence into space.

L = The length of time such civilizations release detectable signals into space.

.......

We tend to base how we view life based on how long the Earth has been in existence, ~4.5 billion years. But the universe has been around, (as far as we know), at least 13 billion years. That means the universe was around for 8.5 billion years before the Earth even formed, (I know, that's some seriously fuzzy math).

That's a lot of time for other civilizations to rise and fall.

Let's also consider Mars. It's a tad off the mark for human life, but honestly, not by much. So one habitable, and one almost habitable, in the same solar system.

The real problem is that we have only been putting out any signal strength that could actually leave the Earth for what...60? 65 years? That's a bubble around the Earth going out to about 60 light years, which even on a galactic scale is almost literally nothing.

I am certain, just based on numbers alone, that it would be almost impossible for there not to be hundreds if not thousands of sentient species in our own galaxy.

Of course, that's just my opinion.

Life in general is absolutely more likely than a very specific hypothesized life. Unless you can somehow attach a likelihood of zero, the fact that life in general can be any of N things (especially where M of those N things are already known to exist) it is clearly more likely than a specific, merely hypothetical life form.

I missed someone claiming necessarily (likely, was claimed). I agree that the fact that life exists on Earth only means that life is possible; it does not mean that life necessarily exists elsewhere.

True. We can't even achieve 10% the speed of light, which would get us to the nearest star in what...50ish years? Not even remotely fast enough. The fastest space vehicle man has ever made is Voyager 1. 38,610 MPH. In 75,000 years, it will pass Alpha Centauri, 4.1 light years away.

At the end of the day, space is incredibly vast and we cannot go nearly fast enough to even get to the nearest star in a lifetime.

Well, to be fair, we could get to the end of the solar system and back, but it would be a bloody long trip and....well, no wi-fi. There could be hundreds or thousands or even millions of species out there that are FAR more advanced than we are, we just haven't come across them yet.

Indeed and maybe that's why they haven't pulled over to talk to us. We have nothing to offer them.

I found a video a while back, it's called Riding The Light. It shows what the sun, (Sol), would look like if you were to speed away from it at the speed of light. It really puts into perspective how vast even our own solar system is...

That is a statement I have a problem with. There's no basis for it. That is, not that any particular type of life is more likely but, rather, that any sort of life is more likely than not simply because it exists here. It may be that one cannot swing a cat without hitting some sort of life in this universe. It may also be that life is so rare that, should other universes exist, it would take millions of them to produce another chance occurrence of life elsewhere. Point being, we simply don't have the data.

Saying there must be other life out there, regardless of it's type, is pure speculation and not science. There is nothing wrong with speculating. There is something wrong with trying to pass it off as science.

The Drake equation was not a serious attempt and determining how many other advanced civilizations may be out there. It was an exercise in determining what questions need to be asked concerning examining the universe for other advanced life. Put another way, Drake wasn't trying to actually estimate the number of advanced civilizations out there but, rather, trying to get people to begin thinking about what questions to ask concerning the issue. What is it we need to look for in order to find advanced civilizations?

You misunderstood what I wrote.

I compared a single, specific hypothesized life (your unicorn example) to any form of life. I compared 1 to N. So let's assume that the probability that exolife exists (p) is greater than 0.0. Even if p=0.0001 the mathematics is obvious: 0.0001 * N > 0.0001 * 1.

In simple language:

N > 1

I did not write that. I have never claimed that there must be other life out there.

Show me where I have passed off speculation as science.

Yes but on a planet like earth the rate at which one cell organisms are born and die means the Lottery has trillions of drawings per millisecond. Even in complex creatures like ourselves every child conceived is an opportunity for a genetic mutation that improves the species. Any genetic mutation that gives an advantage will allow that individual a higher likelihood of surviving and breeding and through natural selection eventually that genetic mutation becomes the normal genetics of the species. Given millions or even billions of years the development of higher intelligence becomes pretty likely.

The smarter the beast, the more likely to survive and procreate.

And yet, we're the only example of it on this entire planet, which is chock full of life. It absolutely flourishes here.

If it were indeed likely, then there should be more than one example of it on Earth. There's not. Out of all the billions of species this planet has produced, we're the only one.

As if we'd allow another intelligent lifeform to share this world. The benchmark we call intelligent life is really just an accumulation of knowledge and technology. 50,000 years ago we were nearly as intelligent as we are now, we had the capacity but we lacked the knowledge so we lived like packs of wolves. There are many animals today that live in complex family groups and have simple language, they have intelligence, Who's to say they couldn't make the leap to where we were 50-100,000 years ago, they've already evolved 98% of the way another 2% hardly seems impossible, in fact it seems probable. Given human nature (which just might be the nature of higher intelligence) we are unlikely to tolerate any species with intelligence approaching out own, certainly if they competed with us for resources.

You need to look around more, or provide details for your definition of " higher intelligence".

Many species have communication.

DO ANIMALS 'TALK' TO EACH OTHER? YES, AND THEY TAKE TURNS JUST LIKE HUMANS

Several species have tool using capabilities.

10 Animals That Use Tools

Many many species are intelligent for training.

Positive Reinforcement Training for Sharks, Alligators and More

It's more than that. It's also biological machinery. Most importantly, large inquisitive brains with lots of memory that can not only investigate the world around it and discover complex ways of manipulating nature to its own advantage, but can also develop and remember a complex language with several thousand word meanings to facilitate the transmission of what has been discovered to the next generation. Also, bipedalism to free up limbs, at least among land animals, and prehensile digits at the end of those limbs with the dexterity to tinker and carefully manipulate the world around them.

Our closest relatives, the other great apes, are the only creatures that even come close, and they still fall short.

I don't know what's supposed to make it seem probable, but I'll agree it's possible. The postulate that advanced, technological life is exceptionally rare in nature (and at present singularly unique to humans) still stands, though.

What in the world makes you say that? If a population of chimpanzees or bonobos somewhere starts using fire and making complex flaked stone tools or something, I can imagine every wildlife biologist and nature conservatory in the world lining up to protect them even more fiercely than they already do. They'd probably even try to show them how to do some basic agriculture, or how to weave natural fibers into useful items like baskets or something, just to see if they could do it. It would be a mind blowing development. The last thing we'd be trying to do is harm them. That kind of ability is unheard in nature aside from us. That's my point.

Gotta say, I find it hard to believe that you don't know what I'm talking about.

My post to zuksam might help you out.

The entire history of mankind ! These days they would try to protect them but that attitude has only been around about 50 years and they might be successful as long as it was just one group and populations stayed very small. Humans aren't very tolerant and they don't like to share so all it would take is one violent encounter between man and these apes and the local humans would kill them all.

To say that humans are the only intelligent life form in existence, and that is definitely questionable, given the size of the universe along with the sheer number of stars and planets out there it is the ultimate expression of arrogance and vanity. There is also the Drake Equation to take into account.

Not only do I believe there is intelligent life out there, I believe the technology they possess makes us look like scientific beginners.

Well, there has been some pretty astonishing evidence of UFOs lately. Pentagon verified, no less. I even had what could only be described as a UFO sighting myself this past summer. First time in my entire life.

If they really are out there, they could be millions or even billions of years ahead of us, which is intriguing and terrifying all at the same time.

What makes you think Homo sapiens is intelligent? Dinosaurs roamed the face of the earth for 100 of millions of years. Mankind a couple hundred thousand...

Intelligent? Maybe, but ahead of us? Just how long did it take for us to evolve to where we are and how many steps it took, is the universe old enough to allow life elsewhere to evolve past us? If so I don't believe that they would be too far ahead of us.

They may have done it faster than us. Just because it took us this long does not mean that others did also.

Our solar system is what, about 4 billion years old, and as pointed out by TiG it took 1 billion to get us to here, now say we go to Mars and find that there is life there, it may be even be older then life on earth, but odds are it will still be just microbial. So going by Mars life evolved to intelligent, on earth, in a flash. 1 billion years is pretty dang quick, another planet doing the same IMO is not very likely.

From the article:

Let me toss in a couple of points not considered here....

One of the primary causes of mutation in all lifeforms on this planet comes from radiation. Our planet is bathed in it. A fair number of the mutations are detrimental to the viability of the lifeform, and they die. Cancer can be considered a type of cell mutation, again some of it from radiation. But in some rare cases, that mutation becomes beneficial, and makes the improved lifeform more robust. Now imagine a series of planets where complex cells formed 2.7 billion years ago like they did here on Earth, but were subjected to a higher level of radiation induced mutations. Given that time frame, it would be easy to imagine an accelerated evolutionary time scale for development.

Second point to make. How do we know what life is?

We as a species are still too limited in our thinking to really understand what we are trying to study. The book "The Andromeda Strain" impacted me early in my teens when I first read it. There, one of the examples made was of the difficulty trying to study life that may be so different than we are that we can't recognize it. There, one of the scientists tossed out the idea that "rocks are alive". Given that their life-spans are a billion years, how can we possibly study something that moves so slowly that we can't even measure it's movement. Consequently, if rocks are living, how could they study us in reverse?

In another Michael Crichton writing, an alien visitor arrives and finds a functioning refrigerator, which is taking energy in, and converting it to regulate it's internal temperature. These are two of the possible definitions of life... conversion of energy, and internal regulation. The alien visitor ignores the bag of corn seed next to the refrigerator as it seems inert and non-reactive, thus not a form of life. We though from our perspective know the exact opposite to be true.

Even the ability to reproduce itself is not without confliction. Viruses and not considered by science to be "alive", but most definitely have the ability to replicate the hell out of themselves now don't they.....!

NASA is still having a hard time determining what life is.

All good mental exercise, and a welcomed break from the cement heads that want to take us back in time, or at the very least, stop the masses from thinking too much. Great seed.....KUDOS!

It should have happened billions of years before that, if life is indeed common, that is. Furthermore, if advanced technological life really is a likely result of evolution, then evidence of them should be all over the galaxy by now. Kind of like how we find seashells all over the entire planet, even in half-billion year old rock. Once biomineralization evolved and made exoskeletons possible, it apparently increased survivability dramatically and allowed mollusks to thrive and spread to every end of the Earth, leaving all kinds of shell evidence of their presence behind them.

My hypothesis is that once a species develops a level of technology that allows them to break the chains that tie them to their home world, they should do exactly what the mollusks did: reproduce, multiply, and slowly spread everywhere, leaving plenty of evidence of their activity behind them. But I'm talking about technological evidence instead of biological evidence like the mollusk shells. Namely, engineered structures in orbit of various planets and asteroids, even way down here by the inner planets where solar radiation is strong and freely available for plentiful energy.

My conclusion is that because we see absolutely nothing in space, right here in our own vicinity, where it should last pretty much forever and not deteriorate or decompose - no structure, no remains at all, no metaphorical half-billion year old mollusk shells - then given the age of the galaxy, it means that life like that is in fact not likely or common. If it was, we'd see evidence after so many billions of years.

What do you think? Sound crazy?

I think it's safe to say that when people think about how successful life is here, and how early in Earth's development it seems to have started, then when they wonder about life elsewhere they are thinking about biochemical life just like we have here. Naturally-occurring amino acids forming proteins that are turned into tissues by RNA, with the instructions being stored in DNA or something very similar. The idea is that if it happened here so early on, then maybe it's common throughout the universe. It's perfectly reasonable assumption, if you ask me (for simple life, that is).

So, as long as we're talking about life like that, then we should certainly be able to recognize it if we ever see it. It's the only kind we really know to exist.

If some other kind of life is out there, then yeah, we might not even recognize it.

It's a big universe DS.... and for all we know FTL space travel is impossible.

Best way I can put it is that I can't confirm nor deny the existence of other life in the universe/s based upon the evidence to date and my scientific training.

Now you want to take bets based on statistics..... Yes there is other life out there, but overcoming the FTL barrier just might have prevented that other life from making its way to our solar system.

Ah, but they wouldn't need FTL. At 10% of the speed of light the galaxy could be spanned in 1 million years. 5% would take 2 million. 1% would take 10.

The galaxy itself is much older than the Earth and the rest of our solar system, so if advanced, technological life like us really is likely in nature, then several species should have emerged and become space faring billions of years before us. Even at relatively low speeds they should have been able to multiply and spread everywhere in the galaxy given the time available, except for maybe the higher energy middle. They could have done it many times over, actually. The galaxy should be downright crowded by now. They should even be here in our solar system. After so many billions of years, physical evidence of them should be plentiful and detectable right here in our own immediate neighborhood, the kind of structure we could see and track with radar. It doesn't seem to be present, though, so it may be that species like us aren't very likely at all. We really might be alone, at least in this galaxy.

Yes, even if they are billions (for that matter even thousands) of years ahead of us they should have easily been able to detect us, even the life before us. I am sure that they would've already been here and wouldn't be following a prime-directive.

Just had a thought, maybe instead of them doing all the heavy lifting of mining and accumulating the minerals and metals of this planet, they'll just let us do it and then come and take it when they need it. (Maybe George Carlin was right, but it is the universe that needs plastic).

The Earth formed roughly 8.5 billion years after the birth of the universe. That's a lot of time for another species to rise and fall.

Lol based on current evidence intelligent life evolves 100% of the time on an earth sized rocky planet orbiting in the goldilocks zone around a medium yellow star

Life itself is a profound mystery. It seems as though life (at least our view of life) is rare to emerge but once it does (in the right conditions) it defies the odds. Life on our planet has survived extraordinary dynamic conditions largely due to its ability to evolve (and thus indirectly adapt) to its environment.

The universe is vast; it is highly likely conditions favoring life exist and that life has emerged elsewhere. The problem is that the universe is also extremely sparse. With all of our technology we see only the tiniest fraction. Signs of intelligent life, if emitted, must survive time and space before we even have the chance to detect.

Life may be throughout our universe but out of our range to detect it. In short, the lack of evidence of intelligent life elsewhere is no surprise, but that absence of evidence is certainly not evidence of absence.

As long as there are wars, terrorism, murder, people who believe the Earth is only 6000 years old, it's pretty clear to me that Humans have a lot more evolving to do before they can call themselves "intelligent life" - any bets on how many more million years are needed?

any bets on how many more million years are needed?

Nah.…. I hate to lose my money.

LOL. Well, we are supposed to all be part of civilization, but one might question just how civilized we are yet. I'd say we have a way to go.

Long...… looooonnnnnngggg…….. way to go Buzz.

Hell, I'd be happy if everyone could just do long division with a pencil and paper.

Or how about that the line between the numerator and denominator of a fraction means.... divide!!!! Is this asking too much?