The Meaning and Origin of ‘For Whom the Bell Tolls; It Tolls for Thee’

The Meaning and Origin of ‘For Whom the Bell Tolls; It Tolls for Thee’

In this week’s Dispatches from The Secret Library , Dr Oliver Tearle analyses the origins of a famous phrase about human sympathy and mortality.

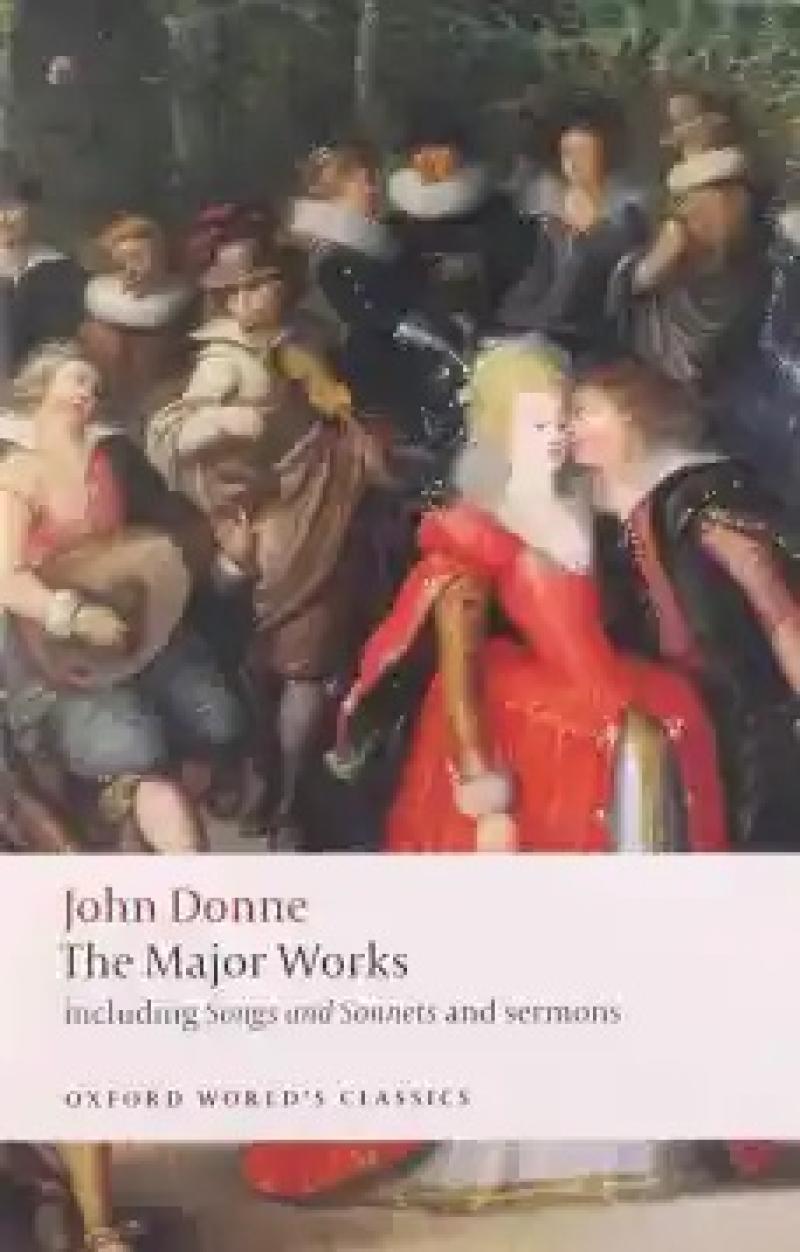

'Never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.’ This phrase has become world-famous but its origins, and even its meaning, are often misconstrued or at least only partially grasped. Many people would be able to identify the origins of ‘never send to know for whom the bell tolls’ in the work of John Donne (which would be correct), with quite a few of them thinking that the line originated in a poem of Donne’s (which would not be correct).

‘Never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee’ is a phrase from one of John Donne’s most famous pieces of writing, but it’s not a work of poetry. Instead, this line appears in one of Donne’s prose writings:

No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main; if a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or of thine own were; any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

John Donne (1572-1631) was a hugely important figure in Elizabethan and Jacobean literature: in some ways, he is second only to Shakespeare in his literary importance. As a young man in the 1590s, he had pioneered what would become known as metaphysical poetry , writing impassioned and sensual poetry that drew on new debates and discoveries in astronomy for its imagery and poetic conceits . I have selected and discussed some of his finest poems in an earlier post .

But Donne left behind his heady and headstrong youth and eventually rose high in the ranks of the Church of England (despite being part of a recusant Catholic family), and became a devoted Anglican. In time, he was appointed Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral. He would write a series of Holy Sonnets which are as passionate as his youthful love poems, but this time God, rather than a mortal woman, is the subject and addressee.

Donne was writing at a time when the English language was, in many ways, at its most supple and inventive. This was the great age not just of the Elizabethan and Jacobean drama, of Shakespeare and Marlowe, but also the King James Bible (published in 1611) and the sermons of Lancelot Andrewes. Donne himself was also a powerful writer and deliverer of sermons, and a talented prose writer.

The famous lines he wrote that contain the ‘never send for whom the bell tolls’ statement were written in the last decade of his life. In 1623, he fell ill with a fever and, while he recovered, he wrote the Devotions upon Emergent Occasions , a series of prose writings split into three parts: ‘Meditations’, ‘Expostulations to God’, and ‘Prayers’.

The oft-quoted ‘no man is an island’ line, as well as the ‘for whom the bell tolls’ one, come the seventeenth Meditation in Donne’s Devotions . Donne was gravely ill and his own death, and the mortality of all human life, must have been continually on his mind; the Devotions come back to sin and salvation time and again, as in the Holy Sonnets.

The meaning of ‘never send to know for whom the bell tolls’ is fairly straightforward. We should feel a sense of belonging to the whole of the human race, and should feel a sense of loss at every death, because it has taken something away from mankind. The other famous phrase from this Meditation that has entered common usage is ‘no man is an island’, because no individual can subsist alone.

We need not only social company and companionship, but also an awareness of how we all have a share in the world: we are all part of the human race and the suffering and passing of another human being should affect us, not least because it is a regular reminder that one day, it will be us for whom the funeral bell is tolling.

The funeral bell that tolls for another person’s death, then, also tolls for us, in a sense, because it marks the death of a part of us, but also because it is a memento mori , a reminder that we ourselves will die one day. Ernest Hemingway’s great novel about the Spanish Civil War was named For Whom the Bell Tolls after Donne’s line, not just because death pervades the protagonist Robert Jordan’s thoughts but because Spain’s fate will affect everyone. George Orwell, whose political writing was changed forever as a result of fighting in the Spanish Civil War, would doubtless agree.

Oliver Tearle is the author of The Secret Library: A Book-Lovers’ Journey Through Curiosities of History , available now from Michael O’Mara Books, and The Tesserae , a long poem about the events of 2020.

While I was majoring in university in English Literature, we studied John Donne's Meditation XVII, which is the topic of this article. The article, John Donne's Meditation XVII, Hemingway and his novel and the movie adapted from it both named "For Whom The Bell Tolls" all combined has a special meaning to me.

Ernest Hemingway in Spain

It was the combination of his time in Spain and his knowledge of Donne's Meditation XVII that led to his authoring his novel "For Whom the Bell Tolls" which was adapted into a movie named the same starring Gary Cooper and Ingrid Bergman. Hemingway applied the lesson of that piece of literature in his novel "For Whom The Bell Tolls". The American Cooper's presence in Spain fighting with the loyalists indicates that they were all in that war together. That was all of special interest to me because my mother's brother joined the International Brigade that fought the fascist Franco's army.

My opinion of the meaning of the phrase ‘Never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee’ was a little different than that of the author herein, because I was following the meaning of the rest of the Meditation in that we are all attached in some way to each other. Back at the time Donne wrote it there were no newspapers or other means of communication so when the bell of a village church was rung it was to announce the death of a local person, causing all the people to go to the church to find out who had died. However, Donne was saying that we all died a little when that person died - i.e. it tolls for all of us, so there was no need to go find out who it was.

Perhaps there is a member or two of NT who is interested in discussing this because in a way it could also be adapted to politics.

And here I thought it was a Mettalica song...

Or a Bee Gees song? I'll stick with Donne's original meaning and Hemingway's adaptation of it. At the end of the movie Cooper stayed behind to hold off the approaching enemy, was sure to be killed, and he told Bergman to go because where she goes he will go as well because of their love they were attached, a part of each other, which is the "No man is an island, but is a part of the main" concept - that we are all a part of each other. I don't see that in the music lyrics.

I'm going to go to sleep now. I really hope that when I wake up in the morning I'll discover that there are more NT members than Ender who have an interest in literature.

Okay, that hope was unfulfilled. That will teach me to post an educational article about English Literature on NT. Okay, I'll try to focus mostly on movies and Creative Arts.