Maternity care deserts are growing in the U.S., March of Dimes report finds : NPR

October 12, 20229:37 AM ET

Rachel Treisman

Twitter  Enlarge this image

Enlarge this image

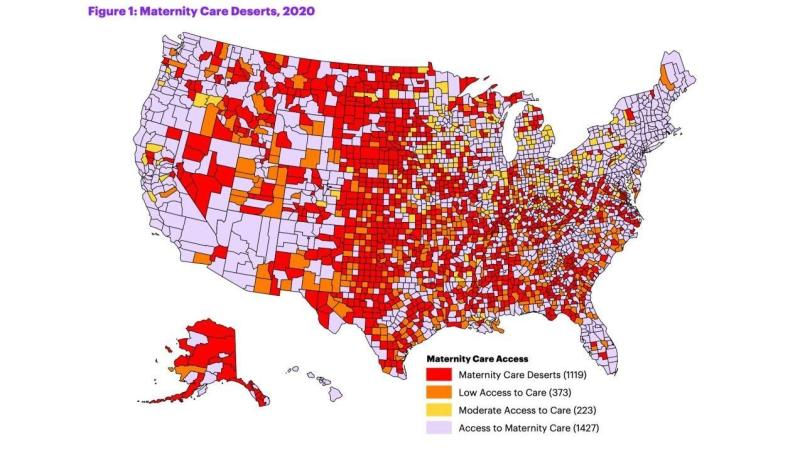

This map from the nonprofit March of Dimes shows maternity care deserts across the U.S. in 2020. March of Dimes/US Health Resources and Services Administration.

March of Dimes/US Health Resources and Services Administration.

Access to maternity care is decreasing in the parts of the U.S. that need it the most, affecting nearly 7 million women of childbearing age and some 500,000 babies.

That's according to a report released Tuesday by March of Dimes, a nonprofit focused on maternal and infant health. It finds that 36% of counties nationwide — largely in the Midwest and South — constitute "maternity care deserts," meaning they have no obstetric hospitals or birth centers and no obstetric providers.

It paints a slightly grimmer picture than the organization's last such report, which was released in 2020. Five percent of counties have a worse designation this time around, and there's been a 2% increase in counties classified as maternity care deserts — accounting for some 15,933 women living in more than 1,000 counties.

March of Dimes says these changes are driven primarily by the loss of obstetric providers and hospital services within counties, as a result of financial and logistical challenges including the COVID pandemic.

And it warns the result is disproportionately harming rural communities and people of color: One in 4 Native American babies, and 1 in 6 Black babies, were born in areas with limited or no access to maternity care services.

Mothers and babies in maternal care deserts face a higher risk of poor health outcomes, including death. Roughly 900 women died of pregnancy-related causes in the U.S. in 2020, the report says, adding that nearly two-thirds of such deaths are preventable.

Enlarge this image

Enlarge this image

A midwife at Sisters in Birth, a Jackson, Miss., clinic that serves pregnant women, uses a hand-held doppler probe on a patient from Yazoo City to measure the heartbeat of her fetus in 2021. Rogelio V. Solis/AP hide caption

Rogelio V. Solis/AP

The data for the study — and the concerns it raises — predate the Supreme Court's decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, says Dr. Zsakeba Henderson, March of Dimes' senior vice president and interim chief medical and health officer. She says there isn't enough data yet to show the impact of Dobbs , but acknowledges there is a known relationship between abortion restrictions and access to maternity care.

Henderson tells NPR in a phone interview that the report highlights the scope of a worsening problem in the U.S. — and that specific policy changes could help.

"Many people don't know that we are in a maternal and infant health crisis in our country. Our country is currently the least safe to give birth and be born in among industrialized countries, and ... part of that problem is not having access to high-quality maternity care," she says. "We have failed moms and babies too long in our country, and we need to act now to improve this crisis."

Rural areas are the hardest-hit

The number of obstetric providers (meaning obstetricians and certified midwives) in the U.S. actually increased — by 1.7% — between the 2020 and 2022 reports, Henderson says. But only about 7% of providers serve rural areas.

Two in 3 maternity care deserts are in rural counties, the report says.

"Doctors choose to practice, often, where they want to live, and a majority of obstetric providers are in urban areas," she explains, adding that fewer providers are now available in certain areas largely because hospitals have closed maternity wards, primarily for financial reasons.

Some areas did see improvements in access to maternity care during this period. For example, hospitals expanding obstetric services actually increased access to care in eight counties (compared to 37 counties that experienced the opposite).

Florida had the most women impacted by improvements to maternity care access, while Ohio had the most impacted by overall reductions in access to care, according to data in the report. Nationwide, more than 2.8 million women and nearly 160,000 babies were impacted by reduced access to maternity care.

The report underscores the need to improve access to maternity care — and high-quality care, at that. For example, Henderson says, people with high-risk pregnancies need access to high-risk care.

"It's one issue to have maternity care deserts and not have anyone to provide care," she says. "It's a whole other issue having someone that can provide the highest level of care that is needed."

What to know if you're in a maternity care desert

There are some resources available to women living in maternity care deserts.

Henderson says other providers can help supplement and improve access to maternity care, including those that serve in Federally Qualified Health Centers and doctors who practice family medicine.

They can be a great source of help to people who can't see an obstetrician, especially when it comes to prenatal and postpartum care, she explains. Midwives and doulas are also sources of support that have been associated with improved maternal and infant health outcomes.

"We also know that improving the social and economic conditions and quality of healthcare at all stages of a woman's life will help mitigate some of the issues of access to maternity care, because how healthy a woman is before pregnancy impacts how well she does and what complications she may have and the health of that baby from that pregnancy," Henderson says.

Another option is accessing maternity care remotely via telehealth — at least in theory.

"One of the things we realized is that in order to have access to telehealth, you need to have access to broadband internet," Henderson explains.

This latest version of the report is the first to examine the distribution of broadband access across the country and its impact on telehealth. Among its findings: Counties with low access to telehealth were 30 percent more likely to be maternity care deserts.

More than 600 U.S. counties were designated as having "low telehealth access" in 2020. March of Dimes says that "suggests that there are geographic regions of the U.S. that may have limited access to acceptable broadband, reducing the reach of telehealth for those who may benefit from its use the most."

That's just one of the issues the organization is lobbying to change in its efforts to improve access to care.

Broader policy changes are needed, advocates say

No single solution will fix maternity care deserts, the report says. Instead, it offers nearly a dozen suggested policy changes that would tackle the issue from different angles.

"While this is an ongoing problem. there are potential solutions that we know exist to help address these issues," Henderson says.

Those include making health insurance more accessible by states expanding Medicaid to cover individuals who fall at or below 138% of the federal poverty level and raising income eligibility thresholds for parents. (Medicaid covers nearly half of births in maternity care deserts, a higher percentage than in areas with full access to care, the report notes).

With Black Women At Highest Risk of Maternal Death, Some States Extending Medicaid

The organization also wants states to extend the Medicaid postpartum coverage period from 60 days to 12 months, an option made available to them by the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021. Two dozen states and Washington, D.C., have done this as of August, and the report urges Congress to make that extended coverage period both mandatory and permanent under all state Medicaid programs.

When it comes to actually getting preventive and supportive care, March of Dimes says much can be done to make the services of doulas and midwives more accessible to people who need it.

Henderson says that many of the countries with better pregnancy outcomes have a large midwifery workforce, whereas only about 10% of pregnancies are managed by midwives in the U.S. Doulas don't provide that kind of clinical care, but offer information as well as pregnancy, labor and postpartum support that can improve birth outcomes.

Family

"We know that the midwifery model results in improved outcomes and less [risky, unnecessary medical] intervention, and we also know that doula support helps prevent [poor] outcomes and helps get moms to the help that they need faster," Henderson says.

Currently, the people who access doula care are only the people who can afford it, Henderson explains, because it's not typically covered by insurance.

March of Dimes is pushing to expand equitable access to doula services in two main ways: training and developing the workforce, and reimbursing the cost of their services. As of August, only five states were actively reimbursing doula services on Medicaid plans, the report says, and another seven were working to implement that change.

The organization says it will continue to push for policies at the state and federal level that will "increase access to make this nation a better place to experience pregnancy and give birth," and it hopes this report will serve as a catalyst to bring about those changes.

Tags

Who is online

384 visitors

Just shows why the US is at the top when it comes to maternal deaths.

I disagree with this. We saw during the first years of COVID where hospitals were refusing all discretionary services to focus on COVID, and the government was paying for the services thru the Medicare / Medicaid rates. Hospitals were closing floors and laying off staff because the Medicare/Medicaid rates are too low to support the hospital. We also saw a lot of rural hospitals close their doors because they could not afford to keep them open. Expanding the coverage of Medicaid to cover more people will provide insurance coverage for these people but it does nothing to guarantee there is a facility they can go do.

Instead I think they need to expand the Indian Health Services to include non-reservation rural areas that are underserved by the medical community. I think they should take a page from Englands National Health Services and the federal government needs to open hospitals with federal employees including doctors and nurses. In order to control the system you have to also control the costs and you cannot do that if you are only managing the payment side. People for years have been pushing for a Medicaid for All approach, this could be the start of such a system. It's going to be expensive at first because you basically have to keep the existing system up and running while you are building up the new system but eventually the old system can be gracefully shut down.

Perhaps those rates should be addressed.

Perhaps, but taxes would need to go up and other spending needs to be controlled better as we already spend a lot of money on these two programs each year.

Medicare spending for 2021 was $875B, Medicaid spending for 2021 was $728B.

IMO just adjusting rates would not solve the underlying problem of costs. Similar to the student loan forgiveness plan, it would only work on one side of the equation. To make any real impact they need to work on both sides of the issue or there is no incentive for healthcare providers to control costs.

IHS is short of staff including doctors and nurses and is underfunded and has been for decades. There is no way that they could handle any influx of patients. I do not use IHS just for that reason since I do have other medical coverage I don't want to take away from an Indian that has to depend on IHS as their only provider,

Rural hospital and maternity facilities are really lacking in rural areas and the number that has closed in the last few years is making an already bad situation much worse.

Yes, it would need a huge expansion to take this on. I suggested it as it's an existing service that has the knowledge of how to go into a rural area and set up healthcare. The other existing federal agency that has the knowledge is the VA but they really don't have the knowledge on how to set up and work in a rural area, they tend to go towards the major metropolitan areas. It just made sense to me to expand an existing bureaucracy rather than waste the money and resources to set up a new bureaucracy. And who knows, maybe while they are building up the agency they could help improve the existing services to provide more staff where it's needed? To me that's a win-win.

But I wouldn't expect them to do that as Washington has not shown themselves willing to actually fix problems around health care.

As I stated earlier the funding has been lacking to say the least. There aren't enough IHS facilities to handle the current load of patients. The one thing that I had forgotten is that in 2019 IHS closed a birthing center at the IHS hospital in the Phoenix area with no notice saying that he was temporary, it's 2022 and it is still closed to my knowledge.

I understand what your proposing but if past performance is any indicator of future performance it has a very long way to go and, IMO, would fold under the lack of funding and personal.

It's pretty sad that we are one of the richest countries, yet we have such poor natal care. It just blows my mind that this country doesn't value actual people who want children while pretending to care so much about unwanted pregnancies.

Our local hospital closed its labor and delivery department years ago. If you're having a baby, you're going one county north or one county south. From my house, it's 40 miles to the hospital north of us, and about 50 miles to the hospital south. For a woman with a high-risk pregnancy, that's a long way.

If a woman does give birth in our local hospital, it will be because she couldn't make it to one of the other hospitals, and her delivery will take place in the emergency room. Not an ideal setting, and not with personnel who specialize in obstetrics.

[deleted]

There are a lot of issues around this. Last night I remembered reading an article years ago that talked about how new doctors and nurses were not going into labor & delivery practices due to the rising costs of insurance. Tort laws around the time would allow parents to sue the doctors and nurses for any problem that could be tied back to a birthing issue, and the time to sue could be anywhere in the first 18 years of life of the child. At the time, if I remember the article correctly, liability insurance rates were only second to anesthesiologists.

Additionally in a lot of areas in the past years a lot of expectant mothers were covered under Medicaid. The re-imbursement rates are low so that hospitals actually lost money.

That is definitely a huge issue. I had an obstetrician as a patient who was new to town. He left his last practice because his malpractice premiums were $10,000 per month. He said he'd never had a malpractice suit against him. That's not sustainable.

Perhaps not but lawyers make good campaign donations to Dems. When PPACA (Obamacare) was being drafted, Congress held several hearings medical tort reform. These items were left out of the final bill, and ACA did nothing to limit medical malpractice liability.

That map reminds of something.

Some sort of political map...

I've been saying all this for years when the abortion issue was raised. Minnesota Public Radio had a multi-part article on the subject last year. The politicians don't give a shit about rural medical care and healthcare facilities are profit driven.

Our big local provider closed almost all there more rural clinics and is now trying to create a huge medical campus here. They bought out another smaller regional provider where I suspect they will start closing less financially viable facilities as early as next year.