'The Cause' Review: Revolutionary Answers

By: Kathleen DuVal (WSJ)

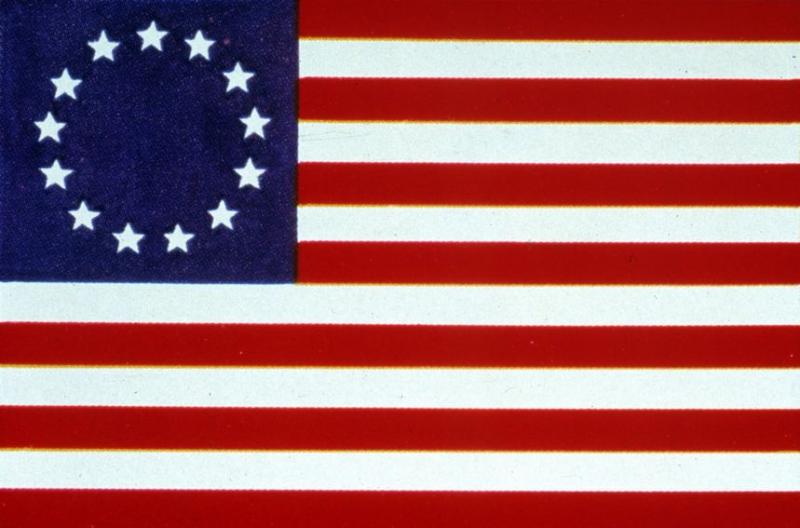

In the summer of 1976, my family took a hot car trip in our Chevy Impala from our home in the middle of the country to be part of the bicentennial. I remember that visiting Philadelphia and colonial Williamsburg in Virginia made being an American feel tangible—a proud if vague connection to tri-cornered hats, seas of Betsy Ross flags and the spirit of '76. The 250th anniversary of the founding of the United States is coming up in 2026, and now, no less than in 1976, the country could use reminders of how difficult and important becoming a democracy was. The U.S. Semiquincentennial Commission, commissioned by Congress to commemorate the upcoming anniversary, has the mission "to catalyze a more perfect union by designing and leading the most comprehensive and inclusive celebration in our country's history." This seems like an appropriate time to read a good overview of the American Revolution, as a lesson in what happened and why it mattered.

Unfortunately, Joseph J. Ellis’s “The Cause” is not that book.

Mr. Ellis does cover the basics of the Revolution. The British Parliament imposes new taxes, colonists protest, tea is dumped, congresses meet, shots are fired, independence is declared, more shots are fired, winters are weathered, and a treaty is signed. The title aptly reflects how the revolutionaries drew supporters to a glorious cause without necessarily specifying its parameters. Artisans and laborers taking to the streets of Philadelphia did not want exactly the same revolution as wealthy merchants and planters did. Some ambiguity as to ends and means can make leading a coalition into revolution a little easier.

When King George III declares the colonies to be in a state of rebellion and appoints as Secretary of the American Colonies hard-liner George Germain, who had called the colonists “overindulged children,” Mr. Ellis ably conveys diverse reactions. Bostonian John Adams felt confirmed in his assumption that compromise was impossible. New Yorker John Jay recalled surprise among many of his friends—a common feeling of being slapped in the face like a naughty child. Pennsylvanian John Dickinson was filled with dread.

Yet, for most of its pages, “The Cause” is written in the ponderous self-referential style of a professor to whom students are required to listen. Clubby asides about professors Mr. Ellis has known seem of doubtful interest to any reader. Footnotes at the bottom of the page add tedious details, such as a rumination on the label “Treaty of Paris” versus “Peace of Paris” and the least interesting tidbit I have ever read about the usually fascinating Marquis de Lafayette.

The book reads as though it had been written for someone who hasn’t picked up a book or newspaper since 1976. One footnote picks a bone with Marxist scholarship in a long-dead historiographic battle. The cultural references tend toward Dr. Spock and World War II air raids. If Mr. Ellis had published “The Cause” in 1976, it might have been correct that American readers were “perhaps for the first time” equipped to empathize with Britain’s 18th-century plight as a “newly arrived world power moving onto the global stage with overwhelming confidence, brimming over with a bottomless sense of its omniscience and invincibility, stepping into a military quagmire.” But nearly half a century after the fall of Saigon, readers in 2021 won’t find the idea of a military quagmire and a lost sense of invincibility anything new.

Of course history books don’t have to tell us anything new. An engagingly written work of history can cover old ground and still be enjoyable, like reading a beloved classic. Yet “The Cause” combines the worst quality of popular history (not saying anything original) with the worst qualities of academic writing (it is dully written). Reading the book means slogging through cluttered and repetitive sentences. Read this one: “While The Cause provided at least a measure of verbal focus before ‘War for American Independence’ or ‘American Revolution’ became viable labels, the fundamental ambiguity of The Cause is symptomatic of the inherently elusive character of American resistance to British rule in 1775-76, which simultaneously embraced the sword and the olive branch.” This states an important point: American rebels weren’t ready to call their protests a revolution or independence movement before the Declaration of Independence. But the observation is neither original nor well-put.

The table of contents for “The Cause” promises some new characters beyond those Mr. Ellis has written about before, including George Washington’s enslaved valet, William Lee, and Catharine Littlefield Greene, the wife of Gen. Nathanael Greene. Yet these sections of the book turn out to be thin two-page profiles with little connection to the book’s main text. Mr. Ellis shoehorns Mohawk war leader Joseph Brant into being “the George Washington of the vaunted Iroquois Confederacy.” Yet writing about Brant doesn’t make Mr. Ellis rethink the bromide that he delivers in the main text—that, because of viruses, “the Native population collapsed upon contact with the front edge of white settlements.” Never mind that Mohawks had traded, lived with, and intermarried with the Dutch, French and English (and their germs) for nearly two centuries by the time of the Revolution.

In another brief profile, Mr. Ellis writes (twice) that Mercy Otis Warren was the “best friend” of Abigail Adams but omits her stinging published condemnation of the Constitution. In her pamphlet “Observations on the New Constitution,” Otis Warren accused the drafters of the Constitution of a “deep-laid plot” against “a people who have made the most costly sacrifices in the cause of liberty—who have braved the power of Britain, weathered the convulsions of war, and waded thro’ the blood of friends and foes to establish their independence.” In a work about different goals subsumed under “The Cause,” surely her charge that the Constitution would betray that cause deserves further exploration.

Since 1976, historians have been moving away from this kind of sidebar treatment of everyone but the Founding Fathers. Thus, we have such books as Serena Zabin’s “The Boston Massacre: A Family History” (2020) which by integrating the stories of British and American soldiers and their wives demonstrates how intimate a breakup the Revolution was. Colin G. Calloway’s “The Indian World of George Washington” (2018) traces Native American influence on Washington’s life, from his childhood, through his military career, to the Native diplomacy and warfare that commanded his attention during his presidency. Annette Gordon-Reed’s “The Hemingses of Monticello” (2008) reveals the deep intertwining of the white and black relations of Thomas Jefferson and his wife, Martha Wayles Jefferson.

By not using the lives of Joseph Brant, Mercy Otis Warren or William Lee to deepen the story of the American Revolution, Mr. Ellis is left presenting the shallow interpretation that the Revolution merely deferred including women and nonwhite men in political equality. It’s true that many of the Founding Fathers lamented slavery and the slave trade and hoped that they would end eventually, but they rarely imagined extending full citizenship rights to black men. Because women were considered dependents, they were by definition incapable of exercising the independence required of citizens in a republic. Abigail Adams urged her husband to “remember the ladies” in making laws that affected them, but her husband decidedly opposed expanding the franchise to anyone whose wealth, position and gender didn’t allow them to be independent. The common law of coverture, which made married women legal dependents of their husbands, survived the Revolution without even much being mentioned. After Thomas Jefferson won the presidency in 1800, his supporters in the Maryland state legislature changed the state’s rules to take the vote away from “free negroes and mulattoes” who had voted in previous elections. In 1807, New Jersey added the words “male” and “white” to its state constitution. Political equality for women and nonwhite men wasn’t deferred after the revolution; it moved further away.

In my decades as a historian, I have never seen early American history as urgently consumed and debated as it is now, from all parts of the political spectrum. Who is an American? What makes a good and lasting republic? Should legislators be responsible to the people or govern from their own sense of right and wrong? How do we build and maintain lasting representative institutions? What should happen when a candidate loses an election but thinks the election was run unfairly? How does a minority change the majority’s mind? These are all questions that Americans struggled with 250 years ago. The founding of our country began to answer some of them in revolutionary ways, but they are certainly not settled today.

There are good general histories of the American Revolution to read as the semiquincentennial approaches. Alan Taylor’s “American Revolutions” (2016) is a gripping and original synthesis. Classics such as Robert Middlekauff’s “The Glorious Cause” (1982, revised 2005) and Edward Countryman’s “The American Revolution” (1985, revised 2003) may already be on your shelf and ripe for a reread. Grab one of those, and get those Betsy Ross flags ready.

—Ms. DuVal, a professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, is the author of “Independence Lost: Lives on the Edge of the American Revolution.”

That was one tough review. (It sounds like a boring text book.)

The book is:

The Cause: The American Revolution and Its Discontents, 1773-1783

By Joseph J. Ellis

Liveright

400 pages

Sounds lazy if he didn't go all the way to 1789.

The Revolution wasn't over until the Constitution was ratified in 1789.

Then the Amendments started and one could argue that we aren't done yet, with either the Revolution or the Constitution.

(or the British)

I hear ya.

The criminals who looted and sacked the US Capital January 6th for Donald Trump were not righteous patriots fighting for liberty and freedom. They were violent insurrectionists bent upon overthrowing our 2020 Presidential election. They deserve no respect.

That's strange. He doesn't claim the colonies revolted to protect their right to own slaves.

He hasn't gotten the word yet.

Slavery was legal under British law until 1833.

It just wasn't an issue with the British, but it was much more important to the Southern colonies than the Northern ones.

Several of the Northern colonies outlawed slavery before ratifying the Articles of Confederation.

Others established timetables to phase it out.

The British, by 1775, were singing a different tune altogether. They began promising freedom to slaves that would support the British

as laborers or camp followers.

T Jefferson estimated as many as 30,000 had been confiscated or ran away to join the Brits.

Ironically, the Brits kept their word, sort of, eventually transporting a few thousand to England or the Caribbean and as many as 20,00 to Nova Scotia.

By 1777 Congress stopped blocking black enlistment over fears of future uprisings and started recruiting them.

Every northern colony and MD recruited blacks into integrated units.

NE blacks received the same pay as everyone else but never achieved higher rank than Corporal.

Southern states even refused a $1,000 bounty to supply slaves to Washington's army as free soldiers or laborers.

That racism ran deep in some people.

Exactly. Which is why it's preposterous to claim a principal motive of the revolution was to protect the right to own slaves.

They began promising freedom to slaves that would support the British

No, they confiscated slaves and promised freedom only to those slaves owned by rebels. Slaves owned by loyalists were returned to their owner. The motive wasn't to free slaves, or take them from loyal British subjects, but to punish rebels.

Said who, where ? It was a factor, it was a PITA as far as getting the drunks of Congress to agree on many things

but I have never claimed it was a "principle motive".

True in principal, but only 6,000 slaves were returned to their owners before they moved to Florida, maybe 2,000 that

went to Canada, lots of blacks just walked away. Freed blacks went to Canada and after a few years back to Africa to establish Sierra Leone.

I guess the joke was on the people who moved to Florida to deal with the Seminoles and the Spanish, the blacks walked away and joined the Seminoles to the point of starting the first Seminole war.

Upwards of 60,000 english speaking loyalists moved to Ontario & New Brunswick with the

promises of free land in British NA and a 1790 Royal assurance that slavery would never end in the British Empire.

Another joke on the loyalists.

I didn't say you did. Perhaps you forgot about the rather famous racialist propaganda project that teaches our kids that fake narrative.

Virtually all Americans from the colonial era believed blacks (the Africans) were inferior. That is the starting point for any discussion about the "founding' and slavery or racism.

In the north there werent as many large fields to work, nor the proper crops demanding backbreaking labor. I think the northern colonists were also more willing to do the work themselves. In the south there were a lot of lazy ass patrician types who wanted to be supervisors not workers, hence slavery in the US began in Virginia not Boston.

It was all about the money and the circumstances. In the beginning English indentured servants were used but in time the supply of them diminished and they became more expensive. The price of Negro slaves came down for various reasons, and the Africans became the slave population.

AT BEST, the behavior and views of the founding fathers was inadequate and embarrasing as regards slavery. Thats just the facts.

So you just needed to deflect to something we were not discussing.

Got it.

That’s 1619 project material.

Jbb They are domestic terrorists traitorous scum

The BLM and Antifa looters and rioters were and are exactly that.

A/noon.

And don't forget another one of the reasons was Britain using America as a dumping ground for its convicts. Approximately 52,000 convicts were sent over and that caused a lot of resentment. In some of the States they tried to get the practice banned but it was over ruled by the King. So it wasn't just about black slaves but white convicts...

So you mob were the original convict dumping ground, until the War of Independence...