‘Those kids never got to go home’

http://www.philly.com/philly/news/Those_kids_never_got_to_go_home.html

CARLISLE, Pa. — They want the bones of their children back.

They want the remains of the boys and girls who were taken from their American Indian families in the West, spirited a thousand miles to the East, and, when they died not long after arrival, were buried here in the fertile Pennsylvania soil.

The brevity of those lives, and the effort of a South Dakota tribe to reclaim them now, spring from a turn-of-the-century episode of forced assimilation and cultural destruction — one that continues to haunt and torment the Rosebud Sioux.

Rosebud Sioux.

Today, many people know this small borough as a stop on the turnpike or as the site of Dickinson College.

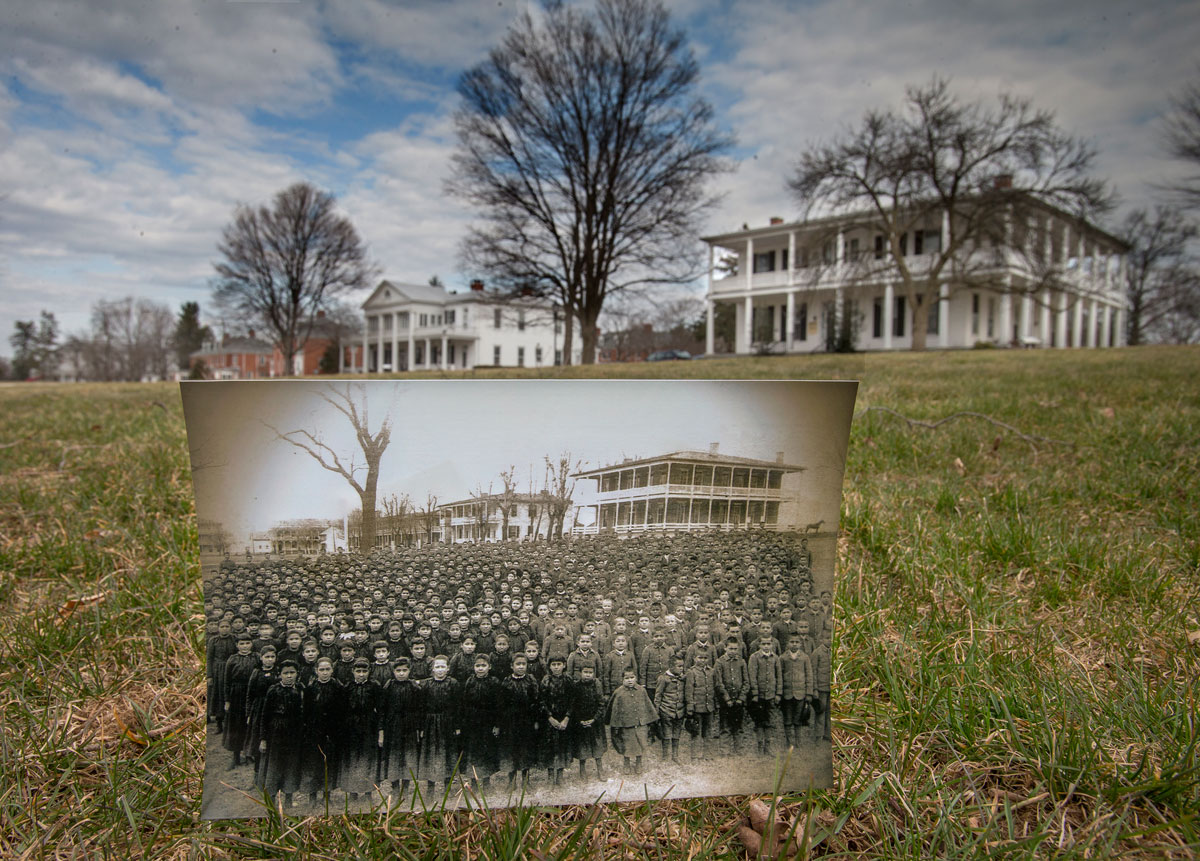

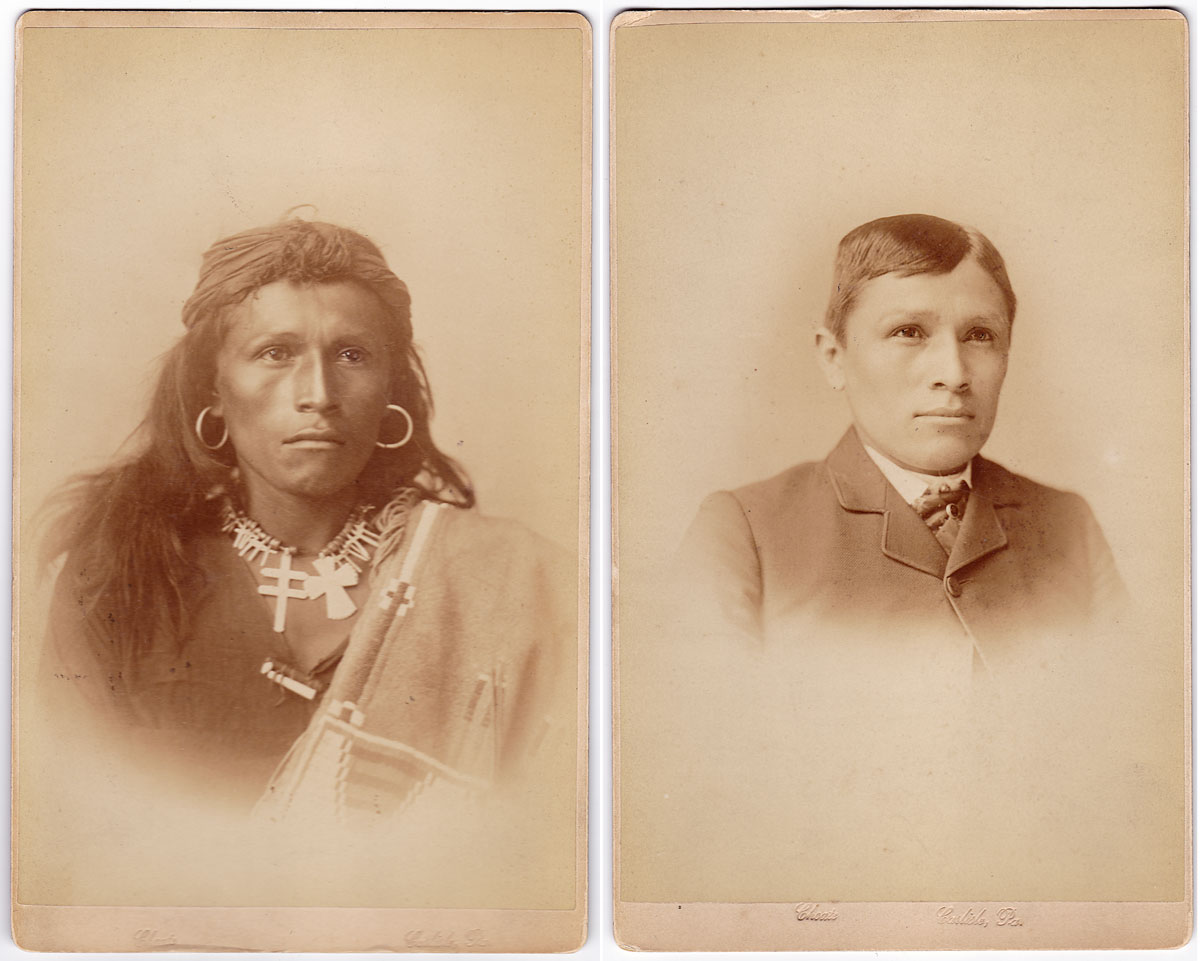

But from 1879 to 1918, the town was home to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, the flagship of a fleet of federally funded, off-reservation boarding schools. It immersed native children in the dominant white culture, seeking to cleanse their "savage nature" by erasing their names, language, dress, customs, religions, and family ties.

The Carlisle goal: "Kill the Indian, save the man."

Sometimes, both perished. Nearly 200 children are buried here in the Indian cemetery.

Now the Rosebud Sioux seek to have at least 10 tribe members brought back to the reservation, where they can be reburied after appropriate native prayers and services.

"We talk about historical trauma," said Russell Eagle Bear, the tribe's historic-preservation officer. "A hundred and thirty years later, this still has an impact on our youth. We're trying to make peace with those spirits and bring them home."

It's no simple act of graves repatriation. The cemetery lies within the perimeter of the Carlisle Barracks, an Army installation that once was the grounds of the Indian school. The tribe asked the Army in January to return its children's remains and the Army said no.

That's OK, Eagle Bear said. Senators and congresspeople are getting involved — and other Indian nations too. The tribe is planning a pilgrimage from South Dakota to Carlisle this summer.

This modern battle over the past, he said, is just beginning.

In a way, the Sioux recovery effort began at the White House.

Two dozen Rosebud teenagers traveled to Washington last summer for the Obama administration's first Tribal Youth Gathering, held in collaboration with UNITY, the United National Indian Tribal Youth.

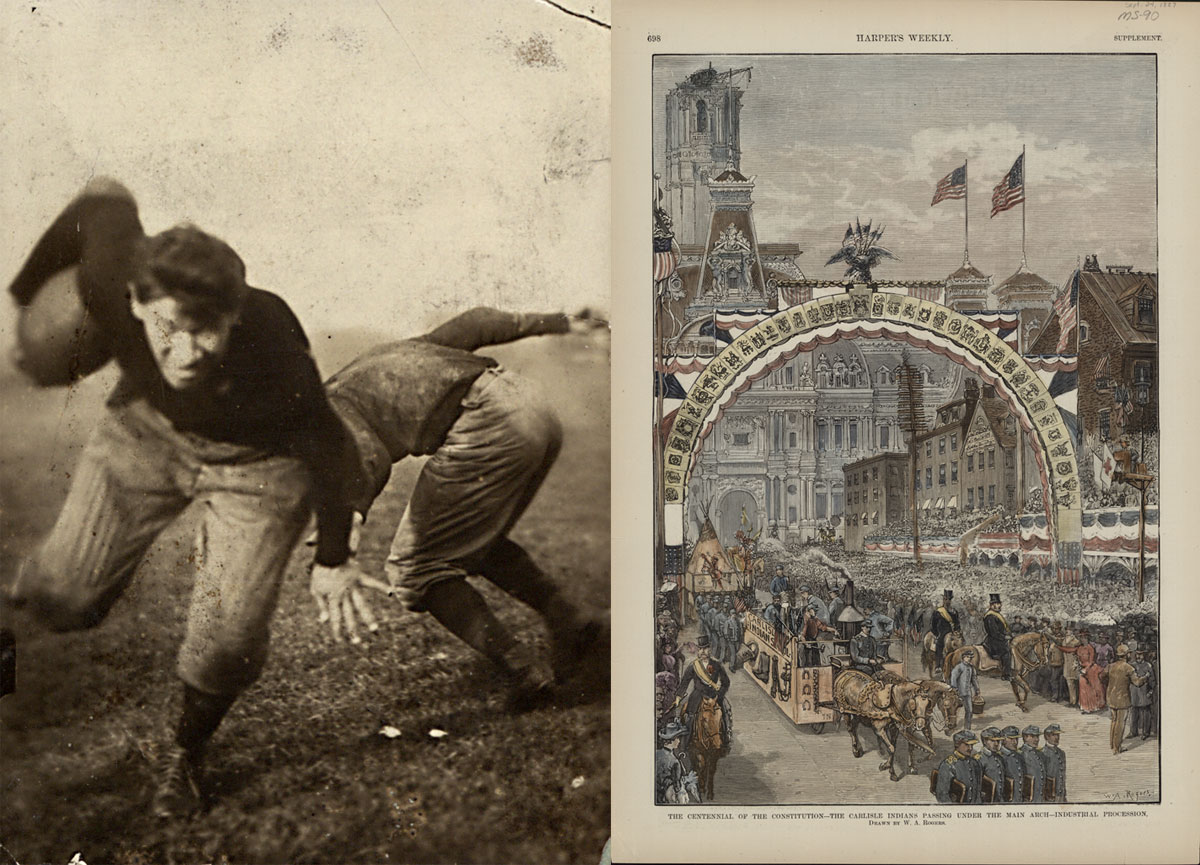

Afterward, the group drove north to see the site of the Indian school, widely known for its association with sports legend Jim Thorpe, and to visit the cemetery.

Sydney Horse Looking, 17, became upset upon being stopped at the Army barracks gate for a mandatory security check — "I have to prove my identity to visit my ancestors?" — and even more emotional when she reached the graveyard.

"Those kids never got to go home," she said in an interview. "I would wonder why no one came and got me: 'Why am I still here?'"

The Rosebud youths placed candy on the graves. They sang prayer songs and called out the names of the children.

As the group prepared to leave, the cemetery filled with swarms of flashing fireflies.

"It was like their spirits let us know they heard those prayers," said Micah Lunderman, a Rosebud youth counselor who helped lead the trip. "We know they heard us."

Back home in Rosebud, the youths asked the Tribal Council: "Why aren't we doing something to bring them home?"

No one knew the answer.

In January the Rosebud Tribal Council passed a formal resolution to seek the return of the remains and wrote to President Obama and other federal authorities.

"It's pretty unusual," said David Beck, a Native American studies professor at the University of Montana. "If the Rosebud Sioux are successful, other tribes will quickly take notice."

The cemetery isn't half the size of a football field, 186 graves in a rectangular lawn, surrounded by a chest-high iron fence.

On the ground by the bleached white markers, visitors have left children's toys, gifts of cloth horses, dolls, and tiny plastic dinosaurs.

The most noticeable grave — first row, first stone — belongs to Lucy Pretty Eagle, one of at least 10 Rosebud children to die at the school.

Two others, Maud, the daughter of Chief Swift Bear, and Ernest, son of Chief White Thunder, arrived together the day the school opened on Oct. 6, 1879 — and died on the same day 14 months later.

One marker is inscribed "Friend HH Bear," a shortening of Friend Hollow Horn Bear, who died in 1886.

That child, said Duane Hollow Horn Bear, was his grandfather's older sister. Her faraway death and burial still tears at his family.

"I feel pain," Hollow Horn Bear said by phone from South Dakota. "Bring our people home."

He teaches Lakota studies at Sinte Gleska University on the reservation. But no one needs textbooks to know what happened at Carlisle, he said. Just look at the photos.

"None of the kids are smiling," Hollow Horn Bear said. "They had nothing to smile about."

The boys, some as young as 4, wore Army-style uniforms, the girls long dresses. Children who spoke their native language could be beaten.

Many were kept from their families even in summer, sent to local households to provide ongoing immersion and, for the white hosts, cheap labor.

"Discipline was constant," Norman Matteoni wrote in Prairie Man , his study of Sitting Bull. "Punishment, abuse, and illness were frequent."

So was death. In the cemetery lie children from more than three dozen Indian nations, their lives documented by Cumberland County historian Barbara Landis and Australian anthropologist Genevieve Bell, experts on the school.

The headstones show no birth dates or ages. Some misspell names. Thirteen are marked "Unknown."

The children died from tuberculosis, pneumonia, flu. Some could not survive the pain of separation from their families, their health impaired by the school's strict military routine.

In the first decade, 96 children died, according to Jacqueline Fear-Segal, an authority on American history. Preston McBride, an Indian studies scholar, estimates that more than 500 students died at Carlisle or soon after they left, sent home by the school when it became clear they were too ill to survive.

Overcrowding, labor, physical abuse, and malnourishment weakened students' immune systems and left them prey to epidemics that swept the school, McBride found.

The dead were buried near the athletic fields, that cemetery moved in 1927 to an isolated patch by the rear gate. After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, security changes turned the back gate into the main entrance, giving the graves prominence.

"For me, going through [the cemetery] is extremely draining," Landis said. "Because I have children and I have grandchildren. My children never went to a school where there's a cemetery."

In his grave at Arlington National Cemetery, Richard Henry Pratt surely must be spinning. He always knew what was best for Indians.

A self-righteous former 10th Cavalry commander and frontier Indian fighter, he had the idea to solve "the Indian problem" by forcing natives to acculturate.

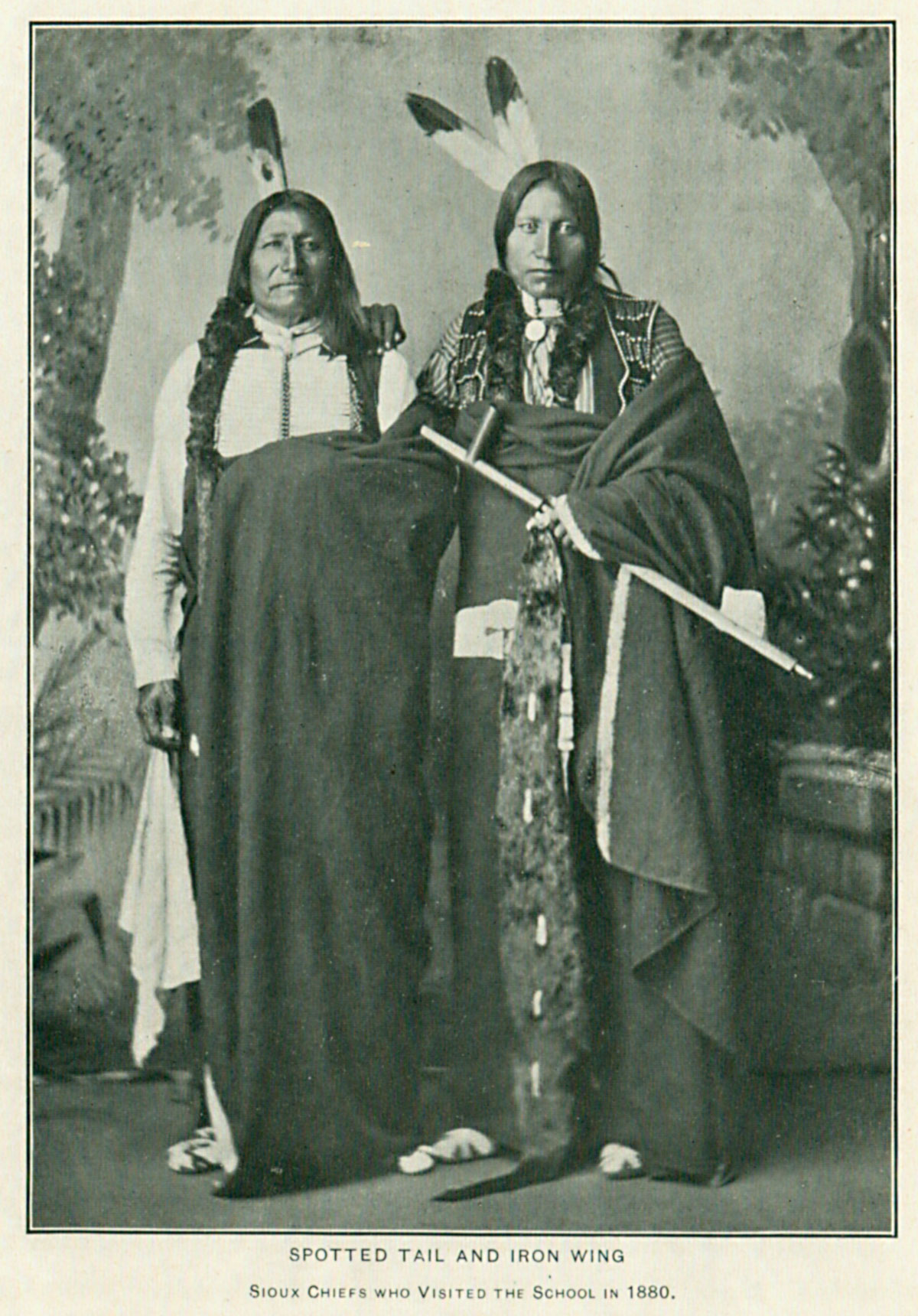

He won approval to use the old barracks as a campus, then traveled to Dakota Territory, first to Rosebud, where he persuaded Chief Spotted Tail to send several dozen children, and on to Pine Ridge.

Pratt argued to tribal leaders that if Indians had been better able to speak and read English, they would not have been so abused in treaty negotiations. At a time when Indians were being forced onto reservations, he promised the children would be safe, fed, and taught to make their way in the white man's world.

The two tribes sent 82 children, who embarked on a long and often alarming journey by horse, steamboat, and train. At stations along the way, white people gathered to gape at the youths. The locomotive stopped in Sioux City, Iowa, moved east to Chicago, eventually reached Harrisburg, then turned southwest to Carlisle, a town of about 7,000.

Many were relatives of chiefs or powerful leaders. Coming only three years after Custer’s troops were wiped out at the Little Big Horn, it placed chiefs' children securely in white hands.

"They were hostages," Eagle Bear said.

But the school wasn't created to commit evil. Pratt and his Quaker and Christian-missionary allies thought they were doing a good thing, a noble thing, helping to save a vanishing race.

"We invite the Germans to come into our country and communities and share our customs, our civilization," Pratt lectured in 1892. "Why not try it on the Indians?"

Some Indians agreed with him. The world was changing fast, and Indian leaders saw that white men, once rare, now covered the land like ants.

Carlisle's enrollment grew to 1,000 a year. The band performed at presidential inaugurations, and in the early 1900s the football team became a national powerhouse, led by Thorpe and coached by Pop Warner.

Today Carlisle's legacy, scholars say, is at best conflicted, creating opportunities for some students, but causing confusion and even deaths among others, its role as a prototype helping to spread misery.

Indian children often were seized from their families. Some reservation parents were told to give up their young ones — or their food rations.

What some researchers now call "boarding school survivors" shared harrowing tales of brutality and sexual abuse.

Carlisle Indian

Industrial School

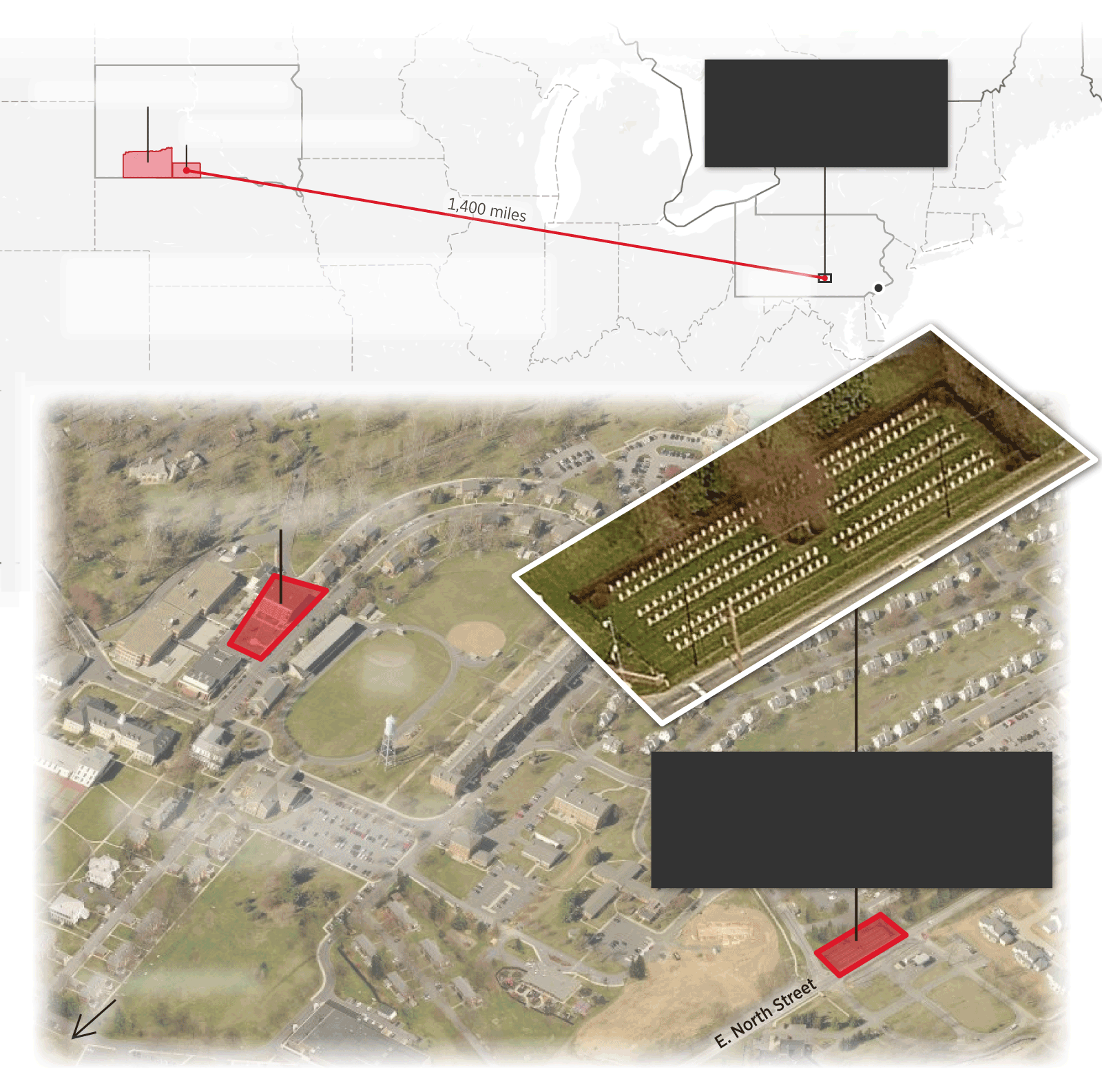

Pine Ridge Reservation

S.D.

Rosebud Reservation

Carlisle, Pa.

Neb.

Pa.

In 1879, the journey from the Rosebud Reservation to

the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania

took four days by train. Today it is a 21-hour drive.

Area of

detail

Ohio

Philadelphia

Site of original cemetery

Indian

Field

Indian School Cemetery

The cemetery was moved to an isolated

patch by the rear gate in 1927, which

later became the front gate.

Carlisle Indian Industrial School

(now Carlisle Barracks)

Downtown Carlisle

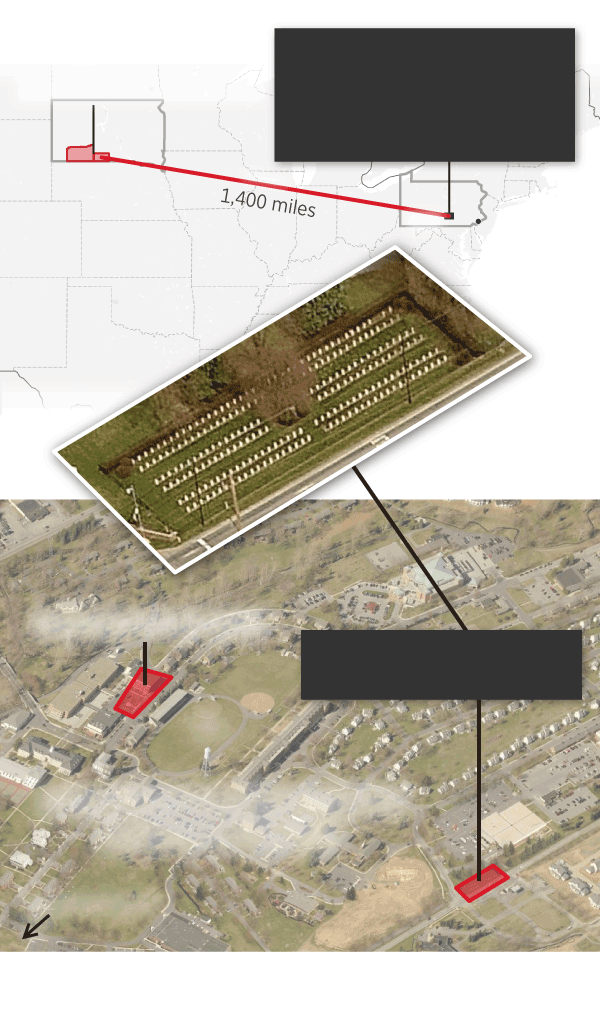

Carlisle Indian

Industrial School

Pine Ridge and

Rosebud Reservations

Carlisle, Pa.

S.D.

Mont.

Pa.

Philadelphia

Site of original cemetery

Indian School Cemetery

Indian

Field

Carlisle Indian Industrial School

(now Carlisle Barracks)

Downtown Carlisle

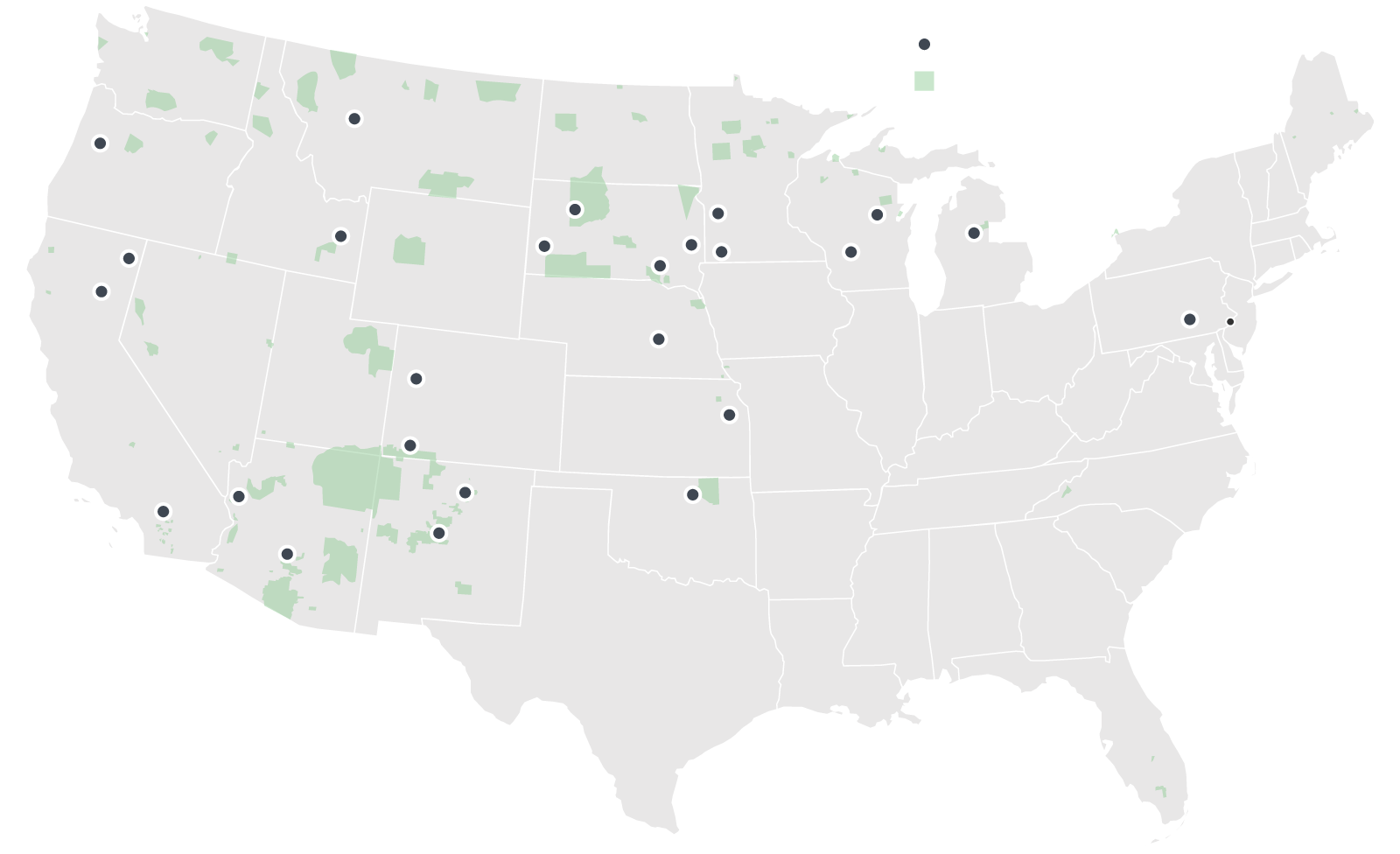

That suffering contributes to social ills that now plague Indian communities, said Denise Lajimodiere, a board member of the Colorado-based National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, which seeks redress.

"It was an attempt at genocide," said Lajimodiere, an assistant education professor at North Dakota State University in Fargo. "I want the whole United States to know what happened to us. I want the whole world to know what happened to us."

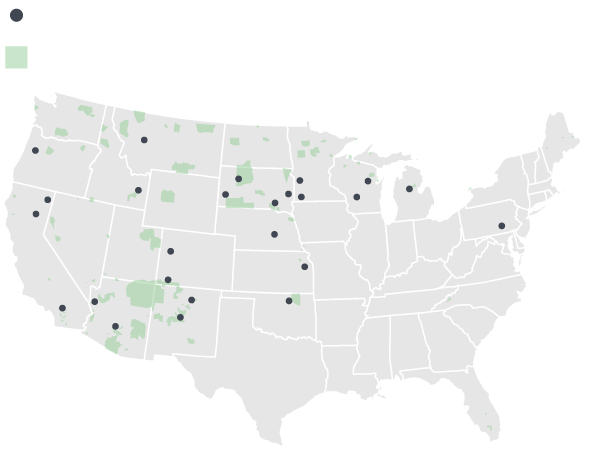

Indian Boarding School

American Indian Reservations

Fort Shaw

Mont.

Chemawa

Salem

Minn.

Cheyenne River

Wittenberg

Ore.

Fort Hall

Morris

Idaho Falls

Idaho

Flandreau

Wis.

Mount Pleasant

Rapid City

S.D.

Tomah

Pipestone

Fort Bidwell

Mich.

Chamberlain

Greenville

Carlisle

Pa.

Neb.

Philadelphia

Genoa

Grand Junction

Calif.

Colo.

Haskell

Kan.

Lawrence

Fort Lewis

Fort Mojave

Durango

Bullhead City

Santa Fe

Chilocco

Sherman High

Ponca City

Okla.

Ariz.

Riverside

Albuquerque

Phoenix

N.M.

Indian Boarding School

American Indian Reservations

Fort Shaw

Chemawa

Carlisle

Greenville

Haskell

Albuquerque

The push for repatriation is gaining strength.

The Northern Arapaho, a Wyoming tribe, want the remains of three children returned from Carlisle. The Great Plains Tribal Chairman's Association went further, calling for remains at all boarding school sites to be returned upon request.

igns emerged this month that the Army's position might shift.

"Our desire is to work with the Rosebud Sioux, Northern Arapaho, and any other interested tribes to bring this issue to resolution," Army spokesperson Dave Foster said.

The Army wants to meet with the two tribes in government-to-government consultation, to address the legal requirements involved in disinterment, he said.

Some in Rosebud are optimistic.

"We have a lot of momentum," said Lunderman, the youth counselor. "We believe there's going to be a good outcome. ... It's really going to bring a lot of closure to our families."

jgammage@phillynews.com 215-854-4906 @JeffGammage

I apologize about the formatting - so many pictures - and the length of the thread.

BUT - this is a story and history that EVERYONE should be aware of. Click the link above and read the complete article and view the pictures - it'll break your heart.

Yeah - Kill the Indian - Save the Man.

Thanks Pratt.

Perhaps because of where I am or my internet service I cannot see any of the photos. However, I am sad to say that the story is no surprise to me, because Indian children were not treated better in Canada.

I'm sorry so many here prefer political crap on the front, but I, and many others, believe this information needs to be brought out.

There is no shortage of Indian related articles on this site.

Give your complaining a rest.

John - go have a beer - get some sleep - try again tomorrow.

You would prefer Terump - Billary - Sandels - Crush - Rubbit?????

John, you are not the arbiter of what gets published on this site-- none of us are. Give YOUR complaining a rest!

One of the saddest chapters in history for American Indians. The aftermath is still felt today. The last of these schools did not close until the 1980's. In addition to the off rez boarding schools, there were a number of on rez schools, that were no better than the off rez boarding schools.

As for Carlisle, out of the total number of students that were sent there, only 150 ever graduated. These were not schools but work camps, that is the kindest word I have for them.

There is at least one off Rez Boarding schools not shown on the map. Wahpeton Indian Boarding Schools in Wahpeton ND. Right on the Red River the border with Minnesota. Floyd Red Crow Westerman, Dennis Banks, Russell Means were ''students'' there.

These children need to be returned to their tribes, PERIOD..

What is needed in the U.S. is a commission to investigate the Indian Boarding Schools, similar to the one that Canada had.

I doubt that will ever happen here.

You have to ask yourself, why?

What so many of us would like to see is a commission - a true commission with power to enforce their recommendations - to review the treatment of Native Americans - period.

110% agreement on that, 1st.

This is something that would haunt a community for its lifetime... Their children-- their hope and purpose-- taken from them, shipped out and killed. Let their poor little bodies be reclaimed, but I believe the markers should remain, as a reminder, of the sweet little souls who never got to go home.

The sadness is overwhelming.