What the Pandemic Has Taught Us About Science

The Covid-19 pandemic has stretched the bond between the public and the scientific profession as never before. Scientists have been revealed to be neither omniscient demigods whose opinions automatically outweigh all political disagreement, nor unscrupulous fraudsters pursuing a political agenda under a cloak of impartiality. Somewhere between the two lies the truth: Science is a flawed and all too human affair, but it can generate timeless truths, and reliable practical guidance, in a way that other approaches cannot.

In a lecture at Cornell University in 1964, the physicist Richard Feynman defined the scientific method. First, you guess, he said, to a ripple of laughter. Then you compute the consequences of your guess. Then you compare those consequences with the evidence from observations or experiments. “If [your guess] disagrees with experiment, it’s wrong. In that simple statement is the key to science. It does not make a difference how beautiful the guess is, how smart you are, who made the guess or what his name is…it’s wrong.”

So when people started falling ill last winter with a respiratory illness, some scientists guessed that a novel coronavirus was responsible. The evidence proved them right. Some guessed it had come from an animal sold in the Wuhan wildlife market. The evidence proved them wrong. Some guessed vaccines could be developed that would prevent infection. The jury is still out.

Seeing science as a game of guess-and-test clarifies what has been happening these past months. Science is not about pronouncing with certainty on the known facts of the world; it is about exploring the unknown by testing guesses, some of which prove wrong.

Bad practice can corrupt all stages of the process. Some scientists fall so in love with their guesses that they fail to test them against evidence. They just compute the consequences and stop there. Mathematical models are elaborate, formal guesses, and there has been a disturbing tendency in recent years to describe their output with words like data, result or outcome. They are nothing of the sort.

An epidemiological model developed last March at Imperial College London was treated by politicians as hard evidence that without lockdowns, the pandemic could kill 2.2 million Americans, 510,000 Britons and 96,000 Swedes. The Swedes tested the model against the real world and found it wanting: They decided to forgo a lockdown, and fewer than 6,000 have died there.

In general, science is much better at telling you about the past and the present than the future. As Philip Tetlock of the University of Pennsylvania and others have shown, forecasting economic, meteorological or epidemiological events more than a short time ahead continues to prove frustratingly hard, and experts are sometimes worse at it than amateurs, because they overemphasize their pet causal theories.

A second mistake is to gather flawed data. On May 22, the respected medical journals the Lancet and the New England Journal of Medicine published a study based on the medical records of 96,000 patients from 671 hospitals around the world that appeared to disprove the guess that the drug hydroxychloroquine could cure Covid-19. The study caused the World Health Organization to halt trials of the drug.

It then emerged, however, that the database came from Surgisphere, a small company with little track record, few employees and no independent scientific board. When challenged, Surgisphere failed to produce the raw data. The papers were retracted with abject apologies from the journals. Nor has hydroxychloroquine since been proven to work. Uncertainty about it persists.

A third problem is that data can be trustworthy but inadequate. Evidence-based medicine teaches doctors to fully trust only science based on the gold standard of randomized controlled trials. But there have been no randomized controlled trials on the wearing of masks to prevent the spread of respiratory diseases (though one is now under way in Denmark). In the West, unlike in Asia, there were months of disagreement this year about the value of masks, culminating in the somewhat desperate argument of mask foes that people might behave too complacently when wearing them. The scientific consensus is that the evidence is good enough and the inconvenience small enough that we need not wait for absolute certainty before advising people to wear masks.

This is an inverted form of the so-called precautionary principle, which holds that uncertainty about possible hazards is a strong reason to limit or ban new technologies. But the principle cuts both ways. If a course of action is known to be safe and cheap and might help to prevent or cure diseases—like wearing a face mask or taking vitamin D supplements, in the case of Covid-19—then uncertainty is no excuse for not trying it.

Passengers wear face masks aboard a New York City subway traveling through Brooklyn in August.

PHOTO: ROBERT NICKELSBERG/GETTY IMAGES

A fourth mistake is to gather data that are compatible with your guess but to ignore data that contest it. This is known as confirmation bias. You should test the proposition that all swans are white by looking for black ones, not by finding more white ones. Yet scientists “believe” in their guesses, so they often accumulate evidence compatible with them but discount as aberrations evidence that would falsify them—saying, for example, that black swans in Australia don’t count.

Advocates of competing theories are apt to see the same data in different ways. Last January, Chinese scientists published a genome sequence known as RaTG13 from the virus most closely related to the one that causes Covid-19, isolated from a horseshoe bat in 2013. But there are questions surrounding the data. When the sequence was published, the researchers made no reference to the previous name given to the sample or to the outbreak of illness in 2012 that led to the investigation of the mine where the bat lived. It emerged only in July that the sample had been sequenced in 2017-2018 instead of post-Covid, as originally claimed.

These anomalies have led some scientists, including Dr. Li-Meng Yan, who recently left the University of Hong Kong School of Public Health and is a strong critic of the Chinese government, to claim that the bat virus genome sequence was fabricated to distract attention from the truth that the SARS-CoV-2 virus was actually manufactured from other viruses in a laboratory. These scientists continue to seek evidence, such as a lack of expected bacterial DNA in the supposedly fecal sample, that casts doubt on the official story.

By contrast, Dr. Kristian Andersen of Scripps Research in California has looked at the same confused announcements and stated that he does not “believe that any type of laboratory-based scenario is plausible.” Having checked the raw data, he has “no concerns about the overall quality of [the genome of] RaTG13.”

Given that Dr. Andersen’s standing in the scientific world is higher than Dr. Yan’s, much of the media treats Dr. Yan as a crank or conspiracy theorist. Even many of those who think a laboratory leak of the virus causing Covid-19 is possible or likely do not go so far as to claim that a bat virus sequence was fabricated as a distraction. But it is likely that all sides in this debate are succumbing to confirmation bias to some extent, seeking evidence that is compatible with their preferred theory and discounting contradictory evidence.

Dr. Andersen, for instance, has argued that although the virus causing Covid-19 has a “high affinity” for human cell receptors, “computational analyses predict that the interaction is not ideal” and is different from that of SARS, which is “strong evidence that SARS-CoV-2 is not the product of purposeful manipulation.” Yet, even if he is right, many of those who agree the virus is natural would not see this evidence as a slam dunk.

As this example illustrates, one of the hardest questions a science commentator faces is when to take a heretic seriously. It’s tempting for established scientists to use arguments from authority to dismiss reasonable challenges, but not every maverick is a new Galileo. As the astronomer Carl Sagan once put it, “Too much openness and you accept every notion, idea and hypothesis—which is tantamount to knowing nothing. Too much skepticism—especially rejection of new ideas before they are adequately tested—and you’re not only unpleasantly grumpy, but also closed to the advance of science.” In other words, as some wit once put it, don’t be so open-minded that your brains fall out.

Peer review is supposed to be the device that guides us away from unreliable heretics. A scientific result is only reliable when reputable scholars have given it their approval. Dr. Yan’s report has not been peer reviewed. But in recent years, peer review’s reputation has been tarnished by a series of scandals. The Surgisphere study was peer reviewed, as was the study by Dr. Andrew Wakefield, hero of the anti-vaccine movement, claiming that the MMR vaccine (for measles, mumps and rubella) caused autism. Investigations show that peer review is often perfunctory rather than thorough; often exploited by chums to help each other; and frequently used by gatekeepers to exclude and extinguish legitimate minority scientific opinions in a field.

Herbert Ayres, an expert in operations research, summarized the problem well several decades ago: “As a referee of a paper that threatens to disrupt his life, [a professor] is in a conflict-of-interest position, pure and simple. Unless we’re convinced that he, we, and all our friends who referee have integrity in the upper fifth percentile of those who have so far qualified for sainthood, it is beyond naive to believe that censorship does not occur.” Rosalyn Yalow, winner of the Nobel Prize in medicine, was fond of displaying the letter she received in 1955 from the Journal of Clinical Investigation noting that the reviewers were “particularly emphatic in rejecting” her paper.

The health of science depends on tolerating, even encouraging, at least some disagreement. In practice, science is prevented from turning into religion not by asking scientists to challenge their own theories but by getting them to challenge each other, sometimes with gusto. Where science becomes political, as in climate change and Covid-19, this diversity of opinion is sometimes extinguished in the pursuit of a consensus to present to a politician or a press conference, and to deny the oxygen of publicity to cranks. This year has driven home as never before the message that there is no such thing as “the science”; there are different scientific views on how to suppress the virus.

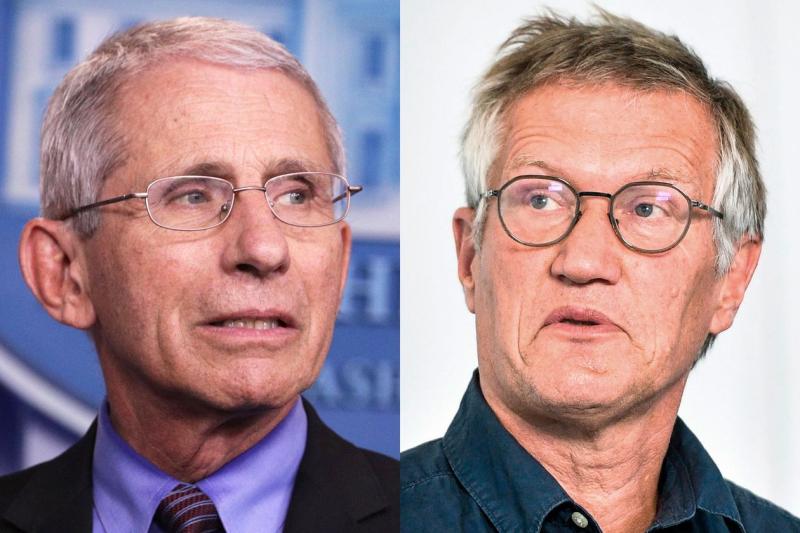

Anthony Fauci, the chief scientific adviser in the U.S., was adamant in the spring that a lockdown was necessary and continues to defend the policy. His equivalent in Sweden, Anders Tegnell, by contrast, had insisted that his country would not impose a formal lockdown and would keep borders, schools, restaurants and fitness centers open while encouraging voluntary social distancing. At first, Dr. Tegnell’s experiment looked foolish as Sweden’s case load increased. Now, with cases low and the Swedish economy in much better health than other countries, he looks wise. Both are good scientists looking at similar evidence, but they came to different conclusions.

Having proved a guess right, scientists must then repeat the experiment. Here too there are problems. A replication crisis has shocked psychology and medicine in recent years, with many scientific conclusions proving impossible to replicate because they were rushed into print with “publication bias” in favor of marginally and accidentally significant results. As the psychologist Stuart Ritchie of Kings College London argues in his new book, “Science Fictions: Exposing Fraud, Bias, Negligence and Hype in Science,” unreliable and even fraudulent papers are now known to lie behind some influential theories.

For example, “priming”—the phenomenon by which people can be induced to behave differently by suggestive words or stimuli—was until recently thought to be a firmly established fact, but studies consistently fail to replicate it. In the famous 1971 Stanford prison experiment, taught to generations of psychology students, role-playing volunteers supposedly chose to behave sadistically toward “prisoners.” Tapes have revealed that the “guards” were actually instructed to behave that way. A widely believed study, subject of a hugely popular TED talk, showing that “power posing” gives you a hormonal boost, cannot be replicated. And a much-publicized discovery that ocean acidification alters fish behavior turned out to be bunk.

Prof. Ritchie argues that the way scientists are funded, published and promoted is corrupting: “Peer review is far from the guarantee of reliability it is cracked up to be, while the system of publication that’s supposed to be a crucial strength of science has become its Achilles heel.” He says that we have “ended up with a scientific system that doesn’t just overlook our human foibles but amplifies them.”

At times, people with great expertise have been humiliated during this pandemic by the way the virus has defied their predictions. Feynman also said: “Science is the belief in the ignorance of experts.” But a theoretical physicist can afford such a view; it is not much comfort to an ordinary person trying to stay safe during the pandemic or a politician looking for advice on how to prevent the spread of the virus. Organized science is indeed able to distill sufficient expertise out of debate in such a way as to solve practical problems. It does so imperfectly, and with wrong turns, but it still does so.

Mr. Ridley is a member of the House of Lords and the author, most recently, of “How Innovation Works: And Why It Flourishes in Freedom.”

Article is LOCKED by author/seeder

Article is LOCKED by author/seeder

Sad to say science like so many other things has been politicized. It seems to me that many scientists have morphed into becoming spokesmen for their own causes and on rare occasion it has been about self promotion.

The article has already been removed from the link.

I noticed that, as well. Also, Matt Ridley is not a scientist. His 'doctorate' is in philosophy. He is actually the kind of person his article describes in negative terms.

And if we want to look for unabated and idiotic self-promotion, look no further the Oval Office.

It is available, and one doesn't need to be a subscriber to read it. BTW, the seeder copied/pasted the entire article verbatim.

Thank you.

Huh!?!

You're welcome, Vic. I, too, got an error 404 on your seeded link, but with less than a minute's effort by using key words, I easily found the article on my preferred search engine, DuckDuckGo.

The problem isn't the science itself, but rather those who seek to misrepresent science, most notably demonstrated by politicians and/or political influence. But scientists who do misrepresent science are probably a small minority. Science itself is still the best means to make discoveries and solve problems.

This one agrees with you:

....The underlying assumption of the blueprint is that race-based coronavirus disparities are the result of “systemic racism,” despite zero evidence that the state’s coronavirus policies have been discriminatory. The plan ignores potential differences in culture, behavior, and underlying health, resting instead on the premise that racism is the driving force behind every disparate outcome. The blueprint also subverts the democratic process. Unelected public health officials are restricting essential freedoms, including mobility, worship, and economic activity, without deliberation by the state legislature or the possibility of review or appeal.

Unfortunately, the California blueprint is just part of a broader pattern of state governments using public health as a rationale for seizing power. Throughout the pandemic, blue-state politicians have appealed to science as justification for long-term economic lockdowns, mask mandates, and other emergency measures, regardless of whether these policies have been sanctioned by state legislatures or voters. Science becomes the highest authority; citizens must obey.

Yet progressive leaders have been willing immediately to jettison science when it conflicts with their pre-existing political priorities. Earlier this summer, leading epidemiologists pilloried conservative lockdown protestors—declaring them a threat to public health—but then endorsed the much larger Black Lives Matter protests following the death of George Floyd in May. In short, they created a policy of “science for thee, but not for me.”

The disproportionate victims of any attempt to race-code the criteria for reopening in California will be the poor, the marginalized, and the nonwhite—the very people whom the equity policies are supposed to help. If, that is, Los Angeles County fails to reopen because it falls short of its “health equity metrics,” the Zoom class of intellectuals, public health officials, and progressive politicians will celebrate its own good intentions, even as bartenders, waitresses, taxi drivers, and small shopkeepers—many of them minorities—find themselves out of work.

The public should be on alert. If the progressive-scientific establishment can simply dictate policy outside the democratic process by appealing to “public health equity”—a vague concept that can extend to almost every facet of human life—voters may soon find themselves at the mercy of a new “ soft totalitarianism ,” as author Rod Dreher has characterized it. Citizens with a basic respect for freedom should resist this new encroachment. It degrades science, language, and democracy all at once, and acknowledges no natural limit to its power....

read more:

What exactly do you think is in agreement with me? As if a publication backed by the Discovery Institute actually means anything or has any real credibility. I assure you, it doesn't!

The ''seeded content'' is no longer there. It disappeared, like magic.

go figure, huh?

and Sister and devangelical ...

Please see comment 1.1.2 .

I wish more people understood this concept. Science is not about authority, celebrity, politics, religion or charisma. Science is about accurately explaining phenomena based on a formal discipline designed to mitigate human flaws. If an explanation explains the evidence then the explanation has merit, if not, it is discarded.

Scientists are not omniscient; they will provide the best explanations they can given the information at their disposal. The higher the quality of the information (evidence) the more likely to get a better explanation. Minimal information was available at the onset of the pandemic. Scientific opinion continues to converge as the information quality has improved.

Suppose we don't have enough masks during a pandemic?

Would they lie to the American people in order to discourage the rush to get masks, so that hospitals would have enough?

You didn't answer my question. It's about the integrity of scientists - the very ones calling the shots.

Then he lied about that too

They most certainly did. They killed the economy. It was Fauci's call.

You still can't answer why he lied?

How about basing everything off of IHME models and then telling us "You can't really rely on models?"

How about when he estimated that 1 million to 2 million Americans would die from coronavirus?

That one is not only forgotten, but buried by the media!

You either want the science or you don't?

You obviously can't answer the questions.

On January 21, the good doctor said it was unclear whether the virus could spread from person to person. Where did he get that from?

Vic, when are you going to cease repeating this one selective data point and flat out ignoring the rest of the picture (all the other data points)?

A single scientist operating as a spokesperson is not Science itself nor is he representing the collection of practicing scientists in the world. He (in this case, Fauci) is an individual with normal human failings and sometimes poor judgment.

Generalizing this as an attack on Science itself is a faulty generalization fallacy.

I gave you more than one data point.

A single scientist operating as a spokesperson is not Science itself nor is he representing the collection of practicing scientists in the world. He (in this case, Fauci) is an individual with normal human failings and sometimes poor judgment.

It's so nice to hear that, unfortunately this man really was the chief counsel on the coronavirus. We heard "follow the science" and it was followed. Because of the politics we can't even get anyone to admit that much, never mind how this man and the science were used by the media.

Generalizing this as an attack on Science itself is a faulty generalization fallacy.

That's a strawman argument. If you believe in "following the science", then - step 1 -you need to able to admit that "it" was followed.

This is your entire comment to me. One data point: lying about masks.

is your entire comment to me. One data point: lying about masks.

As I wrote:

Fault Fauci. Don't generalize the fault to Science itself or to all practicing scientists.

Then you do not understand what it means to make a strawman argument. I simply noted that your generalization is a logical fallacy:

What I stated is demonstrably correct. The failing of a single scientist (regardless of position) is not ipso facto a failing of Science nor is it a failing of all scientists. You are generalizing and the conclusion you are pushing is fallacious (wrong).

In the early months of the pandemic the administration did take care of the front-line workers first and even Fauci admitted that the Administration had followed his departments recommendations quite closely. I think what Vic is asking is why did Fauci, as a scientist, actually downplay the use of masks at that time rather than suggesting the bandanas be worn as you noted now in hindsight? I think that is a reasonable question as the medical community has worn face coverings for a very long time to protect themselves and their patients from bacterial and viral infection.

Having said that, I agree with TiG that scientists will adapt their conclusions as more data is gathered and more information becomes available. That is the nature of science. It isn't logical to assume that scientific opinion on a given subject won't change as more is learned. If the conclusions/opinions remained the same after more is learned, it wouldn't be science.

What we see more often are scientific opinions being bent for political purposes by politicians, pundits, and the media. We see scientists berated for their changing opinions over time (which is of course their job), for the purposes of now discounting their latest opinions. We see politicians using bits and pieces of the scientific findings (not necessarily the conclusions) to scare people or assign blame to their opponents when in fact the situation is fluid and multi-faceted. We see some politicians downplaying the science claiming to be concerned about unnecessary panic. We see other politicians and the media playing up the worst case scenarios/hypothesis while at the same time delivering a pass to those gathering in large numbers in close proximity, with and without masks, shouting, screaming, and expelling virus spreading droplets in the way that most scientists agree is possibly the worst case scenario. Those politicians and the media claiming the mantle of a higher cause over that of true science. Don't blame science! Blame what we as politicians, the media, and the average citizens do with the science. THAT is the problem, and always has been. Ask Oppenheimer....

Wow - I got interrupted so many times while writing this that 8 more comments popped up in the meantime. Anyway, TiG pointed out one other thing that we sometimes tend to do with scientific opinion or scientists, and that is to assume that they are infallible or aren't prone to the pressures of their jobs or positions. They are human just like the rest of us. But the mis-statements, errors, omissions or little white lies of one scientist do not warrant the mis-trust of science or the scientific method as a whole.

So you don't read anything else on the page? Just what is posted to you?

Fault Fauci. Don't generalize the fault to Science itself or to all practicing scientists.

That is not the argument I am making.

Then you do not understand what it means to make a strawman argument. I simply noted that your generalization is a logical fallacy:

No, you ignored my argument.

The failing of a single scientist (regardless of position) is not ipso facto a failing of Science nor is it a failing of all scientists.

I agreed to that point way back in post 3.1.9

Anyone else able to answer my questions or willing to admit that Fauci's advice was followed?

I replied to your comment @3.1 (the one where you replied to my comment @3). In my reply I noted your single data point. Your reply has one and only one data point. You have stated this singular data point to me multiple times in various articles. Thus I asked when you are going to move past this very dated, single data point.

Okay, then state your point as you would have me understand it.

And then after that, others ... including our leading doctors and politicians ... said that cruises, movie theaters, concerts, and large groups (in "peaceful protests") were safe. Until they decided to lock down the entire economy and told us to "shelter in place" for months ... maybe years.

This is a good point. Even Fauci admitted that Trump had followed all the recommendations in the first several months, but yet now the media and his detractors are bent on blaming Trump for all 250,000 deaths that have occurred due to Covid-19. Hell it is part of their campaign slogans now. Not to mention the fact that the policies that should be based on the best available science in terms of slowing the spread of this virus are set by state governors/legislatures, not the Federal Government.

Yes, it's a shame the way science was used and politicized. I think the point has been made and we can end it there.

We have learned that anything can be said about Trump and yup, he got the blame for all the deaths.

Not to mention the fact that the policies that should be based on the best available science in terms of slowing the spread of this virus are set by state governors/legislatures, not the Federal Government.

That deserves an article of it's own.

It's taught us that many people are downright ignorant of science, if not outright hostile towards it. Possibly because people prefer something more emotionally comforting or less disruptive to their status quo. But when scientists produce an effective vaccine to Covid and other demonstrated means to halting the pandemic, science will teach us that there is nothing better suited to making discoveries and finding solutions to problems than science itself. Assuming people are actually open to learning that particular lesson. Unfortunately, some prefer to remain willfully ignorant.

Indeed. But it has also taught us that some people will claim to be champions of science, yet then be perfectly willing to ignore it for political gain, or at least to score political points that could have been scored in a number of less dangerous ways.

No doubt, and we can see that. Especially from politicians. It's just another form of political pandering, like we see with politicians trying to suck up to a religious base.

Dr. Fauci isn't running for political office nor is he a politician. He is a scientist first and foremost. But he is in the unenviable position of trying to tiptoe the line between science and politics and advise less scientifically minded politicians.